|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS |

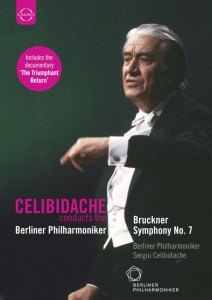

Anton BRUCKNER

(1824-1896)

Symphony No. 7 in E major (1881-1883) (1885, ed. Haas) [90:00]

Berliner Philharmoniker/Sergiu Celibidache

Berliner Philharmoniker/Sergiu Celibidache

rec. live, 31 March-1 April 1992, Schauspielhaus, Berlin

Documentary: The Triumphant Return [54:00]

Directors: Rodney Greenberg (concert), Wolfgang Becker (documentary)

Picture: 16:9, 1080i Full HD. Documentary: 4:3

Sound: PCM Stereo only

Subtitles: German, English, Japanese

Region: all (worldwide)

EUROARTS 2011404

EUROARTS 2011404  [90:00 + 54:00]

[90:00 + 54:00]

|

|

|

Celibidache’s near legendary Bruckner recordings have

a chequered history; Deutsche Grammophon’s Stockholm and

Stuttgart cycle from the 1960s and 1970s was quite widely available,

but Sony’s Munich videos ran into legal problems and were

recalled soon after their release on LaserDisc and VHS. As for

the later - audio-only - Munich recordings, these are now available

in a reasonably priced EMI box. Delving into the background

to this 1992 Berlin Seventh I was surprised to find several

CD and DVD issues from obscure - presumably ‘pirate’

- labels; Sony also released this on LD and VHS.

As with the Munich Philharmonic Eighth, I first encountered

Celibidache’s Seventh - the live recording from Tokyo

- while channel-hopping late one night; I may not have heard

it all, but I came away from this transfiguring event a convert.

Celi’s expansive - some would say sprawling - way with

both scores defies musical logic; at these speeds they really

ought to crash and burn, and yet they have a lift and loftiness

I’ve not encountered anywhere else. If that Tokyo Seventh

could take wing at all, then this Berlin one would surely soar.

There’s a history behind this concert, outlined in the

accompanying documentary. I’ll comment on that after the

performance, as there are some technical issues that need to

be aired right away. This concert was filmed in 4:3, the roughly

square picture we remember from our CRT days, but Euroarts have

decided to mimic widescreen - 16:9 - by masking the picture

at top and bottom. I doubt anyone with even a modicum of interest

in this event would welcome the change, as it results in heads

being ‘chopped off’. Thankfully the documentary

has been left in its original format, and I suppose we must

be grateful no attempt was made to synthesise a surround audio

mix as well.

Then there’s the question of performing editions. Bruckner’s

1883 score only exists as an amended autograph; Gutmann’s

1885 score was thought to include unauthorised alterations by

the conductor Artur Nikisch and others. The Haas edition of

1944, which uses some of the original - albeit compromised -

1883 score, is a valiant attempt to get back to the composer’s

first thoughts. That said, he omits the cymbals, triangle and

timps from the Adagio, something that Celi - who’s wedded

to Haas in this symphony - reinstates.

Faith is an unfashionable subject in this secular age, yet it’s

almost impossible to hear this music without being keenly aware

of this composer’s abiding humility. From the simple surrender

of those opening bars to the charm at its dancing heart and

the unfurling grandeur of its close this Allegro is truly divine.

Celi is measured but not rhetorical, and the music is allowed

to move and breathe in the most natural way. The all-important

blend and balance that creates those echt-Brucknerian

sonorities is there too; what a noble vintage compared with

the acidulous plonk of Franz Welser-Möst’s recent

Bruckner Eighth (review).

The HD picture - upgraded from the standard-def original - is

pretty sharp and the colours are true. More important the sound

has a penetrating warmth that ravishes the ear and batters the

heart. The horns and brass are especially well caught, and there’s

some wonderful flute playing too. Günter Wand’s live

Berlin account for RCA - recorded in 1999 - has similar amplitude

but it has harder edges and more thrust; by contrast, Celibidache

finds a degree of inwardness and vulnerability here that’s

deeply affecting. And in the movement’s final, multilayered

peroration - where the music ‘gathers to a greatness’,

as Hopkins would have it - Celi is sans pareil.

The Berliners surpass themselves too, playing with a commitment

and passion that’s rare these days. There’s a lyrical

intensity and singing line in this Adagio that will take your

breath away, and those dark, plangent brass chorales would make

the angels weep. At times this band sounds like a giant chamber

group; they’re alive to the subtleties of internal balance

and move seamlessly from one long-breathed phrase to the next.

It really is a wonder to behold, with every strand of this great

score laid bare in the most convincing and organic way. It’s

a long movement, and there is a hint of longueurs towards

the end, where even the camera’s eye is tempted to rove

the hall.

Really, that’s a small price to pay for music-making of

this calibre, aided and abetted by sound of astonishing range

and fidelity. Indeed, the sonics here are among the very best

I’ve encountered on Blu-ray, and they put some recent

discs to shame. Every timbre is most faithfully rendered, each

fragment heard without recourse to the kind of audio trickery

that mars so many filmed concerts. Rodney Greenberg’s

direction is invariably discreet and well-informed; in fact

it’s a model of its kind, with only the compromised framing

a reminder of that dubious decision to go wide.

The tally-hoing trumpets and canter of the Scherzo are nicely

done. Remarkably, Celi still looks as fresh as an alpine flower,

although the orchestra - the brass especially - do sound a little

tired. And not even this gifted maestro can hide the joints

and seams of the Finale, which so often makes me think of a

revivalist preacher entangled in his own fiery rhetoric. That

said, this is still a noble, stirring Seventh, and I doubt we’ll

hear its like any time soon. Given the prolonged applause and

heartfelt cheers I’d say the audience agrees.

I usually have to force myself to watch these ‘bonus tracks’,

but this hour-long feature by Wolfgang Becker is more illuminating

than most. It dips into Celi’s career with the orchestra

after the war and hints at the politics that separated them

in the 1950s. The archive footage shows a young man of flamboyance

and gypsy good looks who also had quite a temper. Much of Becker’s

film is dedicated to conversations with older members of the

band and rehearsal clips for the Berlin Seventh.

It’s a measure of this conductor’s forensic understanding

of the score - not to mention the Berliners’ collective

skill - that this music can be so carefully picked apart and

reassembled with such precise and astonishing results. There’s

little sign of ill temper here, except for parade-ground barks

of ‘Firsts!’ and ‘Seconds!’, with many

images of an ageing maestro prone to gentle philosophising.

In that sense this is a telling - and affectionate - portrait

of a man in his twilight years, yet still possessed of a riveting

intellect and powerful podium presence. Now if only all ‘extras’

were this interesting.

A uniquely satisfying Seventh; a must for all Brucknerians.

Dan Morgan

http://twitter.com/mahlerei

see also review of DVD release by John

Whitmore

Masterwork Index: Bruckner

7

|

|