|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

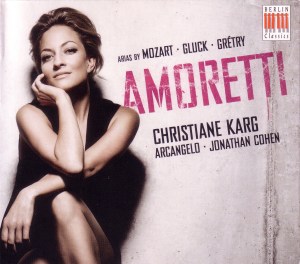

Amoretti

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756

- 1791)

La finta semplice, KV 51

1. Amoretti [4:58]

Ascanio in Alba, KV 111

2. Ferma aspetta ... [3:56]

3. Infelici affetti miei [5:25]

André GRETRY (1741

- 1813)

La fausse magie

4. Comme un éclair [6:04]

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART

Mitridate, re di Ponto, KV 87

5. Lungi da te [10:14]

Christoph Willibald GLUCK (1714

- 1787)

Orphée et Eurydice

6. Soumis au silence [2:04]

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART

Il sogno di Scipione, KV 126

7. Biancheggia [7:14]

André GRETRY

Silvain

8. Il va venir ... Pardonne, o mon juge [5:22]

Lucile

9. Au bien supreme [2:36]

Christoph Willibald GLUCK

Il parnaso confuso

10. Sacre piante [10:12]

Telemaco ossia l’isola di Circe

11. In mezo a un mar crudele [5:32]

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART

Lucio SillaKV 135

12. Odo, o mi sembra udir... [1:13]

13. Fra i pensier [3:22]

Christoph Willibald GLUCK

Iphigénie en Aulide

14. Adieu [4:30]

Christiane Karg (soprano), Arcangelo/Jonathan Cohen

Christiane Karg (soprano), Arcangelo/Jonathan Cohen

rec. 7-10 February 2012 at St Jude’s, Hampstead Garden Suburb

Sung texts with German and English translations enclosed

BERLIN CLASSICS 0300389BC [72:52]

BERLIN CLASSICS 0300389BC [72:52]

|

|

|

This lovely disc encompasses arias from twelve operas composed

within a ten-year-period by three composers from roughly three

different generations. His first reform opera, Orfeo ed Euridice

was premiered as early as 1762 - three years before Il parnaso

confuso and Telemaco, which are the earliest works

here. The French version, appearing in 1774, was however a quite

substantial reworking of the Italian ‘original’

and can thus be regarded as a different work. All five Mozart

operas represented here belong to his juvenile years, La

finta semplice even written before he turned teenager. It

is also this opera that lends the title of the album, Amoretti,

the plural of ‘Amoretto’, the Italian for ‘Cupid’.

Practically none of the arias here can be regarded as standards,

not even L’Amour’s little arietta from Orphée

or Iphigénie’s Adieu from Iphigénie

en Aulide. Three of the arias are even premiere recordings.

The young Bavarian soprano Christiane Karg has, since her debut

at the Salzburg Festival in 2006 had a rapid rise to stardom

and in October 2010 she was awarded the Echo Klassik prize as

Newcomer of the Year by the German Phono Academy for her first

Lieder CD. I haven’t heard that disc but from what I hear

on the present disc I can understand the accolade. She has a

truly beautiful lyric soprano with angelic high notes, she nuances

exquisitely and her pianissimo singing is ravishing. All this

is apparent in the very first aria, the one from La finta

semplice. In the recitative and aria from Ascanio in

Alba (trs. 2-3) she also turns out to possess dramatic expressiveness

as well. The aria proper is a good example of the young Mozart’s

creative power. I can’t resist quoting Charles Osborne

in his The Complete Operas of Mozart on this aria:

‘With Silvia’s recitative and aria, ‘Infelice

affetti miei’ (No. 23), we are suddenly transported ahead

to the world of mature Mozart. The accompanied recitative preceding

the aria, in which Silvia wrestles with the two images of love,

chaste and erotic, which have revealed themselves to her, is

written with the insight not of an adolescent but of the musical

psychologist who was to bring similar but no greater gifts to

the plight of Fiordiligi in Così fan tutte. The

comment of the string accompaniment is as understanding, as

consoling, as though we were listening to that opera, and not

to a sérénade d’occasion at a royal

court. The aria which follows is a sad and affecting adagio

in which Silvia asks the gods to restore her lost innocence:

a touching but also astonishing piece to come from the pen of

the fifteen-year-old Mozart.’

In his day André Grétry was one of the leading

composers of opera. He wrote about fifty works in the genre

and Zémire et Azor (1771) and Richard Coeur-de-lion

(1784) are regarded as his masterpieces. It seems that his music

is out of fashion today but there do exist quite a lot of recordings,

including a live recording (Somm)

under Sir Thomas Beecham (he championed Grétry’s

music) of Zémire et Azor from 1955 and a studio

recording of Richard Coeur-de-lion on EMI with a starry

French cast including Jules Bastin, Mady Mesplé and Charles

Burles. Checking on Operabase I found some productions during

2011 and 2012 and one coming up in June 2013 at Liège,

conducted by Claudio Scimone. The opera is Guillaume Tell,

first performed in 1791 and thus preceding Rossini’s opera

by 28 years. 2013 is the bicentenary of Grétry’s

death but this celebration will undoubtedly be somewhat overshadowed

by the celebrations for Verdi and Wagner next year.

“I was at once attracted by this delicate and delightful

music..”, wrote Beecham in his autobiography on discovering

Grétry’s music and it is very easy to like. The

aria from La fausse magie (tr. 6) is agreeably melodious

but also requires some virtuoso singing, and Christiane Karg

on top of everything else tosses off excellent coloratura. She

is a lovely L’Amour in the aria from Orphée

and dramatic and intense in the whirling aria from Il sogno

di Scipione, the coloratura again assured and brilliant.

The two arias from Grétry’s Silvain and

Lucile (trs. 8-9) are premiere recordings. In particular

the second of them, Au bien supreme, is an enchanting,

inward lament that I’m sure I will want to hear again.

Gluck’s Sacre piante from the one act serenata

Il parnaso confuso (libretto by Metastasio) (tr. 10)

is another lovely song, maybe at 10 minutes overlong, but Ms

Karg embellishes the repeats tastefully. The dramatic In

mezzo a un mar crudele from Telemaco (tr. 11) with

lots of fearless coloratura is a third first time recording.

It is tremendously sung: well worth hearing both for the power

of Gluck’s writing and the stunning singing.

Lucio Silla, first performed in Milano on 26 December

1772 has its fair share of routine music but there are enough

highlights to make it the best of the operas Mozart wrote in

Italy. Osborne says that the recitative and aria heard here

(trs. 12-13) ‘are both the dramatic climax and musical

peak of the opera. The long accompanied recitative, in its vivid

projection of the drama, anticipated the Mozart of Don Giovanni

while the aria, an andante in C minor, and the only minor

key aria in the opera, possesses an emotional maturity and musical

confidence which would be astonishing even if it were not composed

by a youth of seventeen.’

The final aria, Adieu from Iphigénie en Aulide

is one of the masterpieces of 18th century opera

and it is a worthy conclusion to a collection of rarities sung

by a remarkably well endowed singer, who seems cut out for a

great career. Don’t miss this disc.

Göran Forsling

|

|