|

|

|

alternatively

CD & Download: Pristine

Classical |

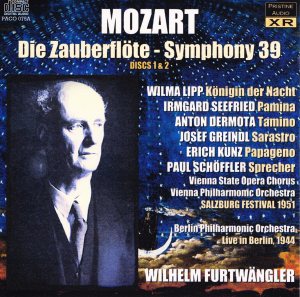

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART

(1756-1791)

Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) - Opera in two acts,

K. 620 (1791) [171:54]

Symphony No. 39 in E flat major, K453 (1788) [27:59]

Wilma Lipp (Queen of the Night)

Wilma Lipp (Queen of the Night)

Irmgard Seefried (Pamina)

Anton Dermota (Tamino)

Josef Greindl (Sarastro)

Erich Kunz (Papageno)

Edith Oravez (Papagena)

Peter Klein (Monostatos) Paul Schöffler (Speaker) Fred Liewehr

(first priest) Franz Hobling (second priest) Christel Goltz (first

lady) Margherita Kenney (second lady) Sieglinde Wagner (third lady)

Hannelore Steffek (first boy) Luise Leitner (second boy) Friedl

Meusburger (third boy) Hans Beirer (first armed man) Franz Bierbach

(second armed man)

Vienna State Opera Chorus,

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (Zauberflöte), Berlin Philharmonic

Orchestra (symphony)/Wilhelm Furtwängler

No libretto included

rec. live, 8 February 1944, State Opera House, Berlin, Germany (Zauberflöte)

6 August 1951, Salzburg Festival, Austria (symphony)

PRISTINE AUDIO XR PACO 075A-B [3 CDs: 75:02 + 45:40 + 79:32]

PRISTINE AUDIO XR PACO 075A-B [3 CDs: 75:02 + 45:40 + 79:32]

|

|

|

All 3 CDs in this set have been transferred by Andrew Rose using

Pristine Audio’s 32-bit XR re-mastering system. There

is a great demand for Furtwängler recordings. Widely accepted

as one of the greatest conductors of the twentieth-century he

has a large legion of admirers. There’s a fascinating

and substantial legacy of recordings, mainly from live performances

and this is cherished by a large and enthusiastic following.

This live performance from the Salzburg Festival of The Magic

Flute took place on 6 August 1951. Although Furtwängler

had a long association with the VPO at the time he had not long

undergone his successful de-Nazification in 1947. It seems that

the performance was broadcast by Austrian Radio but the master

tapes have not survived. Remarkably this recording has been

reconstructed from the secondary source of off-air recordings.

Restorer Andrew Rose states that he is pleased with the results

but less so with the material that he had to work with for the

speech sections.

At this point it seems pertinent to explain a little about the

origins of The Magic Flute. Its composition partially

overlapped with his writing of the Requiem a score he

never lived to complete. A couple of months before his death

Mozart conducted the première of The Magic Flute

in September 1791 at the Theatre auf der Wieden, Vienna. The

opera, Mozart’s first for public consumption rather than

for court use, was an immediate success. It is testimony to

Mozart’s creative capacity that at a time close to the

end of his life, full of torment by failing physical and mental

health, and mounting debts, he could write music of such vital

energy, japery and fantasy. Its success was such that following

its première it was staged over 230 times in its first

ten years at impresario Emanuel Schikaneder’s Theater

auf der Wieden.

The best description I have seen of The Magic Flute is,

“An exotic fairy tale with mystical elements.”

(The Penguin Concise Guide to Opera, ed. Amanda Holden,

Penguin Books, Reprint edition 2005, pg. 281, ISBN: 0-141-01682-5).

With its Masonic subplot, not always highlighted by some directors,

The Magic Flute is one of my very favourite operas. I

have been fortunate to have attended several productions. I

have fond memories of attending a splendid contemporary staging

in September 2009 by director Günter Krämer at the

Deutsche Oper, Berlin. In May 2010 I attended a captivating

production directed by Rosamund Gilmore at the splendid Staatstheater

am Gärtnerplatz in Munich.

For this live 1951 Salzburg Festival production Furtwängler

had at his disposal a fine cast of mainly experienced singers

many associated with the Vienna State Opera. Things get off

to a decent start with the VPO providing an appealing Overture;

if a touch lacking in vitality. The March of the Priests

that commences the second act continues to the same high standard.

Any temptation to take the score too fast is avoided and a sturdy

rhythmic pulse is maintained throughout. For a conductor so

heavily associated with dynamic vivacity, excitement seems strangely

lacking.

Eminent Viennese coloratura soprano Wilma Lipp garnered considerable

admiration as the Queen of the Night a role she played around

400 times. Lipp graced many of Europe’s major opera houses

and was associated with the Vienna State Opera for almost 40

years. Her Queen of the Night is imposing and in her aria O

zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn! (Don’t be afraid,

dear son) there is little evidence of strain. Her bottom

to mid-range is smooth with a creamy timbre. Justly celebrated,

the Queen of the Night’s act two aria Der Hölle

Rache kocht in meinem Herzen (My heart is afire with

hellish vengeance) known as the ‘Vengeance aria’

makes considerable coloratura demands. Here Lipp provides a

controlled rendition with a highly convincing coloratura if

perhaps a touch lacking in excitement. Papageno the loveable

if ridiculous feather-suited, bird-catcher is played by Erich

Kunz, the Vienna-born bass-baritone. In Papageno’s arias

Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja (My profession is

bird catching, you know) and Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen

(I’d like a young wife to comfort me) Kunz is sure

and fluid. I sensed the fragility of the bird-catcher’s

character which is smartly conveyed. Anything but miraculous

are Tamino’s magic flute and Papageno’s magic bells

which sound extremely workaday.

Taking the part of the Pamina is the renowned Bavarian soprano

Irmgard Seefried who was to go on to become a member of the

Vienna State Opera for over 30 years. As Pamina, daughter of

the Queen of the Night, Seefried does not sound especially girlish

yet still proves a fine choice. With good diction Seefried has

a relatively smooth, fluid timbre that comes across effortlessly

in the mid-range. With its lyrical vocal line probably the most

beautiful aria in all opera is Pamina’s Ach, ich fühl's,

es ist verschwunden (Ah, I feel that it has vanished).

In a moving performance the heartbroken Pamina, yearning for

her Tamino, is compassionately portrayed. Seefried is nicely

in tune and seems most comfortable in her mid-range. That said,

I noticed a slight shrill to her top register when forced and

at times she has to snatch to reach. Anton Dermota the Slovenian

tenor knows The Magic Flute well having made his opera

début as the first Man in Armour some fifteen years before

this performance. A stalwart of the Vienna State Opera he was

associated with the company for over four decades. The love-struck

Tamino was one of Dermota’s favourite roles. The Slovenian

gives a compelling, bright and cheerful account of Dies Bildnis

ist bezaubernd schön (This image is captivating

and beautiful). I was moved by his appealing aria Wie

stark ist nicht dein Zauberton (Now I see your powerful

magic spell) when he sings his sweetly tender love song

for Pamina with real conviction and admirable diction.

Experienced Cologne-born tenor Peter Klein as Monostatos was

a regular at the Vienna State Opera and appeared at several

Salzburg festivals. One of my favourite set-pieces is the act

two air Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden (Everyone

feels the joys of love) when Monostatos, a Moor creeps into

the garden and lovingly gazes upon Pamina who is asleep in a

moonlit arbour. A fluid and expressive lyric tenor Klein is

a good actor and is able to add a dark edge to his smooth timbre.

The deep bass Josef Greindl is remembered primarily for his

Wagnerian roles and impressive stage-presence. Here as Sarastro,

Greindl is rock-like, deep and commanding - a true highlight

of the set. Greindl delivers Sarastro’s act two aria with

chorus, O Isis und Osiris (Oh Isis and Osiris),

a prayer to the Gods in the temple, with a chocolate-rich fullness

yet conveying a chilling hint of menace. During the extended

vocal line I was impressed by Greindl’s outstanding breath

control and clear diction. Also from act two Sarastro’s

air In diesen heil'gen Hallen (Within this holy place

revenge is unknown) is sung with such solid confidence.

The three ladies Christel Goltz, Margherita Kenney and Sieglinde

Wagner in their act one quintet ‘Hm, hm, hm, hm’

with Papageno and Tamino give convincing performances. The voices

blend splendidly. A much celebrated set-piece of fantasy opera

is Pamina and Papageno’s first act duet Bei Männern,

welche Liebe fühlen (The gentle love of man and

women) singing of the bliss and selflessness of the unison

of two lovers. The delightfully-toned Seefried as Pamina is

well matched with bass-baritone Kunz a very downtrodden Papageno.

From 5:39 the much loved duet ‘Pa-pa-geno! Pa-pa-pagena!’

between the reunited Papageno and Papagena sung by Kunz and

soprano Edith Oravez comes across agreeably without being exceptional.

But what a glorious melody and such memorable music. Disappointingly

the important flute part sounds rushed and piercing. The act

two trio Soll ich dich, Teurer, nicht mehr sehn? (My

love when we part, will I not see you again?) between Pamina,

Sarastro and Tamino contains much splendid music as well as

a wonderful dash of drama. Sung impressively by Seefried, Greindl

and Dermota this trio is a splendid example of excellent voices

extremely well contrasted.

My two favourite accounts of The Magic Flute are both

played by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (BPO) and were splendidly

recorded at Berlin in 1964 and 1980 respectively. I greatly

admire the compellingly performed double set that Karl Böhm

recorded with the BPO and the RIAS-Kammerchor in Berlin in June

1964. The starry cast is highly characterful and features: Fritz

Wunderlich (Tamino), Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (Papageno), Roberta

Peters (The Queen of the Night), Evelyn Lear (Pamina), Franz

Crass (Sarastro) and Lisa Otto (Papagena). I have the analogue

set digitally re-mastered with original-image bit-processing

technology and full texts with English translations on Deutsche

Grammophon 449 749-2. Another fine version for its elevated

sense of drama is from Herbert von Karajan conducting the BPO

with the Choir of the Deutschen Oper, Berlin and soloists of

the Tölz Boys Choir. Recorded in 1980 at the Berlin Philharmonie

Karajan uses a stellar cast of soloists right down to the minor

roles: Francisco Araiza (Tamino), Gottfried Hornik (Papageno),

Karin Ott (Queen of the Night), Edith Mathis (Pamina), José

van Dam (Sarastro), Gottfried Hornik (Papageno) with Anna Tomowa-Sintow

(first Lady), Agnes Baltsa (second Lady) and Hanna Schwarz (third

Lady). My set is on Deutsche Grammophon 477 9115 - a reissue

with no libretto provided but there is a concise and well written

synopsis.

Included on this Pristine Audio set is a recording of Mozart’s

Symphony No. 39. On the night of 29-30 January 1944 the

home of the BPO the Philharmonie (a former ice skating rink

expanded into a concert hall) on Bernburger Strasse was destroyed

in an Allied bombing raid. Undaunted the BPO used whatever buildings

they could find for their performances including the State Opera

House on Unter den Linden which was still standing - it was

later destroyed by bombing. Recorded on 8 February1944 at the

Berlin State Opera House this is one of a number of Furtwängler’s

wartime performances that were broadcast live on radio by the

state-owned Reich Broadcasting Corporation and recorded on magnetic

tape; many of these reels survived. These were part of a batch

seized by the occupying Soviet Russians and were taken to Moscow.

Some of the performances were released in Soviet Russia on Melodiya.

Thanks to the prevailing spirit of Glasnost the tapes were returned

to Germany in 1987. It is these recordings, returned after over

forty years, that Andrew Rose has used for many of the recordings

released on Pristine Audio.

Furtwängler is best known for his long association with

the BPO whom he first conducted in 1917. He became their principal

in 1922 aged 36 and remained until his death in 1954; a tenure

that was interrupted between the years 1945-47. This Mozart

symphony was given in the midst of the terrors of the Second

World War Berlin. It is worth mentioning the title that music

writer Peter Gutmann uses in the excellent ‘Classical

Notes’ website “Wilhelm Furtwängler:Genius

Forged in the Cauldron of War”. This title for me

encapsulates Furtwängler’s complex and severely challenging

situation so perfectly. Hitler’s Third Reich under Dr.

Joseph Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry used the BPO and

Furtwängler its chief conductor as the crown jewels in

their cultural campaign. Furtwängler’s controversial

wartime role with the players of the BPO and the considerable

advantages they gained from working for the Third Reich still

divides opinion today. Few conductors can have worked in such

a severely pressurised situation as Furtwängler did through

1933/45, the years of National Socialism. All that said I found

Furtwängler’s conducting and the playing of the BPO

from February 1944 at the State Opera House generally lacking

in spirit and vigour. Everything feels heavy with the speeds

coming across as sluggish; especially in the third movement

Menuetto - Trio. The playing of the Finale, Allegro

flows rather better and is definitely more alert but it fails

to redeem what has gone before. Also hindering the overall impression

is the slightly muddy sound and issues with peak distortion.

There is a plethora of recordings of Mozart’s Symphony

No. 39 in the catalogues and many of them are superbly played,

certainly worthy of inclusion in any serious collection. My

reference recording is a powerful and highly compelling account

conducted by Karl Böhm and the BPO; one might describe

it as ‘big band Mozart’. Maestro Böhm recorded

the work in 1966 at the Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin on Deutsche

Grammophon 447 416-2 (c/w Symphonies Nos. 35, 36, 38

Prague, 40, 41 Jupiter). Another admirable account

from the BPO is conducted by Claudio Abbado and was recorded

in 1992 also at the Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin. Abbado is

sparkling yet highly stylish with a beautiful sound that is

lighter in weight; lucid with less vibrato than Böhm. I

have the Abbado recording as part of a 7 CD all-Mozart box set

on Sony Classical 88697761522 (c/w Symphonies Nos. 23,

25, 28, 29, 31, 35, 36, 40, 41, Serenades, Marches,

Divertimenti, Sinfonia concertanti,Masonic

Funeral Music, Marriage of Figaro Overture). Abbado

conducts most of the works and some are conducted by Carlo Maria

Giulini and Zubin Mehta.

The quality of the Furtwängler recordings on this Pristine

Audio release will undoubtedly be a determining factor for many

prospective purchasers. Recorded live at the 1951 Salzburg Festival

the sound quality of The Magic Flute is lacking in definition,

leaving a rather limited orchestral sound. Given the circumstances

of its transfer from off-air recordings the unsatisfying audio

comes as no surprise. I was even more disappointed with Symphony

No. 39 recorded live in 1944 at Berlin’s State Opera

House. Less than gratifying, the congested sound lacks clarity

throughout and peak distortion makes for uncomfortable listening.

Applause has been left in the live performance of the opera

but not the symphony. Curiously, at times, the audience sounds

as if they are clapping underwater. Having said all that I appreciate

that talented audio restoration engineer Andrew Rose can only

work with the material that he has at his disposal. Pristine

Audio seems geared up for downloads and streaming but when customers

such as myself want an actual CD please can the company start

providing professional quality artwork and high quality paper

for the paper insert. The inserts in my set have already started

to tear and the rather shabby effect looks like a homemade effort.

No libretto is included in the set. On the whole the performances

of both The Magic Flute and Symphony No. 39 feel

rather uninspiring with unflattering sound. Apart from historic

significance and their value to the Furtwängler completist

I’m unsure why anyone would choose these recordings over

the many splendid, superbly performed and excellently recorded

alternatives.

Michael Cookson

|

|