|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS |

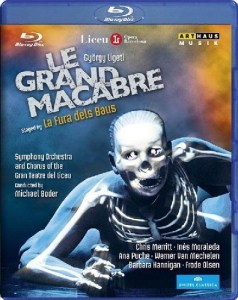

György LIGETI

(1923-2006)

Le Grand Macabre (1974-77, rev. 1996) [122:00]

Opera in two acts (four scenes). Libretto by György Ligeti

in collaboration with Michael Meschke, based on a work by Michel

de Ghelderode. Revised version, sung in English with subtitles in

various languages.

Piet the Pot: Chris Merritt; Amando: Inés Moraleda; Amanda:

Ana Puche;

Piet the Pot: Chris Merritt; Amando: Inés Moraleda; Amanda:

Ana Puche;

Nekrotzar: Werner Van Mechelen; Astradamors: Frode Olsen; Mescalina:

Ning Liang;

Venus/Gepopo: Barbara Hannigan; Prince Go-Go: Brian Asawa; White

Minister:

Francisco Vas; Black Minister: Simon Butteriss; Ruffiak: Gabriel

Diap; Schablack: Miquel Rosales; Schabernack: Ramon Grau

Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu/Michael

Boder

Stage Direction: Àlex Ollé (La Fura dels Baus) in

collaboration with Valentina Carrasco

Set Designer: Alfons Flores; Video: Franc Aleu; Costume Designer:

Lluc Castells;

Lighting Designer: Peter van Praet; Chorus Master: José Luís

Basso; Video Director: Xavi Bové

A co-production of Gran Teatre del Liceu, Théâtre Royal

de la Monnaie, Opera di Roma, and English National Opera

rec. live from Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona, Spain, November

2011

ARTHAUS MUSIK 108 058

ARTHAUS MUSIK 108 058  [122:00 + 42:00 (bonus material)]

[122:00 + 42:00 (bonus material)]

|

|

|

Ligeti’s sole opera, La Grand Macabre, was by all

accounts his most ambitious work and one that gave him the most

heartburn, at least concerning the staging of it. He composed

the opera between 1974 and 1977 and the first performance took

place in Stockholm in Swedish on 12 April 1978. The opera was

based on a 1934 play in French by the little known Belgian,

Michel de Ghelderode, and the libretto was written by the composer

in collaboration with Michael Meschke in German and Swedish.

The first production was counted a success, which of course

pleased Ligeti greatly. La Grand Macabre would receive

more than twenty different stagings during the next two decades,

though Ligeti was not satisfied to varying degrees with any

of them. He found they misrepresented his conception of the

play and his adaptation of it. He also decided that the opera

needed revising and he pruned much spoken dialogue and strengthened

the musical element. He also now felt that the work should be

performed in the vernacular. He revised the opera in 1996 and

that is the version performed now. There is a recording of the

original version in German on Wergo conducted by Elgar Howarth

whom Ligeti requested to conduct it. Then in 1997 Peter Sellars

staged the revised version with a cast conducted by Esa-Pekka

Salonen. According to Richard Steinetz in his highly regarded

study of the composer, György Ligeti: Music of the Imagination,

Sellars completely distorted the work by staging it in a “post-nuclear”

setting, with a stage design like some lunar landscape. Ligeti

disowned the production, though he highly approved of the musical

performance that was conducted by Salonen. It is this production

from a performance in Paris in 1998 that is preserved on CD

as part of Sony’s Ligeti Edition. It can be considered

a definitive performance, if only as an audio version. The opera,

however, cries out for video and that’s where this new

production comes in. It is the first representation on DVD and

Blu-ray of the opera.

The opera takes place in a fictional Brueghelland, based on

the Gothic paintings of Pieter Brueghel the Elder and also Hieronymous

Bosch, during anytime-no particular period is indicated. Into

this land, the figure of Death, the Grim Reaper, referred to

as the Grand Macabre, one Nekrotzar, comes to announce the end

of the world at midnight. The staging for the production here

distorts what Ligeti envisioned by substituting a large fiberglass

female torso for the graveyard of the original libretto. The

torso, which is based on a real person, the singer Claudia Schneider,

serves the function of providing entrances and exits for all

of the characters through the openings of her orifices including

the nipples of her breasts. She in fact is at the center of

the action. With special lighting effects, she changes color

and shape-at one point turning into a skeleton and at another

merging into the starry sky of the universe. She even is set

on fire at the end of the second scene. While very impressive

by herself, this human torso can also detract from the actors

and the action taking place on and around her.

The opera is divided into two acts and each has two scenes,

though these run together with only orchestral interludes separating

them. After a prelude performed by car horns, the opera opens

with a sort of narrator, the drunken Piet the Pot, who is more

of an observer than anything else, though he Nekrotzar soon

turns him into his slave. Piet the Pot observes a pair of lovers

who engage in sexual encounters and who are both portrayed by

female singers, though one is supposed to be a man, Amando (Spermando

in Ligeti’s original version) and the other a woman, Amanda

(Clitoria in the first version). As staged here they have a

sort of unisex appeal as both are “costumed” in

reddish costumes that represent the human muscular system. They

have the most traditional music in the opera in that it is actually

lyrical and beautifully sung. Most of the other characters declaim

their parts with a combination of singing and speaking, parlando

rather than Sprechstimme, in the German sense. Nekrotzar

makes his entrance in the opera by descending from the torso’s

mouth. His appearance is quite unworldly, as he is dressed in

a white suit and is completely bald but with his nerves showing

at the back of his head. There is something very cold and unreal

about him. His costume is supposed to represent the nervous

system.

The second scene of the first act is devoted to the sadomasochistic

behavior of the astronomer Astradamors and his terrifying wife

Mescalina. He is cross-dressed, in women’s underwear,

while she has on a costume that reveals her sagging breasts

that only adds to her decadence. After tiring of him, Mescalina

falls asleep and dreams that the goddess Venus will send her

a “well hung” man. In this scene Piet the Pot returns

and recognizes his old friend Astradamors. Venus appears at

the top of the torso, as a very feminine figure with long, blond

hair and wearing a pink tulle costume with long hair-like fringes.

She answers Mescalina by providing her Nekrotzar to fill the

bill of her masculine ideal. At this point the whole ensemble

are singing their different parts simultaneously in a rather

ingenious chorus. As the scene ends, Piet, Astradamors, and

Nekrotzar see a comet that portends the end of the world and

the torso is set aflame.

The second act begins with another prelude, this time on doorbells.

The first scene shifts to the palace of the Prince Go-Go and

is introduced by the prince’s ministers, one white and

the other black. For this production the black minister is wearing

a blue suit and the white one, a red suit-representing the veins

and arteries of the circulatory system. The ministers have a

catalogue duet of name-calling where they go through the alphabet

and come up with words or phrases for each letter. It is interesting

that in this production they use much stronger profanity (as

is also the case elsewhere) than in the 1998 Paris production

from which the Salonen recording was taken. Indeed, there are

changes in the characters’ lines throughout the libretto

in the new version, though both are based on the opera’s

revision. There is much humor, some of it scatological, in this

duet. One of the funniest though, is for the letter “t”

where they come up with “toilet brush” and each

holds up said item. The ministers treat their prince with due

derision. He is a rather rotund figure, reminding me more than

a little of humpty-dumpty, and is cast with a soprano voice,

sung here as in other productions by a counter-tenor. Use of

the counter-tenor could easily be viewed as a parody of Handel’s

operatic heroes. When he asks for his horse, he is supposed

to get only a rocking-horse (according to the libretto). In

this production, however, the “rocking-horse” turns

out to be a large rubber ball with two nipple-like protuberances.

The ministers make Prince Go-Go wear a crown that looks like

a cage and that hurts the prince’s head. Into this scene

via the large torso part of which now appears as “her”

intestines arrives the chief of the secret police, Gepopo. This

role is played by a female dressed in a green military suit

with helmet and she soon takes charge. Gepopo’s part is

scored for a high soprano and is the same singer as in the part

of Venus. As Gepopo, the singer has coloratura or rather hyper-exaggeration

of coloratura solos that go on and on. It is a real virtuoso

role and takes a superb actor as well as singer. Barbara Hannigan

who does the part here extremely well has made a specialty of

this type of singing in Ligeti, as she has performed in the

Aventures,Nouvelles Aventures, and Mysteries

of the Macabre on numerous occasions. (I was fortunate to

hear her in these works in New York several years ago at an

all-Ligeti concert.) Other police join Gepopo on stage while

the offstage chorus sings “our great leader” over

and over, “extolling” the prince. Netkrotzar, Piet

the Pot, and Astradamors reappear Nekrotzar proclaims the end

of the world, but Piet and Astradamors get him drunk on wine

(Nekrotzar thinks it is blood!).

In the last scene Piet and Astradamors awaken and imagine they

have gone to heaven, while Nekrotzar also wakes up from his

drunken state and is disappointed that the world has not ended.

He starts to shrivel up until he completely disappears. The

other characters begin to appear on stage and by the end of

the opera they have all returned and sing the moral of the story

that no one knows when his or her hour will come. One might

as well enjoy life and be merry! Before the end of the opera

Ligeti inserts a beautiful mirror canon played by the strings

that depicts the sunrise and Nekrotzar’s demise. Ligeti

ends the opera with an ingenious passacaglia sung by Amando

and Amanda and joined finally by the other singers.

For his opera, Ligeti has borrowed from older music forms and

operatic conventions and quoted or referred to such diverse

themes as Offenbach’s Can-can and the bass line opening

of the finale of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony. As Steinitz

points out in his book, it is surprising how little the composer

uses his best-known stylistic devices from the 1960s and 70s,

such as micro-polyphony. Rather he looks backward to some of

his earlier works, for example, Musica ricercata, and

the opera also looks forward to his later music. In this sense,

the Le Grand Macabre is a transitional work. It was his

only completed attempt at opera, but he planned to compose another

one on his favorite Alice in Wonderland. Unfortunately,

he did not live long enough to accomplish this dream. What he

produced, however, is one of the greatest theatrical works of

the late 20th Century: an opera that contains several

layers of meaning. It is farce, theater of the absurd, but also

biting political satire. Ligeti of course had suffered greatly

under both Nazism and Communism and so found political satire

a logical theme for his opera. At the same time, the opera is

a morality tale much as Stravinsky’s The Rake’s

Progress is, with the moral clearly stated at the end of

the work.

This production has divided critics and they have either praised

it or panned it. One wonders what Ligeti himself would have

made of it. As mentioned earlier, he was not satisfied to varying

degrees with any of the productions of his work. I found it

to be very convincing and entertaining, for the most part, and

appropriate to the opera’s story-unlike the travesty that

Martin Kušej and the Bavarian State Opera perpetrated on

Dvořák’s Rusalka. I cannot imagine

this particular staging of Le Grand Macabre being done

any better than the production mounted here. As for the singing

and orchestral playing, both are also top-notch. The singers,

without exception, are superb in their roles, with special mention

to Barbara Hannigan as Gepopo and Brian Asawa as Prince Go-Go.

The orchestra features its percussion section with all kinds

of unusual “instruments,” including pots and pans

and crockery in addition to the car horns and doorbells that

depict the sounds of the outside world. All of these sound effects

are produced mechanically rather than electronically. The brass

and strings also require real virtuosity, and the Barcelona

orchestra does not disappoint-though there are places where

Salonen’s Philharmonia sounds a bit more secure in the

Sony audio recording. My only disappointment is that the viewer

does not get to see the orchestra performing its preludes with

the car horns and doorbells. Instead the scenes begin with a

video of the real Claudia Schneider who thinks she is dying.

The videos then merge seamlessly into the enormous “Claudia”

torso for the stage setting. At the end of the opera, the production

again reverts to the video with Claudia flushing the toilet.

I could have done without that.

A real bonus is the lengthy documentary, “Fear to Death,”

on the making of the opera by the stage directors, Àlex

Ollé and Valentina Carrasco; set designer, Alfons Flores;

and costume designer, Lluc Castells. They go into great detail

on the creation of the Claudio torso and on the various costumes

and their relationship to the systems of the human body. There

are subtitles for the documentary as well, since the discussion

is conducted in Spanish. In addition to this documentary, there

is a much shorter interview in German with the conductor, Michael

Boder, who explains the musical aspects of the opera. As in

the case of other Blu-rays, trailers of other opera productions

are included as well. I have not seen the DVD version of this

production, but I can say that the Blu-ray, both in sound and

picture leaves nothing to be desired. Both are crisp and clear.

For me this is one of the most important discs yet issued this

year. It is certainly one of the best that I have had the pleasure

to review. As it is the only option for this opera on DVD or

Blu-ray, it is self-recommending. Viewers should be warned,

however, that the nearly pornographic production may be disturbing

and some may find it downright appalling. For those, I would

recommend sticking with Salonen’s audio recording until

a different production comes along. The two versions are different

enough that I am happy to have both in my collection.

Leslie Wright

|

|