|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

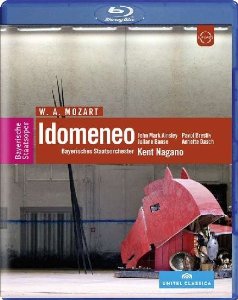

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756-1791)

Idomeneo - a music drama in three acts K366 (1781)

Idomeneo, King of Crete - John Mark Ainsley (tenor); Idamante, his

son - Pavol Breslik (tenor); Ilia, Trojan princess, daughter of

Priam - Juliane Banse (soprano); Electra, princess, daughter of

Agamemnon, king of Argos - Annette Dasch (soprano); Arbace, confidante

of the king - Rainer Trost (tenor); High Priest of Neptune - Guy

de Mey (tenor)

Idomeneo, King of Crete - John Mark Ainsley (tenor); Idamante, his

son - Pavol Breslik (tenor); Ilia, Trojan princess, daughter of

Priam - Juliane Banse (soprano); Electra, princess, daughter of

Agamemnon, king of Argos - Annette Dasch (soprano); Arbace, confidante

of the king - Rainer Trost (tenor); High Priest of Neptune - Guy

de Mey (tenor)

Chorus and Orchestra of the Bavarian State Opera/Kent Nagano

Stage Director: Dieter Dorn; Stage and Costume Design: Jürgen

Rose

rec. live, Cuvilliés Theatre, Munich, 11, 14 June 2008

Directed for TV: Brian Large

TV format: 1080i; Full HD, 16:9. Sound format: PCM stereo. DTS-HD

Master Audio surround sound

EUROARTS

EUROARTS  2072444 [176:00]

2072444 [176:00]

|

|

|

In 1780 Mozart was greatly frustrated by the lack of opportunities

to stage his new singspiel - the one we now know as Zaide.

However, the summer brought news for which the composer had

longed. It was a commission to write a serious opera for Munich,

the new base of the Court previously at Mannheim. The new work

was to be presented in the Carnival Season of 1780-1781. The

subject chosen was Idomeneo. The composer sought leave

from the Archbishop with the Chaplain of the Archbishop’s

Court being chosen to write the libretto, much of which was

written whilst Mozart was in Salzburg.

The plot of Idomeneo tells the story of the eponymous

King of Crete and is set against the backdrop of the aftermath

of the Trojan Wars. The Trojan princess Ilia is held captive

on Crete, where she has fallen in love with Idamante, the son

of her country's long-standing enemy, Idomeneo. However, to

complete the love triangle Idamante is promised in marriage

to the Mycenaean princess Electra. On his return from Troy,

Idomeneo is caught up in a violent storm. In order to save his

life he vows to sacrifice to Neptune, the sea God, the first

living creature he encounters on land; this turns out to be

none other than Idamante, his son. Idomeneo, along with his

confidante Arbace, who is the only other person to know about

his terrible vow, tries to circumvent the sacrifice by sending

Idamante and Electra to Mycenae. Neptune is up to this and prevents

the boat from leaving by creating a storm followed by the invasion

of a sea monster that threatens Crete. In despair at his father's

behaviour towards him, Idamante decides to seek death in battle

with the monster and in that way to escape from the crisis of

conscience caused by his love for Ilia. The sea monster terrifies

the whole of Crete. In order to reassure his people Idomeneo

finally reveals the reason for Neptune's anger. To general dismay,

Idamante is led to the sacrificial altar, but at the very last

moment is saved by the voice of the High Priest of Neptune who

states that Idomeneo must abdicate and hand over power to Idamante

and Ilia.

In style Idomeneo is firmly an opera seria with recitative

and set arias and ensembles easily becoming rather static vocal

showpieces. It was a genre that Mozart did not return to again

until his last staged work, La Clemenza di Tito, ten

years later. By which time, vastly more experienced, he was

able to bend the traditional form of the genre to better encompass

the dramatic thrust of the work. In Idomeneo this ability

is less evident and whilst some claim it to be equal to Tito,

the great Da Ponte trilogy of the 1780s and the singspiels Die

Entführung aus dem Serail and Die Zauberflöte,

it is perhaps better considered as being the first of Mozart’s

truly great stage works. Mozart did make revisions for performances

in Vienna in 1786 and which involved the casting of the role

of Idamante for tenor instead of the castrato of the original.

This change is compounded here with the roles of Arbace and,

unusually, the High Priest of Neptune also being sung by tenors.

The work was premiered on 29 January 1781 in the small Court

Theatre in Munich. That theatre now bears to name of the Cuvilliés

Theatre after its builder. It is in this small delightful rococo

restored venue that this performance was recorded, the staging

presented to celebrate its re-opening after three years of restoration.

Seating just over five hundred it is, economically, unlikely

to be staged in such a small venue again. In the circumstances

it is a pity that the Bavarian State Opera did not follow the

example of the Maryinsky Theatre in 1998 who for their performances

of the 1862 original version of Verdi’s La forza del

destino reconstructed the original sets (see review).

The designer here, Jürgen Rose, follows something of the

current trend of minimalism with a stage workshop set with contemporary

accoutrements. His costumes are something of a mishmash of styles

and periods that are no aid whatsoever in helping to determine

who is who when the chorus perform.

The name part has drawn many famous tenors to the recording

studio including those not noted in Mozart in the theatre, including

Pavarotti and Domingo. John Mark Ainsley’s tenor is not

of the same mellifluous character or vocal grace as those famous

names. There are some dry patches in his voice and it lacks

a free heroic ring. Nonetheless, his act two Fuor del mar

(CH.24) is a histrionic tour de force. What he brings

to the whole performance is a dramatic commitment and involvement

that overcomes the restricted setting and vocal as well as costume

limitations. Vital for any dramatic realisation to escape this

tawdry staging is that Ainsley’s strengths are matched

by the soft-grained eloquent tenor singing of Pavol Breslik

as Idamante. The duet between father and son is the particular

and most significant highlight of this performance (CHs.31).

Apart from the singers mentioned the general standard is mediocre.

Rainer Trost as Arbace, gets both his arias (CHs.20 and 42)

but now has significant raw patches in his tone and is unable

to make any impact in this production. He looks foppish and

plain silly carrying Electra’s suitcases around! Of the

ladies, Juliane Banse as Ilia starts better than she finishes

whilst the tall and imposing scarlet-gowned Electra of Annette

Dasch barely whips up a tantrum as she is left alone from the

festivities (CH.51). In the pit Kent Nagano does not come over

as particularly adept in this music which at times not only

fails to sparkle but sounds positively turgid. This turgidity

would be fatal but for the committed histrionic performances

of John Mark Ainsley and Pavol Breslik.

Robert J Farr

|

|