|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

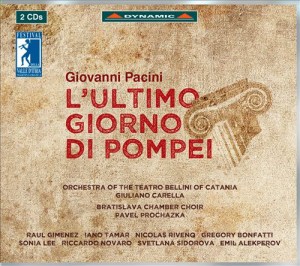

Giovanni PACINI (1796-1867)

L’ultimo giorno di Pompei (1825) [152.21]

Raul Gimenez (tenor) - Appio Diomede, Iano Tamar (soprano) - Ottavia,

Nicolas Revenq (baritone) - Sallustio, Gregory Bonfatti (tenor)

- Pubblio, Sonia Lee (soprano) - Menenio, Riccardo Novaro (bass)

- High Priest, Svetlana Sidorova (soprano) - Clodio, Emil Alekperov

(tenor) - Fausto

Raul Gimenez (tenor) - Appio Diomede, Iano Tamar (soprano) - Ottavia,

Nicolas Revenq (baritone) - Sallustio, Gregory Bonfatti (tenor)

- Pubblio, Sonia Lee (soprano) - Menenio, Riccardo Novaro (bass)

- High Priest, Svetlana Sidorova (soprano) - Clodio, Emil Alekperov

(tenor) - Fausto

Bratislava Chamber Choir, Orchestra of the Teatro Bellini Catania/Giuliano

Capella

rec. Martina Franca Palazzo Ducale, 2-4 August 1996 (formerly issued

in 1999)

DYNAMIC CDS 729/1-2 [76.46 + 75.35]

DYNAMIC CDS 729/1-2 [76.46 + 75.35]

|

|

|

Giovanni Pacini was one of those Italian composers who had

a degree of success in the early nineteenth century but who

were eventually eclipsed by the greater talents of Rossini,

Bellini, Donizetti and ultimately Verdi, and who thereafter

disappeared from the repertory for a century or more. In fact

Pacini disappeared during his own lifetime. After 1833 he, like

Rossini, retired from the operatic stage; unlike Rossini, he

then staged a ‘comeback’ in the 1840s with scores

such as Saffo and Maria Regina d’Inghilterra,

both of which have recently been revived and recorded and on

which Pacini’s reputation (such as it is) nowadays largely

rests. But by the 1840s his style had begun to seem old-fashioned,

and his eclipse by the up-and-coming Verdi was this time total.

He was apparently no musical technician - Rossini had said in

one of his more waspish bon mots “God help us if

he knew music, for then no one could resist him” - and

his style indeed closely resembles that of the later Rossini

opera grande such as William Tell and Moses.

Actually L’ultimo giorno di Pompei was written

before either of the Paris versions of these Rossini works,

but his model was clearly Rossini’s earlier works in the

same serious vein such as Ermione and Semiramide.

There is the same delight in coloratura display for its

own sake, but there is also a movement towards concerted numbers

in which the various singers are set off one against another;

and some of these passages have an impetus which can also be

seen to anticipate early Verdi. Indeed, there is only one extended

solo passage, the tenor aria (with chorus) Oh mi crudele

affetto! (CD 2, tracks 11-13)where the sheer

difficulty of the writing has almost certainly militated against

any prospect of star Italian tenors performing it in recital.

The last days of Pompeii might be suspected of being

based on Bulwer Lytton, whose historical novels also inspired

Wagner’s Rienzi. No such luck. What we have here

is a pretty well bog-standard story of love and betrayal with

the historical setting almost an irrelevance until the volcano

blows its top (quite spectacularly, in a passage which seems

to have left its mark on Berlioz’s Troyens) at

the very end. The leading tenor is the villain of the piece

- Rossini had already set a precedent for this by casting Iago

as a tenor in his setting of Otello - and when he is

rejected by the wife of the local magistrate, he - with the

aid of his accomplice, also a tenor - accuses her of adultery.

She is condemned by her husband to be buried alive. There are

echoes here of Spontini’s Vestale as well as an

anticipation of Verdi’s Aida. When the conspirators

rather unconvincingly have a fit of remorse brought on by the

eruption of Vesuvius and confess their perjury, they are condemned

to be buried alive in her place. She and her husband flee the

city as “an enormous quantity of ashes and pumice”

descends, leaving the rest of the citizens to fend for themselves.

This rather dubiously ‘happy ending’ brings the

opera to an abrupt close.

The main problem lies with the music itself, which is always

expertly constructed and at times reminds the listener of Rossini,

or Donizetti, or Bellini, or Spontini, or Berlioz, or early

Verdi. But the imitations, good as they are, never quite achieve

a profile of their own and one is left with an impression of

a generic bel canto opera - although the same could be

said of quite a few operas by Rossini, or Donizetti. There are

some novel touches, including use of the harp to lend period

colour, and the two villainous tenors have a brilliant duet

(CD1, track 25) where the coloratura embellishments do

not quite succeed in destroying the dramatic impact of their

plot. There is a seemingly insatiable public appetite for obscure

bel canto operas, so those who missed this recording

on its initial issue will be delighted to snap it up now.

We are not likely ever to get a second recording of this opera,

so it is excellent news that this one is so good. Pacini was

born in Catania, and his home town does him proud. It is perhaps

somewhat surprising that they had to import a chorus from Bratislava,

but they sing very well and are almost certainly an improvement

on what any local Italian opera chorus would have delivered.

Gimenez and Tamar both cope superbly with the fiendishly difficult

coloratura passages they have to negotiate; Bonfatti

is a good foil for Gimenez in their duet passages, and Rivenq

as the magistrate is suitably noble. Carella conducts with enthusiasm

and a real feeling for the idiom; it is hardly his fault that

the many conventional processional passages are so extended.

The whole performance is indeed excellent, a considerable cut

above many of the revivals of this repertory in Italian provincial

opera houses which we more usually get served up on disc. It

gives a good impression of Pacini’s style, with all its

faults and all its felicities well portrayed and in focus.

The recording comes from a live performance, but there are not

too many stage noises apart from the tramping noises during

the procession scenes - although some of them, like the onstage

squeaking of the scenery, are somewhat mysterious. The audience

is generally very well-behaved. The booklet gives a full track-listing

and some details about Pacini himself, but the curtailed plot

synopsis is not very helpful. The libretto (in both Italian

and English) is available online and is helpfully crammed onto

a mere thirteen pages (although the typeface could be larger)

together with CD cues. The translation itself is not a literary

masterpiece - the final chorus beginning “Si fugga …

e dove?” is rendered rather inelegantly as “Let

us abscond … but where?” which makes the citizens

of Pompeii sound as if they are doing a moonlight flit - but

it conveys the sense of the action adequately.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

|

|