|

|

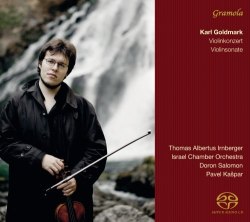

Karl GOLDMARK (1830-1915)

Violin Concerto in A minor, Op.28 (1877) [34:27]

Violin Sonata in D major, Op.25 (1874) [38:09]

Thomas Albertus Irnberger (violin)

Israel Chamber Orchestra/Doron Salomon

Pavel Kašpar (piano)

rec. November 2012, Ted and Lin Arison Conservatory of Music, Tel Aviv (Concerto) and February 2013 at Mozartsaal, Salzburg (Sonata)

GRAMOLA 98986  [72:38] [72:38]

There was a long vogue for Goldmark’s Violin Concerto but it was largely restricted to the second movement. Sitting by the fireside, with your trusty gramophone playing, the chances are that you’d be listening to a 78 played by the likes of Heifetz, Příhoda, Catterall or Chemet, or other Titans of the recorded industry. Even Arnold Rosé himself, doyen of Viennese fiddlers, recorded a bit of the first and second movements. So it wasn’t just Milstein who trail-blazed this concerto into the consciousness of the listening public through his LP recording with Harry Blech. No one could live without that recording. Still, Joshua Bell, Sarah Chang, Ruggiero Ricci and Itzhak Perlman have all recorded it over the last two decades or so and each has brought real insights to bear.

The latest performer is the young fiddler Thomas Albertus Irnberger, Salzburg-born and a pupil of Ivry Gitlis. Doron Salomon directs the Israel Chamber Orchestra in a SACD recording that is mellow but slightly shallow. I wonder if more strings would have beefed up the sound. Still, I must note that the performance concentrates on the many felicities and beauties in Goldmark’s score and that Irnberger plays at all times with great purity and elegance. His relaxed refinement suits the inward-looking moments of the first movement and the whole of the slow one very well. It’s a performance of quiet beauty, with much rapt phrasing. In the finale one feels him opening up more, bowing just a touch harder, revealing an excellent spiccato and deploying a few near-resinous attacks. However the gift of the playing is an elevated nobility of spirit. The other violinists cited earlier combine rather more overt flair with a bigger orchestral patina. For those who want to savour the silvery expressivity of the writing there is much to enjoy here. It’s not necessarily crude to point out that Goldmark was, or believed himself to be, quite the ladies’ man. It’s that kind of concerto.

A few years earlier he had written a Violin Sonata. At 38 minutes in this performance it’s a big work, and not one that escapes the charge of over-extension. That said, the dappled piano writing of the first movement and the musing introspection of the violin writing are the obverse of extroversion. There are some gorgeous upward-ascending fiddle phrases in the central slow movement and a typically Goldmarkian mix of fast and more reflective contrastive material in the finale. This is a much less successful work than the Concerto and the relatively few recordings it’s received strongly makes the point. Pianist Pavel Kašpar plays as well as Irnberger here. Some might know Kašpar from his Martinů recordings on Tudor.

If it’s Goldmark the violin purveyor, pure and simple, that you want then these sensitive and thoughtful performances are persuasively successful, though for more consistently nonchalant advocacy you may need to search further afield.

Jonathan Woolf

|

|

|