|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

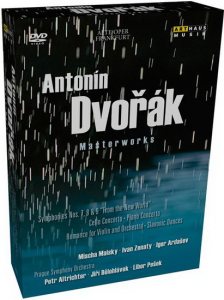

Antonín DVOŘÁK

(1841-1904)

Masterworks

DVD 1

Symphony no.7 in D minor, op.70 (1884-5) [38:24]

Slavonic dances (second series), op.72 (1887) [39:58]

Romance for violin and orchestra, op.11 (1873-7) [14:46]

DVD 2

Symphony no.8 in G major, op.88 (1889) [40:25]

Piano concerto in G minor, op.33 (1876) [42:46]

DVD 3

Symphony no.9 in E minor, op.95 (1893) [42:54]

Cello concerto in B minor, op.104 (1894-5) [40:50]

Ivan Zenaty (violin); Igor Ardašev (piano);Mischa Maisky (cello)

Ivan Zenaty (violin); Igor Ardašev (piano);Mischa Maisky (cello)

Prague Symphony Orchestra/Jiří Bělohlávek

(1); Petr Altrichter (2); Libor Pešek (3)

rec. live, Alte Oper Frankfurt, 1993

Sound: PCM stereo, DD 5.1, DTS 5.1

Picture: NTSC/4:3

Region: 0 (worldwide)

ARTHAUS MUSIK

ARTHAUS MUSIK  107 513 [3 DVDs: 100:00 + 88:00 + 89:00]

107 513 [3 DVDs: 100:00 + 88:00 + 89:00]

|

|

|

How do we justify watching classical music on TV at home, especially

given that most of us experience patently inferior sound reproduction

on our television sets? For some musical events - opera, ballet

- the answer is obvious. The music was specifically written

to be accompanied by visual elements and loses to a hugely significant

degree by their absence.

What about music that was written purely to be listened to in

its own right? Concert halls are, after all, not intrinsic in

themselves to the listening experience: they are merely an economically

efficient means to gather a paying audience together to finance

the performance. I am not denying that watching live music can

be an enjoyable experience or that a caught-on-the-wing, risk-taking

live performance can be utterly thrilling. That excitement is

caused by what one hears, not by what one sees from the

stalls. So why watch a filmed concert at all, rather than listening

to it on CD or the radio from a far better quality audio-only

source? What can we benefit from seeing?

The most likely answer, it seems to me, is that we can profit

most from watching what, before cameras got onto and behind

the stage, only the orchestra could see: how the conductor uses

his technical and artistic skills to coax a performance from

his players. That is, after all, what almost all professionally

filmed concerts, with cameras lingering lovingly on the conductor's

hands and facial expressions, do. It seems hardly necessary

to point out that the - logically justifiable - alternative

of filming from the real concert hall audience’s perspective

would result in DVDs what replicated all those rather sad YouTubevideos

shot on camera phones from the far distance of the back row.

That conclusion suggests, then, that the best reason to watch

concerts on DVD is to study top-flight conductors at work. There

is a great deal of material on offer. Just to take “Golden

Age” examples, Toscanini, Mengelberg, Talich, Stokowski,

Reiner, Munch, Szell, Leinsdorf and Karajan all spring to mind.

The two Teldec DVDs The Art of Conducting are sources

of both rare historic material and constant artistic illumination.

While that may be the best reason to watch concerts on

DVD, it is not the only one. So while these three conveniently-boxed

discs of Dvořák's music, as performed in a series

of concerts in the Alte Oper Frankfurt in 1993, may not provide

as much food for musical thought as one featuring one of the

conductors listed above, they do undeniably offer experiences

that are simply very enjoyable.

All three of the conductors represented here are Czech and completely

at home in Dvořák’s idiom. Moreover, two of

them had, when these recordings were made, already enjoyed a

close association with the Prague Symphony Orchestra: Jiri Bělohlávek

had been its principal conductor from 1977 until 1990, after

which Petr Altrichter had taken up the reins for a couple of

years.

The first disc is directed by Bělohlávek - even

though it’s said to be Altrichter on the rear of the box

- and gives us a well-played if rather strait-laced account

of the seventh symphony. That is followed by the second set

of Slavonic Dances in a far more relaxed and unbuttoned performance,

though one that only manages to hint at the musical depths unearthed

by Vaclav Talich in a superb televised performance with the

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra from 1955 (available on Supraphon

DVD SU7010-9). Czech violinist Ivan Zenaty brings the disc to

a close with a winning account of the admittedly rather slight

Romance for violin and orchestra op.11.

The disc 2 performances headed up by Altrichter are of the eighth

symphony and the piano concerto.

Reversing the Arthaus Musik marketing department’s billing,

the concerto is positioned first on the disc, just as one imagines

it was in the concert. Czech pianist Igor Ardašev, still

in his 20s when this concert was filmed, displays a rather detached

and undemonstrative stage presence. That is immediately belied

by his warm, flowing performance of the concerto’s solo

part. This account is, in fact, anything but detached: Ardašev

is clearly fully engaged with the work and is ably supported

by a strong and idiomatic contribution from the orchestra. Even

though the concerto lacks the obvious Dvorak “big tune”

that gives, say, the New World symphony or the cello

concerto their popular appeal, a performance like this one demonstrates

what a great shame it is that it remains so rarely heard. Petr

Altrichter’s distinctive account of the symphony is hardly

less successful. Lively, well-sprung rhythms emphasise the innate

Slavonic liveliness that is the score’s most obvious characteristic.

The conductor also ensures that its occasional darker and more

dramatic hues, harking back to the seventh symphony, also emerge

powerfully and to great effect.

Although the New World is billed first on the packaging,

the set's third disc actually opens with the Cello Concerto.

Superbly technically assured, soloist Mischa Maisky crouches

over his instrument so closely that they sometimes almost seem

joined into a single entity. His intensely dramatic account,

full of insight and authority from his very first entry, very

understandably goes down a storm with the capacity Frankfurt

audience. I imagine that Libor Pešek has conducted the

New World - something of a natural calling-card for Czech

conductors - on very many occasions, but the performance here

is fresh and invigorating from the opening bar and takes nothing

for granted. To their great credit, the Prague musicians - who

impressed me very much on all three discs in this set - respond

with equal enthusiasm, making for an altogether enjoyable 42

minutes or so that seems to pass much more quickly.

From a technical point of view, things are very well done indeed

by what seems to be an expert technical crew - presumably largely

British, if the names on the final credits are a guide. The

sound reproduction is well integrated yet clear enough to hear

fine individual detail. Camera shots are judiciously chosen

with close regard for the scores' requirements. The stage lighting

is also well judged, retaining a concert hall atmosphere while

ensuring that we are offered the best visual experience. Indeed,

viewers of a more delicate sensibility may find the images rather

too detailed once or twice, as we clearly see drops of sweat

falling repeatedly from the visibly overheated Petr Altrichter’s

brow.

I had just one small post-production quibble, though I concede

that it may be peculiar to my own TV/DVD set-up. The booklet

notes list an opening track of a minute or so on each disc before

the first track of music: I presume that was for an opening

title sequence and the arrival of the conductor and soloist

on stage. For some reason, my DVD player automatically skipped

that, as well as any menu, and just began the first track of

music with no further ado which was a little annoying. It may

well be that your own player will behave rather better: in any

case, the glitch was certainly not enough to spoil the overall

enjoyment that Dvorak’s scores - and these discs - offer

in such generous abundance.

Rob Maynard

see also review of DVD 1 (Symphony 7) by John

Sheppard and DVD 2 (Symphony 8) by Colin

Clarke

Masterwork Index: Cello

concerto ~~ Symphony

7 ~~ Symphony

8 ~~ Symphony

9

|

|