|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

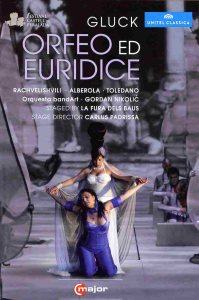

Christoph Willibald GLUCK (1714-1787)

Orfeo ed Euridice - Opera in Three Acts (1762)

Orfeo - Anita Rachvelishvili (alto); Euridice - Maite Alberola (soprano);

Amore - Auxiliadora Toledano (soprano)

Orfeo - Anita Rachvelishvili (alto); Euridice - Maite Alberola (soprano);

Amore - Auxiliadora Toledano (soprano)

Palau de la Musica Catalana Chamber Choir

Orquesta bandArt/Gordan Nikolic (violin)

Staged by La Fura dels Baus.

Director: Carlus Padrissa

Costume designer: Aitziber Sanz. Lighting designer: Carles Rigual

rec. live, Castell de Peralada Festival, 2011

Format: NTSC; Picture 16:9, HD. Sound DVD: DTS 5.1, PCM Stereo

Booklet: English, German, French

Subtitles: Italian (original language), English, German, French,

Spanish, Chinese, Korean

UNITEL/CLASSICA C MAJOR

UNITEL/CLASSICA C MAJOR  710308 [110:00]

710308 [110:00]

|

|

|

Most great composers reach a stage in their creative output

when they recognise that what they had created was a mere staging-post

in their possibilities and aspire to move the genre forward.

Think Beethoven and his Third Symphony or Rossini as he approached

William Tell and then laid down his operatic pen. Verdi,

in his long compositional life was to experience two such periods.

The first came between the third act of Luisa Miller,

along with Stiffelio, and the subsequent Rigoletto

when he took giant leaps in dramatic musical complexity and

character delineation in his operas. The second came with his

penultimate work, Otello, with its move away from the

set-pieces of the preceding Aida into a more seamless

style with the music moving the drama forward in a stream of

dramatic creativity uninterrupted by the norm of style in which

he had previously written.

The situation with Gluck was not much different than that with

his illustrious successors. He had become frustrated by the

static nature of the genre as is well illustrated in the treatment

of the Orfeo theme, one of the most durable of operatic

themes. It is the basis of Monteverdi’s work of that name

which many consider the very first opera worthy of staging.

Gluck’s version came over 150 years later. In the meantime

the genre of opera had grown massively and evolved its own rather

static conventions.

With his version of Orfeo, and in subsequent works, Gluck

consciously sought to break away from those static conventions

of recitative and aria, which focused attention on the singers

at the expense of the music and drama of the piece. These works

became his so-called reform operas. Working closely with his

librettist Calzabigi (1714-1795) Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice

was created with carefully constructed scenes. It introduced

dances and chorus to give ‘the language of the heart,

strong passions, interesting situations and constantly varied

spectacle’. This instead of the static ‘flowery

descriptions, superfluous comparisons and sententious, cold

moralising’ of what had gone before. In my view these

objectives were magnificently realised in this wonderfully melodic

and dramatically taut work. Its structure is such as to have

drawn Berlioz and Wagner to make revised editions.

So far so simple. Gluck, however, cast a contralto castrati

as his Orfeo for the first production in Vienna on the 5 October

1762. But the age of the castrati, the great primas of Handel’s

operas, was drawing to a close. They had not been acceptable

in France where a form of high tenor had evolved. For the work’s

premiere in Paris in 1774 Gluck re-wrote the role of Orfeo for

this high tenor voice. He also, like Verdi and Wagner later,

had to provide additional ballet music for the Paris performance.

Other performances and recordings, particularly in the past

fifteen years or so, have reverted to period instruments. These

have also involved the singing of the role of Orfeo by a counter-tenor

or falsettist with no use of vibrato by soloists or orchestra.

The problem with most counter-tenors is that whilst they are

strong at the top of the voice they often lack strength lower

down their range. The contralto castrato at the premiere had

a range of three octaves. Some female contralto singers such

as Ewa Podles, the Orfeo on the Arts CD, have a similar range

up to a brilliant top C. Such singers are few and far between.

Anita Rachvelishvili in this performance, whilst having rich

timbres in her lower voice is not yet of their number.

However, that is to jump ahead somewhat. The first matter is

to address the raison d’être for this performance

which influences the basis of its unique, even idiosyncratic,

character. The performance and staging is by the theatre collective

La Fura dels Baus under the direction of Carlus Padrissa

and was presented at the 25th Peralada Festival, Spain, 2011.

The costumes are modern and accompanied by a very basic set

dominated by a large vertical slab. The scenic effects are dominated

by a constantly changing series of projections, so many as sometimes

to disturb concentration on the music and singing and often

barely relevant to the story, or at least so to my eyes. A further

idiosyncrasy is the presence of at least some of the orchestra

on the stage, often moving about and becoming involved in the

action of the story and whilst playing their instruments. They

are costumed in what looks like body stockings with black vertical

stripes running their length. The stage musicians are at first

dominated by the strings and for a few moments I thought them

a period band. The strange and fractured acoustic seemed to

betray other facts and greater numbers.

Orfeo is dressed in what appears to be a low cut blue trouser

suit; so low-cut as to reveal two ample denials of masculinity.

Add a long flowing hairstyle more suitable to Carmen

and gender confusion could take over. Euridice is dressed in

a magnificent white low-cut ball gown with a décolleté

that would win, erm, hands down, in any Double D cup competition

around! Amor, often appearing and singing whilst suspended and

accompanied by a dancer is costumed and coutured in dominant

gold. Poor Orfeo has to climb the central pillar even as it

extends, albeit that she has a clearly visible harness in support

and which comes in handy when she later abseils down. Harnesses

abound with all three singers in the final trio (CH.43) swinging

about in cradles.

None of the solo singing is inadequate and often better than

that. It is not, however, in the style generally associated

with Gluck, pre- or post- reform! In a period of operatic performance

where minimalist staging is the name of the game, this is the

other end of the spectrum. Excessive visual distraction and

unidiomatic musical accompaniment leave it in a musical fashion

world of its own that may appeal to some non-Gluckian opera

lovers. The advertising blurb notes that this is the first Orfeo

ed Euridice to appear on Blu-ray. Alternative visual performances

of this great work are strictly limited. Despite its over-luxurious

orchestration, stick with that under Raymond Leppard and Janet

Baker or wait until some enterprising company gets Ewa Podles

and a period band together under a conductor immersed in the

idiom.

Robert J Farr

see also review (of Blu-ray version) by Kirk

McElhearn

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews