|

|

Support us

financially by purchasing this disc from

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

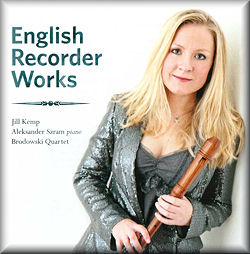

English Recorder Works

Lennox BERKELEY (1903-1989) Sonatina Op.13 (1939) [9:38]

Malcolm ARNOLD (1921-2006) Sonatina Op.41 (1953) [7:39]

Gordon JACOB (1895-1984) Suite for Recorder and String

Quartet (1957) [20:28]

Malcolm ARNOLD Solitaire (1956) [1:35]

York BOWEN (1884-1961) Sonata Op.121 (1946) [12:19]

Edmund RUBBRA (1901-1986) Meditation sopra ‘Coeurs Désolés’

(1949) [5:47]

Malcolm ARNOLD Fantasy for Recorder and String Quartet, Op.140

(1990) [13:46]

Jill Kemp (recorder)

Aleksander Szram (piano) Brodowski Quartet

Rec. Potton Hall, Suffolk, 4-6 September 2010

MUSIC MEDIA MMC103 [70:58]

Whenever reviewing a CD of recorder music, I have to hold my hand up and

admit that it is not one of my favourite instruments. That said, I can

make the mental jump from an edgy suspicion of the recorder to an appreciation

of the music and its interpretation.

One reviewer of Jill Kemp’s performances has suggested that her ‘playing

is a universe away from any nasty memories you may have of learning this

instrument at school.’ This is certainly true of the interpretation of

all the works on this present CD. The technique is truly impressive. This

also applies to the pianist, Aleksander Szram who makes a major contribution

to the success of this disc. Yet, I have to admit that most of these works

would work just as well for flute rather than recorder. However, I appreciate

that this is a view that all recorder enthusiasts would oppose.

The fine Sonatina Op. 13 by Lennox Berkeley epitomises a work that successfully

balances the piano and the recorder. This neo-baroque or classical work

owes nothing to English pastoralism or neo-romantic traditions. However,

it is full of humour - sometimes black - and allure, if a little unapproachable

on first hearing. The keynote mood is of restless energy with angular

melodies and sharp harmonies. There are some relaxed moments, especially

in the ‘second subject’ of the opening ‘moderato.’ The central ‘adagio’

is dark and introverted. The finale has all the hallmarks of French wit

and brings this work to a sparkling conclusion. I have noted the ‘nods’

to a ‘hornpipe’ before.

I always feel that Arnold’s Sonatina, Op.41 has some rather out of tune

passages. I have not looked at the score, however it never seems ‘quite

right’ to my ear. The work is in typical Arnoldian mood with a number

of delicious moments. The opening ‘cantilena’ has an especially interesting

tune. The middle movement ‘chaconne’ is gloomy; however the final ‘rondo’

restores the sense of fun.

A few months ago I reviewed

Gordon Jacob’s Suite for Recorder and String Quartet in its incarnation

for recorder and string orchestra. There are seven short movements to

this attractive work which was commissioned by Arnold Dolmetsch in 1957.

I felt that a fuller description of the Suite should have been given in

the liner notes. The work begins with a pastoral ‘prelude’ that does indeed

suggest the English landscape. This is followed by a lively ‘English Dance’

that is both exciting and obviously technically difficulty. The ‘Lament’

is not Scottish in mood: to my ear the sultry feel of this piece did not

quite come off. It is the longest movement in this work. After this there

is an exciting ‘Burlesca alla Rumba’ which moves the work away from the

English landscape to ‘points south.’ The ‘Pavane’ is another fine example

of English pastoral: the mood is one of sadness and reflection. However

the hardness of the recorder tends to distract from the introverted feel

to this music. The penultimate movement is a rather eccentric ‘Introduction

and Cadenza’ which continues the temper of the ‘Pavane’ – looking back

to a lost time and place. The final ‘Tarantella’ is another change of

location: this time to sunny Italy. I believe that Jacob called for the

use of the rarely used ‘soprano’ recorder here. It is a fine conclusion

to an excellent work.

I was initially confused by Solitaire. To my mind this Arnold

title is a ballet suite concocted from the two sets of English Dances

with the addition of a short ‘Polka’ and the beautiful ‘Sarabande’. However,

the liner-notes explain that this piece has nothing to do with the ballet:

it was apparently composed for a Players’ tobacco advert and was subsequently

arranged as a whistling tune for John Amis. It was then presented for

flute and piano and after an intervention by John Turner was approved

for recorder and piano. Solitaire is an attractive little miniature

that deserves to be better known.

The Sonata Op.121 by York Bowen is a major contribution to the recorder

repertoire. However, it is this piece more than any other on this disc

that bolsters my contention that many works for recorder would be better

heard played on the flute. I noted in an earlier review that my concern

here was largely stylistic – the counterpoint of the ‘old-world’ sound

of the recorder against the passionate, romantic piano accompaniment.

However, Jill Kemp’s performance modifies this view – she has given a

fine account that evens out (to a large extent) this stylistic disparity.

The present work was commissioned by Arnold Dolmetsch and was composed

during 1946: it was first heard at the Wigmore Hall two years later. The

Sonata has three well-balanced movements: a cool ‘moderato e semplice,’

a meditative ‘andante tranquillo’ and a passionate ‘allegro giocoso’.

The last movement makes use of a descant recorder.

I find Edmund Rubbra’s Meditazioni sopra ‘Coeurs Désolés’ is

a work that has grown on me since first hearing it a year or so ago. It

is founded on a chanson by Josquin de Prés and unfolds as a set of cleverly

constructed variations. It has been considered by Edgar Hunt to be one

of the recorder repertoire’s masterpieces.

The final work is the Fantasy for recorder and string quartet, Op.140

by Malcolm Arnold. It was commissioned for Michala Petri in honour of

the Carnegie Hall’s Centennial Season. It was duly given its premiere

at the Carnegie Hall’s Weill Recital Hall on 15 March 1991. The Fantasy

has five movements, which are a little unbalanced. The technical requirements

are impressive, with a requirement for four different sizes of instrument.

The composer calls for a wide range of playing styles, including flutter-tonguing,

fast double-tonguing, ‘double stopping’ and glissandi. Although there

are some genuine Arnold fingerprints, I find that the overall impact is

disappointing. The second movement is a well written scherzo that sounds

exceedingly complex. The waltz is attractive, but dark. The final ‘rondo’

is the nearest to what we once expected from Arnold’s pen. However, I

felt that the ethos of the Fantasy was effect for effect’s sake. This

is not a work that appeals to me; on the other hand I can understand why

audiences and cognoscenti will be suitably impressed by this music.

I was extremely disappointed by the liner notes and the general presentation

of information on this disc. I do not expect to have to look up dates

of composers or pieces when getting my head around a CD. At home, I am

surrounded by a raft of biographies, works catalogues and musical histories

in my study, but many potential listeners will not be quite as obsessive

about British music as I am. It is not fair to make people search the

‘net to contextualise these pieces. Apart from these deficiencies, there

is a deal of useful information presented in these notes.

This CD will appeal to all recorder enthusiasts: however lovers of English

music will also enjoy these typically engaging works by some of the finest

20th century British composers. Certainly the excellent performances

presented here do all the works an indispensable service.

John France

|