|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

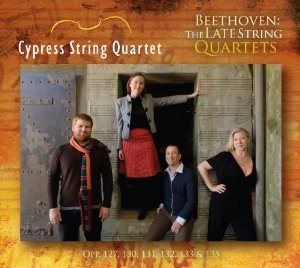

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

The late string quartets

String quartet in E flat major, Op. 127 (1825) [36:30]

String quartet in A minor, Op. 132 (1825) [43:18]

String quartet in B flat major, Op. 130 (with Grosse Fuge,

Op. 133) (1825) [49:38]

Alternative finale to Op. 130 [10:48]

String quartet in C sharp minor, Op. 131 (1826) [38:35]

String quartet in F major, Op. 135 (1826) [24:12]

Cypress String Quartet (Cecily Ward (violin); Tom Stone (violin);

Ethan Filner (viola); Jennifer Kloetzel (cello))

Cypress String Quartet (Cecily Ward (violin); Tom Stone (violin);

Ethan Filner (viola); Jennifer Kloetzel (cello))

rec. 2012, Skywalker Sound Scoring Stage, California. DDD

CYPRESS STRING QUARTET CSQBC012 [3 CDs: 79:48 + 61:26 + 62:47]

CYPRESS STRING QUARTET CSQBC012 [3 CDs: 79:48 + 61:26 + 62:47]

|

|

|

I first heard the late string quartets of Beethoven in my teens,

on a budget price LP on the French Musidisc label. I don’t

remember much about the performances; one movement that sticks

in my mind is the slow movement of Op. 127, which was played

at an expansive tempo, and took around twenty minutes. However

I do remember the liner-notes, which were obviously translated

by someone for whom English was not their first language. One

sentence I will always treasure said (something along the lines

of) “It is not possible to love Beethoven truly who has

not heard him beat his heart out in these late Quatuors”.

Putting aside the mangled expression, I think the writer is

perfectly correct. To me the late quartets are the crowning

glory of Beethoven’s output. Emotionally they encompass

the most seraphic, the most ecstatic, and some of the most radical

music Beethoven wrote. It is a paradox that in this, his most

inward-looking period, the composer achieved a universal, even

fundamental musical language.

The Cypress String Quartet obviously has the technical armoury

required to tackle these demanding works. The group started

playing the Beethoven quartets soon after its formation in 1996,

and this recording bears the hallmark of long and intensive

study. The slow introduction to the opening movement of Op.

127 and the following Allegro are taken as marked. The

subito piano and pause markings that are so frequent

in these scores are rendered most scrupulously. The group’s

phrasing is also done with great care. Most quartets join phrases

together, so that the end of one dovetails into the beginning

of the next, but the Cypresses do not smooth over this gap.

The wonderful Adagio non troppo e molto cantabile is

not quite as luxurious as it could be; the Cypresses take this

at 14:44 versus the Alban Berg Quartet’s 16:36. The leader’s

intonation fell away a little towards the end of the movement.

Mention must, however, be made of the cellist Jennifer Kloetzel,

whose line is unfailingly rich and beautiful. The sforzandi

in the finale are again played with great exactness, and the

attention to dynamic detail generally is outstanding.

The first movement of Op. 132 elicits a more driven performance.

The Cypress’s sparing use of vibrato is noticeable here.

The second movement brings about a relaxation of the tension,

with superb contributions from the viola. The long chorale-like

phrases of the Molto adagio allow the group’s intelligent

use of vibrato to come into its own. The careful dynamic shaping

in the finale allows the ear to rest from the forte and

fortissimo writing. This is a majestic reading of great

concentration.

Op. 130 is presented with the Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 as

the finale; the alternative finale is also included on the disc.

I noticed in this quartet how often Beethoven pits the two violins

against the viola and cello, and these exchanges in particular

are played quite delightfully. Along with the finale to the

Hammerklavier Sonata Op. 106, the Grosse Fuge

is one of Beethoven’s most extended contrapuntal movements.

From the unison opening this performance has quite a symphonic

impact. The Cypresses do not attempt to smooth over the uncompromising

nature of the writing; their performance seems to draw energy

from Beethoven’s attempt to split the musical atom.

Op. 131 was a quartet that I didn’t know as well as the

others. The structure is quite experimental, being divided into

seven movements, all quite short except for the slow movement,

which is another Andante non troppo e molto cantabile.

Initially I was less convinced of the group’s reading

of this than with the other quartets, but a second hearing removed

these doubts. They play the fugal opening movement with concentration

and beauty of tone. After these musical experiments Beethoven

returned to a more familiar utterance in Op. 135, the first

movement of which recalls the classicism of the Op. 18 quartets.

The episode in the Scherzo, in which an obstinate figure swells

into something frighteningly intense, is superbly done. Moments

like these remind us how radical these works must have sounded

to Beethoven’s contemporaries, and how modern they still

are.

A big part of the group’s sound derives from the wonderful

instruments they have at their disposal; these comprise Stradivarius

and Bergonzi violins, a Bellarosa viola and an Hieronymus Amati

II cello. Other aspects of the group’s playing derive

from the historically informed performance movement. Their very

selective use of vibrato is notable. Another one is the democratic

nature of the ensemble. Earlier quartets such as the Amadeus

were much more leader-dominated; there was no doubt as to who

was in the driver’s seat. This has given way in recent

times to a desire to take a more inclusive approach; contemporary

ensembles like the Emerson Quartet go so far as to alternate

the leadership between the violins. To me the Cypresses take

this tendency a little too far, in that the leader can be a

little recessive at times. The cello and viola are such superb

players, they can - at least tonally - tend to dominate the

ensemble. There is obviously no problem with Cecily Ward’s

instrument, so I can only think that her rather low-key leadership

is a conscious choice. When she does cut loose occasionally,

as in the Presto of Op. 131, one can hear what a good

player she is, and one wishes she would do so more often.

The Alban Berg Quartet takes a more traditional approach to

these quartets, and is a little smoother in its phrasing. However

the discords and syncopated rhythms that pervade these scores

are not glossed over. The Alban Berg has the security of a group

of long standing, and that is rooted in a European string quartet

tradition. There is certainly no mistaking the authority of

Günther Pichler’s leadership, and the music always

has direction. Timings are quite similar to those of the Cypress

Quartet - with the exception of the slow movement of Op. 127

as referred to above. In Op. 131, I felt that their reading

had a better grasp of the pattern underlying its heterogeneous

structure. The Alban Berg Quartet Beethoven cycle was made over

a period of five years, and includes some ADD as well as DDD

recordings. As such the sound-picture has less immediacy than

the Cypress Quartet’s self-produced recording, which has

an attractive warmth without being too lush. The photographs

in the liner-notes have the Cypress Quartet players sitting

(from left to right) violins, cello, viola. If the order had

been violins, viola, cello, this would have made the sound-stage

a little more distinct.

Despite the minor quibbles I have expressed, the Cypress Quartet’s

Beethoven readings have numerous virtues. The interpretations

are well thought through, and the group’s beauty of tone

and unanimity of ensemble are unfailing. I look forward to more

of this virtuoso American quartet’s Beethoven - particularly

the Rasumovskys, with their prominent cello line.

Guy Aron

|

|