|

|

Support us

financially by purchasing this disc from

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

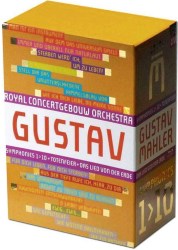

Gustav MAHLER (1860-1911)

Symphonies 1-10, Totenfeier, Das Lied von der Erde

see end of review for detailed listings

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Daniel Harding, Mariss Jansons, Iván

Fischer, Daniele Gatti, Lorin Maazel, Pierre Boulez, Bernard Haitink,

Eliahu Inbal, Fabio Luisi

rec. live, 2009-2011, Concertgebouw, Amsterdam

Video directors: Hans Hulscher, Joost Honselaar

Picture: 1080i Full HD

Sound: PCM Stereo, dts-HD Master Audio Surround

No liner-notes or credits/subtitles

RCO LIVE RCO12102  BLU-RAY BLU-RAY

[11 discs: 14:22:00]

Founded in 1888 Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra has

had a long and distinguished relationship with the music of Gustav

Mahler. Chief conductor Willem Mengelberg first met the composer in

1902 and invited him to give the Dutch premieres of several of his

symphonies. By all accounts it was a close and fruitful relationship,

and one that set in train more than a century of ground-breaking Mahler

performances; there was the famous Mahler Festival of 1920, and after

Mengelberg’s controversial downfall in 1945 it was left to Eduard

van Beinum and Bernard Haitink - chief conductors from 1945 to 1959

and 1961 to 1988 respectively - to continue this fine tradition.

Since then the Concertgebouw has been led by a number of notable Mahlerians,

Riccardo Chailly - their chief conductor from 1988 to 2004 - among

them. As for Haitink’s 1960s Mahler recordings they’re

pioneering efforts and must be celebrated; Chailly’s Decca box

is more variable, although he has since made amends with a splendid

Gewandhaus Resurrection on Blu-ray/DVD (review).

Mariss Jansons, the orchestra’s chief conductor since 2004,

has yet to persuade me of his Mahlerian credentials. Yes, he has directed

a very good Second in Oslo (Chandos) but his more recent SACDs for

RCO Live don’t always challenge the best in the catalogue.

The real selling point of these handsomely packaged and funkily designed

RCO Live Blu-rays and DVDs is that the symphonies are farmed out to

several conductors. Jansons has the plums - the Second, Third and

Eighth - while the rest are taken by baton-wavers with at least something

of a track record in Mahler. Daniel Harding’s Vienna Mahler

Tenth for DG certainly impressed Anne Ozorio (review)

and Daniele Gatti has recorded a much-lauded Fifth for Conifer. Eliahu

Inbal, Lorin Maazel and Pierre Boulez need no introduction when it

comes to this repertoire, although Fabio Luisi is only known to me

for his incomplete Strauss cycle for Sony. Surprisingly, the latter

gets two bites of the cherry, with performances of Totenfeier

- the basis for the first movement of the Second symphony - and Das

Lied von der Erde.

Actually this set has another advantage; at the time of writing it’s

the only complete Mahler cycle on Blu-ray. Claudio Abbado’s

Lucerne performances are split between Euroarts and Accentus; Euroarts’

box of the first seven symphonies and the Rückert Lieder

- individual issues were blighted by technical problems - was well

received by Dave Billinge (review).

The Accentus Ninth has since appeared separately, with the Eighth

and Das Lied von der Erde still awaited. As Abbado has never

embraced Deryck Cooke’s - or anyone else’s - performing

version of the Tenth all we can expect from him is the usual stand-alone

Adagio.

As it happens, Harding - who conducts the First symphony -

was hired as Abbado’s assistant at the Berliner Philharmoniker

after holding a similar post with Simon Rattle and the CBSO. He is

also music director of the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, formed in 1997

by Abbado and a group of musicians from the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra.

All of which augurs well for this opening concert, as does the ear-pricking

loveliness at the start. Harding, with score but sans baton,

has a florid style of conducting that, alas, soon manifests itself

in a very beautiful but somewhat mannered reading of this symphony.

Articulation is not terribly crisp and, like compatriot Jonathan Nott

in the same work, Harding has an irritating habit of parenthesising

phrases. By contrast, Klaus Tennstedt - in his live BBC Legends recording

- finds a seamless urgency here that translates into a uniquely gripping

performance (review).

Harding is just too self-indulgent, with the result that momentum

falters and ensemble is often less than tidy. The delectable Ländler

in the second movement aren’t very well sprung either, and that

ghostly Frère Jacques tune in the third is curiously

po-faced. As for the finale it’s just too fitful; and while

climaxes are undeniably thrilling the lack of structural cohesion

and cumulative tension makes for a very unconvincing performance.

Despite all those promising signs this is an underwhelming First.

On this occasion at least Harding doesn’t have a penetrating

view of this piece; like Narcissus gazing into the pool, he seems

mesmerised by its outward beauty rather than fully engaged with its

inner shifts and subtleties. I suppose one could characterise this

as a generalised reading, whose lack of shape and focus isn’t

helped by some hesitant camerawork and a tubby sound familiar from

some of RCO Live’s SACDs. On the evidence of this performance

- greeted with enthusiasm in the hall by the way - I can understand

why Harding is a polarising figure; that said, he’s only in

his 30s, so perhaps his best Mahler is yet to come.

Jansons’ performance of the Second symphony - which uses

an edition by Austrian musicologist Renate Stark-Voit and Mahler conductor/devotee

Gilbert Kaplan - is everything Harding’s First is not. He directs

a taut, nicely scaled reading of the first movement; tempo relationships

are well judged, the playing combines refinement with terrific attack

and, perhaps most important, there’s a strong feeling that Jansons

understands the work’s architecture. The burnished woodwinds

and silken strings are simply gorgeous, and the bass drum has enormous

impact in those eruptive tuttis.

The precision and point of the Ländler-driven Andante

is a joy to hear; the orchestra sound supremely elegant, and they

play with a breath-taking transparency that brings out every nudge

and nuance of this miraculous score. In the past I’ve felt Jansons

micro-manages too much, which gets in the way of spontaneity and lift.

That certainly isn’t the case here; indeed, I’d say this

must be one of the loveliest, most naturally phrased accounts of this

movement I’ve heard in a long time. The weird, wall-eyed Scherzo

is no less engaging; rhythms are always supple and that pivotal trumpet-

and harp-led tune sings out most beautifully.

In the presence of such unwavering musicianship one is inclined to

agree with those Gramophone critics who declared the Concertgebouw

the finest orchestra in the world. As for mezzo Bernarda Fink she

gives a radiant account of ‘Urlicht’, although diction

is sacrificed to her pure, seamless line. The long, taxing finale

is unerringly paced and Jansons ensures it builds implacably to a

light-drenched close. The off-stage brass are suitably distant and

the choirs sing well, albeit with a rather soft grain. I was a little

disconcerted by what sounds like unguarded vocalising from the conductor

at the first appearance of the Resurrection motif and early in ‘O

glaube’. Minor quibbles really. Jansons’ Mahler 2 isn’t

as consistently satisfying - or as sumptuously recorded - as Chailly’s

from Leipzig, but it’s still a very compelling account. See

also David McConnell’s review

of the Unitel DVD.

For many Abbado leads the field in Mahler’s Third symphony;

on CD his Vienna and Berlin performances are long-time favourites

of mine, and his Lucerne Blu-ray/DVD doesn’t disappoint either.

Now rustic, now lofty, inward and exultant, this sprawling work reveals

Mahler at his genial, open-hearted best; the highly disciplined start

to Jansons’ account - a brace of horns to the fore - captures

the exuberance of the piece, but the downside is that such precision

robs the music of much of its bucolic charm. Also, those accustomed

to the easy efflorescence of Abbado’s performances may find

Jansons’ fractional hesitations a tad off-putting.

The playing is superb and the dynamics of this recording are very

impressive, but try as I might I just could not engage with Jansons’

curiously under-characterised reading of the first movement. Kräftig,

Entschieden it most certainly is, but where is the light and shade,

the sharp wit and grinning parody? As for the Tempo di Menuetto

it does dance, albeit with stiff joints. Such rhythmic inflexibility

and a tendency to swoop and swoon are not what this fleeting, diaphanous

music needs; true, the RCO give us a masterclass in orchestral virtuosity,

but that’s simply not enough.

The Scherzo is problematic too; the posthorn is very distant,

and instead of agogic pauses Jansons encourages a self-indulgent,

soupy sound that doesn’t appeal to me at all. One only has to

listen to Abbado to hear how a ‘straight’, unsentimental

approach brings out the hushed intensity of this wistful dialogue.

As expected, Jansons’ troops respond to those crunching tuttis

with all the ferocity they can muster. Jansons also emphasises the

martial quality of much of Mahler’s brass writing, to thrilling

effect. What a pity there aren’t more of these telling touches,

which could so easily turn a good performance into a great one.

Bernarda Fink’s ‘O Mensch!’ is beautifully sung,

although her soft-edged delivery masks her consonants. As for Jansons,

he verges on expressive overload here; this tends to happen when Mahler’s

scoring is at its most transparent and demands the lightest touch.

That said, the choirs sing well enough, but some may feel that Jansons

exaggerates the dynamics somewhat. Indeed, the recording is a little

too ‘hi-fi’ at times - the bass drum has an overpowering,

Telarc-like presence - and perspectives aren’t always entirely

natural. Still, I doubt that matters too much in the light of such

committed playing.

The long, unfurling finale can make or break a performance of the

Third. It doesn’t in this case; Abbado may sustain the natural

rise and fall of this movement better than most, but from that mighty

cymbal clash onwards Jansons and the RCO unleash an exultant surge

of sound that’s as hair-raising as you’ll hear anywhere.

What a splendid end to an otherwise uneven performance. Given that

Jansons and his Dutch band have such a remarkable rapport - they play

for him with a unanimity and passion that I don’t hear with

Harding - it seems almost perverse to grumble about this detail or

that. But that’s what reviewers do; so while Jansons’

Mahler 3 has its moments it doesn’t really rival the best in

the catalogue, either on audio or video.

Iván Fischer, the Budapest Festival Orchestra and Miah Persson

featured in an SACD of Mahler’s Fourth symphony that

Leslie Wright claims ‘is the one to beat’ (review).

As I’ve not warmed to Fischer’s Mahler thus far I wondered

if this live RCO account would make a difference. The first movement,

very well paced and articulated, has wit and warmth, and its contrasting

sections dovetail most beautifully. Fischer, sans score, clearly

has the measure of this effervescent work; indeed, he reveals a range

of subtle colours and sonorities in the gorgeous, sun-dappled opening

scene that one rarely hears in the concert hall, let alone in a recording.

The Scherzo is lithe and lovely, and Death’s Fiddle sounds

more beguiling than ever. It’s a strange mix, to which the punctuating

horn adds a plaintive charm. Fischer is extraordinarily communicative,

and his expressive eyes and hands make plain what he wants from his

players. He allows himself a little smile after that genial and uplifting

display; in turn, the RCO seem intent on rediscovering the delights

of this oft-played score. The third movement is a model of natural

phrasing and fine dynamic control; the orchestra play with rapt intensity,

their unguarded expressions of wonderment ample proof that this is

a performance of unusual insight and stature.

Can it get any better? Oh, yes. My first reaction to Miah Persson

in the child-heaven finale was consonants at last! Her winning blend

of accuracy, animation and essential artlessness makes for an ideal

rendition of this Wunderhorn song. Goodness, the sheer dynamism of

her singing makes many of her rivals seem sphinx-like. Fischer, alert

as ever, coaxes radiant sounds from his players. This is music of

pure innocence, and I have never heard it so beautifully done. The

profound spell is left to linger at the close, before being broken

by a storm of applause and roars of approbation. This inspired and

deeply moving account of the Fourth must surely rank high on the list

of transcendent Mahler performances heard in this hall over the past

100 years. Yes, it really is that good.

After a paradigm-shifting Fourth comes an earth-shaking Fifth.

From its terrifying, seismic first bars Daniele Gatti and the RCO

give a trenchant and propulsive account of this forbidding symphony.

This Trauermarsch is every bit as gripping as Abbado’s

(review),

and its moments of inwardness and illumination are as cosseting as

the big tuttis are fearsome. Gatti’s is a hard-driven Fifth,

yet remarkably the first two movements never seem unremittingly so.

The engineers have surpassed themselves too, capturing the thrill

of this great orchestra in full flood.

Anyone hoping for some light relief in the Scherzo will be

disappointed, for Gatti is in no mood for levity. Indeed, the wells

of darkness here are bottomless, and I can’t remember being

so profoundly disturbed by this music as I was here. The RCO never

let up either; in that sense they’re very much like the Lucerners,

whose playing for Abbado in this symphony is almost superhuman. As

for Gatti’s Adagietto, it couldn’t be further from

a dewy-eyed interlude. Darkly eloquent - stoic even - Gatti’s

view of this love music is as unsentimental as it could possibly be

without ever seeming curt or dismissive.

Gatti doesn’t dawdle in the Rondo-Finale either, and

while Abbado is more spacious both leave one gasping at the close.

If anything Gatti slams the door on this symphony more emphatically

than most. As with Fischer’s Fourth, the applause is enthusiastic.

Theirs may be two very different performances, but they have one thing

in common: in an age of numbing ubiquity they offer thoughtful and

very individual takes on these oft-played scores.

The Sixth symphony is conducted by Lorin Maazel, a maestro

who often gets tepid reviews from critics - on this side of the Atlantic

at least. I have positive memories of his Royal Albert Hall Mahler

8 from about 1980, and his Blu-ray of Wagner’s Ring without

words evinces a sure grasp of large structures and a good ear

for orchestral balance, both essential in Mahler. Older readers will

remember his CBS Mahler cycle, which yielded a particularly fine Fourth.

And for those who fret about these things, he opts for Scherzo - Andante

in the Sixth.

For a conductor who’s often accused of being aloof Maazel finds

a warmth - what some might call a humanity - in the first movement

of this Sixth that reminds me so much of Abbado’s Chicago recording

for DG. Those repeated rhythms - apt to chug - are nicely done, and

Maazel shapes the music well. That said, he’s not as characterful

as some - Pierre Boulez and the Wiener Philharmoniker on DG are peerless

in this regard - although that’s hardly a deal-breaker when

so much else goes right. As ever, the RCO sound utterly committed,

and the recording is as good as anything I’ve heard thus far.

Maazel’s Scherzo is rather subdued, and its curious low

and bleat is underplayed. Ditto those Altväterisch episodes.

Rhythms aren’t always that supple either, and while this is

a perfectly decent performance it sounds a tad routine at times. I

also had some misgivings about the plush Andante which, although

it has a strong pulse, has a rather soft edge. Still, Maazel builds

tension superbly and he gives the music terrific sweep later on. It’s

also good to actually hear the celesta playing its part at

the ear-pricking close. Perhaps most important, the movement ends

on tenterhooks, and that sharpens the sense of impending cataclysm

- and makes a good case for placing the Andante just before

the Finale.

There’s certainly an expectant buzz in the hall at this point,

a mental tightening of seat belts as it were ... and what a ride it

is. Normally urbane and unflappable, Maazel gives a hugely theatrical

reading of the last movement that leaves one emotionally spent; and

that’s as it should be, for this is one of the most wrenching

finales in all Mahler. That sense of theatre extends to the hammer-blows

- two of them - the mallet in the second rising like an executioner’s

axe before it falls. As with Fischer’s Fourth, one senses the

orchestra are gripped by the titanic drama unfolding around them.

The audience - who appear to hold this octogenerian conductor in high

esteem - respond with thunderous applause; and that’s also as

it should be, for if this were Maazel’s last performance on

earth it would be a splendid send-off. Bravo, maestro!

After a pause to collect my thoughts and regain my composure I plunged

straight into Pierre Boulez’s account of the Seventh

symphony. Critics and collectors are divided about the virtues of

his CBS and DG Mahler recordings, although that unforgettable WP Sixth

is probably one of the best things he’s ever done - period.

I was much less impressed by his DG Seventh, so I hoped he would atone

for that with this RCO Live performance. First impressions aren’t

entirely favourable, as Boulez directs an ultra-lucid reading of the

first movement; textures are clarified, rhythms are razor-sharp and

leading edges are strongly defined. It’s so terribly metrical

- almost dogged - and I don’t sense either the unsmiling maestro

or his players are having a good time.

Alas, this is Boulez at his most detached and dispiriting; no it isn’t

Notations, it’s Mahler, and a more yielding, less didactic

approach wouldn’t go amiss here. As for the things-that-go-bump-in-the-nacht

they’re humourless as well. I can’t recall a less communicative

account of this quirky, elliptical score; the Scherzo simply

refuses to gel and I longed for the affection and bounce that Abbado

and his Lucerne players find in this music (review).

As if that weren’t disappointment enough Boulez gives us a finale

of unimaginable dreariness. Eyes on the score he looks as if he’d

rather be somewhere else; frankly, if I were in the audience I’d

have wished the same. Simply dreadful.

Jansons returns with the Eighth symphony; of the two versions

I’ve seen on Blu-ray - from Chailly and Dudamel - the latter’s

Bolivar/LAPO account is by far the more successful (review).

Well controlled yet brimming with vitality it’s a performance

that confirms Dudamel as a fast-maturing maestro whose charisma and

talent might just take him to Berlin in 2018. Back to the present,

and loading the Jansons disc I realised - belatedly - that these RCO

Blu-rays have no subtitles. Really, that’s a lamentable oversight

which, added to the lack of printed notes, is surprising in a premium-priced

product such as this.

What of the performance though? Vocally it’s a strong cast,

and seeing all those choirs, players and soloists on the stage certainly

sets the pulse racing. Seconds into the opening hymn and it’s

clear this is going to be an Eighth to remember. The organ is powerful

without being overwhelming, the choruses are transported in the big

tuttis and Jansons brings a thrust and urgency to the proceedings

that I haven’t heard since Solti. Goodness, this is a fine performance,

and I defy you not to be swept along by this mighty maelstrom. The

well-matched soloists - dominated by the familiar tones of Christine

Brewer and the unfamiliar but commanding ones of Stefan Kocán

- are generally excellent; as for the huge dynamic swings of Part

I they’re captured in sound of considerable weight and splendour.

The promising buds of Jansons’ RCO Second bloom most beautifully

in the Eighth; nowhere is that more evident than in the myth-laden

landscapes of Part II. He paces the music consistently - no odd pauses

- and he allows it to breathe; also, there’s a warm glow to

the playing that can’t fail to please. Longueurs there

are none, and the soloists - with the exception of tenor Robert Dean

Smith - are very robust indeed. The clear, crisp singing of the choirs

is particularly welcome, and the closing minutes of this performance

are stupendous. Despite a brief wobble in the final seconds - a rare

lapse of concentration, perhaps - the organ is very convincing. The

rapturous reception and standing ovation are richly deserved, but

it’s Jansons’ return to the podium that really raises

the roof.

Given Bernard Haitink’s role in the Mahler renaissance that

took hold in the 1960s it’s entirely right that he conducts

this crowning Ninth. I must confess, though, that for all his

advocacy and manifold strengths in this music I never quite understood

why his Philips recording of the Ninth was so highly regarded. For

me at least there are many fine versions that dig deeper, and do justice

to this complex and profoundly moving work. Perhaps age - mine, not

Haitink’s - and the palpable sense of occasion afforded by this

RCO concert would make all the difference.

There are few composers as nakedly autobiographical in their music

as Mahler, but even then I’m cautious about reading too much

into the notes. That said, there’s little doubt the Ninth is

a life distilled, a procession of rememberings and regrets played

out in score of aching loveliness and quiet introspection. Alongside

Bernstein - in his last and most extreme account on DG - Haitink is

plainer and more purposeful. There are no added histrionics, and that

allows the symphony to unfold with a simple eloquence that’s

deeply affecting. Indeed, the systolic beats of the timps, the stopp’d

trombones and those wistful horns in the Andante comodo

have a poignancy I don’t remember from Haitink’s Philips

disc.

This is a Mahler Ninth - like Haitink’s LSO Alpensinfonie

- viewed from the summit of a long and distinguished conducting career.

It needs no gimmicks or intervention, and a more revelatory account

of the second movement would be hard to imagine. In the face of tribulations

to come these trills speak of ease and contentment; the RCO play with

fabulous poise and point, adding to a powerful sense of reawakening

and rediscovery. It’s remarkable that even after all these years

this and the music of the Rondo-Burleske can still sound newly

minted; that’s rare - and most welcome - in a crowded and all-too-unvarying

field of Mahler 9s. In that respect this performance is a perfect

companion for the Fischer Fourth.

Nothing quite prepared me for Haitink’s view of the long, dissolving

finale; measured but never self-indulgent, despairing but not hysterical,

this Adagio ebbs and flows most beautifully. The orchestral

blend is as close to perfection as you’ll ever hear, and the

recording’s refulgent bass lowers the music’s centre of

gravity to telling effect; indeed, it’s an unforgettable sound

that brings to mind Sergiu Celibidache’s unique way with Bruckner.

As for the many epiphanies of this valedictory movement each and every

one is indescribably moving. At the end Haitink acknowledges a deep-ocean

swell of applause and affection. Typically self-effacing, he calls

on individual players to take a bow as well.

As superlative as Fischer’s Fourth is, this Ninth is in another

realm entirely. I doubt the RCO’s ageing conductor laureate

will ever frame a more authoritative account of this great work -

and it’s all captured in superb sound as well. Quite simply

this is the most complete and compelling performance of Mahler’s

Ninth I’ve ever encountered, as much a tribute to s great orchestra

as it is to a most distinguished and much-loved maestro.

An ‘almost is’ or a ‘never was’, whatever

one’s view of the Tenth it can - and often does - work

very well in the right hands. Simon Rattle’s Bournemouth and

Berlin recordings - both of which use Deryck Cooke’s completion

- are indispensable additions to the Mahler discography. I found Mark

Wigglesworth’s recent Melbourne CD somewhat variable - review

- but as far as I’m aware this RCO/Eliahu Inbal account is the

only Cooke Tenth on Blu-ray. That said, there’s a performance

of the Clinton Carpenter completion from Lan Shui and the admirable

Singapore Symphony on Avie. As for the professorial Inbal, I remember

what could have been a decent Mahler 2 at a City of London Festival

some years ago; sadly the cavernous acoustics of St Paul’s did

for the performance as surely as a stiletto between the ribs.

The Adagio of this Tenth goes quite well; Inbal is perhaps

more lyrical than intense, although those trumpet-topp’d tuttis

are mighty indeed. The recording copes well with these dynamic extremes,

and the sometimes gossamer-light string writing is especially well

caught. It’s only in the first Scherzo that the doubts

begin to surface; as much as I admire Cooke’s realisation of

Mahler’s sketches I find textures can sound threadbare, and

there are ill-concealed gear changes too. Perhaps it’s a result

of listening to all the symphonies and coming to this Tenth right

after the micrometer calibrations of Haitink’s Ninth that makes

the former sound somewhat rough and ready.

Then again Rattle is much more convincing in terms of echt-Mahlerian

sonorities and thrust than Inbal, so it’s not just about the

score. One has to remember Cooke’s is a ‘performing version’

and that means the conductor has to make far more interpretive decisions

than might otherwise be the case. That said, I find Inbal much to

brisk - and not a little brash - in the Purgatorio, whose many

seams are apt to gape. After the sheer discipline shown in the earlier

symphonies the RCO aren’t at their unanimous and sophisticated

best, either.

Alas, it doesn’t get any better; the second Scherzo grates

and even the dark elegy that is the Finale - complete with

dramatic drum thuds - is much less affecting than usual. Suffice to

say, if this performance were my introduction to Cooke’s - or

anyone else’s - Mahler I’d not be persuaded. Along with

the Harding First and Boulez’s Seventh this uneven and untidy

Tenth is eminently forgettable.

As Fabio Luisi doesn’t appear to have much of a history with

Mahler - on record at least - his Totenfeier

and Das Lied von der Erde are the wild cards in the

set. The former, a symphonic poem later reworked into the first movement

of the Second symphony, is a rare and entertaining oddity lasting

some 20 minutes. Unsuspecting listeners might think they’d stumbled

across an extremely brisk performance of the Resurrection;

in the event Totenfeier is an intriguing glimpse of a work

in progress. The skeleton is recognisable, but it’s fascinating

to hear how Mahler eventually fleshed it all out; even more instructive

is noting how sometimes small changes of scoring and dynamics transformed

this uneven fragment into its final, definitive shape.

On to Das Lied von der Erde, which opens with an impetuous

and none-too-subtle account of the drinking song. One can only sympathise

with Robert Dean Smith; not only does he have to deal with Mahler’s

taxing tessitura but he also has to struggle to make himself heard

above the orchestra. That said, his voice isn’t particularly

robust or distinctive, and there are audible - and visible - signs

that he’s not too comfortable here. As for Luisi, he has a jittery

podium manner that I find very distracting; also he wields his baton

like a rapier, bringing the song to a close with a murderous thrust.

This work really underlines the need for subtitles, as not all viewers

will be familiar with either the song titles or texts. The lack of

liner-notes means they don’t have printed versions to fall back

on either; unforgivable omissions on both counts. Back to the music,

and Anna Larsson, a seasoned Mahlerian, gives a strong if not very

insightful performance of Der Einsame im Herbst. Perhaps she’s

not always as secure as she once was, but she certainly has a pretty

good idea of how this song should go. I have misgivings about Luisi

though; he’s competent enough, but I don’t warm to his

Mahler ‘sound’ and I find him a tad anonymous at times.

Sadly, the same goes for our tenor in Von der Jugend; he still

doesn’t look or sound at ease, and the orchestral accompaniment

is woefully short on atmosphere. Larsson is just fine in Von der

Schönheit, although I sense Luisi isn’t listening to

his singers very carefully; indeed, there are times when it seems

soloist and conductor are working to a slightly different beat. Smith’s

pinched upper registers are even more apparent in Der Trunkene

im Frühling, and his lower ones aren’t very warm or

rounded either.

Larsson delivers an eloquent farewell, despite Luisi’s somewhat

mannered phrasing and odd rhythms. Generally I find this performance

- like the Harding First - too self-consciously ‘interpreted’.

In the most illuminating concerts - Fischer’s and Haitink’s

- the conductor seems to melt away and we come much closer to what

the composer intended. On the strength of this Das Lied von der

Erde I’m not at all convinced that Luisi is a front runner

in this repertoire. It’s a real pity that this otherwise splendid

set should conclude with such a disappointing disc.

So, if you want all the Mahler symphonies on Blu-ray and conveniently

packaged this RCO box is your only choice. If they were available

separately I’d happily acquire the stand-out performances -

Fischer’s Fourth, Gatti’s Fifth, Maazel’s Sixth,

Jansons’ Eighth and Haitink’s Ninth - and that would be

pricier than the entire set. That said, there are aspects of presentation

that need to be addressed. I’ve already grumbled about the lack

of on-screen captions, credits and subtitles, but I have to say the

visuals leave something to be desired as well. The pictures are sharp

and the colours are true, but there are some jerky pans and ill-judged

close-ups that are very distracting. Also, in some of the concerts

the applause ends rather abruptly, with no attempt at a clean or elegant

fade. Finally, framing is an issue at times, with weird, disembodied

shots of conductors’ arms and hands; the effect is disconcerting,

and it looks very amateurish.

Dan Morgan

http://twitter.com/mahlerei

A very decent survey, with some top-notch performances; presentational

issues are a let-down though.

Masterwork Index: Mahler symphonies

Detailed listings

Symphony No. 1 in D major (1884-1888, rev. 1906) [60:00]

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Daniel Harding

rec. 30 September 2009

Symphony No. 2 in C minor Resurrection (1888-1894; revised

edition by Renate Stark-Voit & Gilbert Kaplan) [90:00]

Ricarda Merbeth (soprano)

Bernarda Fink (mezzo)

Netherlands Radio Choir

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Mariss Jansons

rec. 3 December 2009

Symphony No. 3 in D minor (1893-1896, rev. 1906, K. H. Füssl

Edition) [103:00]

Bernarda Fink (mezzo)

Netherlands Radio Choir

Boys of the Breda Sacrament Choir

Rijnmond Boys Choir

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Mariss Jansons

rec. 3-4 February 2010

Symphony No. 4 in G major (1899-1900) [61:00]

Miah Persson (soprano)

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Iván Fischer

rec. 22-23 April 2010

Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor (1901-1902) [76:00]

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Daniele Gatti

rec. 25 June 2010

Symphony No. 6 in A minor Tragic (1903-1904, rev. 1906) [79:00]

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Lorin Maazel

rec. 20 October 2010

Symphony No. 7 in E minor (1904-1905) [80:00]

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Pierre Boulez

rec. 20-21 January 2011

Symphony No. 8 in E flat major Symphony of a Thousand (1906)

[87:00]

Una poenitentium - Camilla Nylund (soprano)

Magna peccatrix - Christine Brewer (soprano)

Mater gloriosa - Maria Espada (soprano)

Mulier samaritana - Stephanie Blythe (alto I)

Maria aegyptiaca - Mihoko Fujimura (alto II)

Doctor marianus - Robert Dean Smith (tenor)

Pater ecstaticus - Tommi Hakala (baritone)

Pater profundus - Stefan Kocán (bass)

Bavarian Radio Chorus, Netherlands Radio Choir, Latvian State Choir,

National Children’s Choir, National Children’s Choir (Junior)

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Mariss Jansons

rec. 4 & 6 March 2011

Symphony No. 9 in D major (1908-1909) [93:00]

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Bernard Haitink

rec. 13 & 15 May 2011

Symphony No. 10 in F sharp minor/major (1910) (ed. Deryck Cooke) [77:00]

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Eliahu Inbal

rec. 30 June 2011

Totenfeier (1888) [25:00]

Das Lied von der Erde (1908-1909)* [68:00]

*Anna Larsson (alto)

*Robert Dean Smith (tenor)

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Fabio Luisi

rec. 18 & 20 May 2011

|