|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

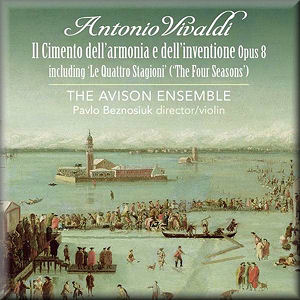

Antonio VIVALDI (1678 -

1741)

Il Cimento dell'armonia e dell'inventione Opus

8

CD 1

Concerto in E, op. 8,1 'La Primavera' (RV

269) [10:21]

Concerto in g minor, op. 8,2 'L'Estate'

(RV 315) [10:25]

Concerto in F, op. 8,3 'L'Autunno'

(RV 293) [10:17]

Concerto in f minor, op. 8,4 'L'Inverno'

(RV 297) [8:25]

Concerto in E flat, op. 8,5 'La Tempesta di Mare'

(RV 253) [9:13]

Concerto in C, op. 8,6 'Il Piacere' (RV 180)

[9:09]

CD 2

Concerto in d minor, op. 8,7 (RV 242) [8:12]

Concerto in g minor, op. 8,8 (RV 332) [9:47]

Concerto in d minor, op. 8,9 (RV 454) [8:06]

Concerto in Bes, op. 8,10 'La Caccia' (RV

362) [8:34]

Concerto in D, op. 8,11 (RV 210) [12:27]

Concerto in C, op. 8,12 (RV 449) [9:04]

The Avison Ensemble/Pavlo Beznosiuk (violin)

The Avison Ensemble/Pavlo Beznosiuk (violin)

rec. 29 November - 5 December, St George's Chesterton, Cambridge,

UK. DDD

LINN RECORDS

LINN RECORDS  CKD

365 [57:54 + 56:16] CKD

365 [57:54 + 56:16]

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

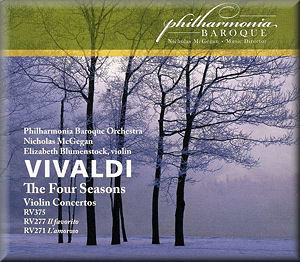

Antonio VIVALDI (1678 -

1741) The Four Seasons - Violin Concertos

Concerto in E, op. 8,1 'La Primavera' (RV

269) [9:29]

Concerto in g minor, op. 8,2 'L'Estate'

(RV 315) [9:53]

Concerto in F, op. 8,3 'L'Autunno'

(RV 293) [10:10]

Concerto in f minor, op. 8,4 'L'Inverno'

(RV 297) [8:15]

Concerto in B flat (RV 375) [13:55]

Concerto in e minor 'Il favorito' (RV 277)

[13:33]

Concerto in E 'L'amoroso' (RV 271)

[10:11]

Elizabeth Blumenstock (violin)

Elizabeth Blumenstock (violin)

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra/Nicholas McGegan

rec. 9 - 11 December 2010, Skywalker Sound, Nicasio, CA, USA. DDD

PHILHARMONIA BAROQUE PRODUCTIONS PBP-03 [75:30]

PHILHARMONIA BAROQUE PRODUCTIONS PBP-03 [75:30]

|

|

|

Comparison: Montanari/Dantone (Arts)

Many of Vivaldi's concertos bear titles. They are sometimes

referred to as 'programme music', but that is

mostly incorrect. There is a difference between 'programme

music' and 'descriptive music'. The former

has a story line or illustrates a sequence of events, whereas

the latter only depicts a phenomenon or an emotion. To make

things even more complicated: many pieces of the baroque era

are descriptive, even though they bear no titles at all. Most

of Vivaldi's concertos with titles belong to the category

of 'descriptive music', like la notte

(the night) or la tempesta di mare (the storm at sea).

The Concerto in E 'L'amoroso'

(RV 271) which is included in the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra's

disc is an example of a concerto which refers to an emotion.

The Four Seasons are without any doubt the most famous

of all Vivaldi's concertos. They were already famous

in Vivaldi's own time, immediately after being printed

in 1725 as part of the twelve concertos Op. 8. There can be

no doubt about their programmatic character, because Vivaldi

added four sonnets describing the features of the various seasons.

In order to leave no doubt about his intentions he added precise

indications about the meaning of various effects in several

of the concerto's parts.

It is notable that neither the sonnets nor these indications

were part of these concertos at the onset. The Op. 8 was dedicated

to the Bohemian count Morzin who had honoured Vivaldi with the

title maestro di musica in Italia. The composer had

sent the Four Seasons to the count some time before

1725 or probably performed them in his presence. In his preface

he writes: "I beg Your Highness not to be astonished at

finding among these few feeble concertos The Four Seasons,

which met with Your Highness's indulgent approval so

many years ago; believe me, I found them worthy of being printed

- although in every respect they are the same pieces - because

on this occasion I have added not only the sonnets but also

precise explanations on all the things that are depicted here."

It seems that he didn't want to create any misunderstandings

about the meaning of these concertos now that they could be

played by others than himself.

There are many recordings of these four concertos in the catalogue.

They are mostly performed independently, without the other eight

concertos of the Op. 8 set. Those who only want to have the

Four Seasons will probably not purchase a recording

of a whole set. That is a shame as the other concertos are not

in any way inferior to these four. Anyway, that makes it less

useful to compare the recording of The Avison Ensemble with

other recent recordings of the Four Seasons. I have

therefore chosen the recording of the complete set by Stefano

Montanari and the Accademia Bizantina, directed by Ottavio Dantone,

released with the concertos Opus 3 by Arts.

I was generally enthusiastic about their performances, even

though I find the size of the ensemble, including seven violins,

debatable.

In comparison I have strong reservations about both recordings

reviewed here. The Avison Ensemble and the Philharmonia Baroque

Orchestra (PBO) are even larger than the Accademia Bizantina,

with 9 and 11 violins respectively. It is not easy to decide

what the common size of instrumental ensembles in Vivaldi's

time was. The orchestra of the Ospedale della Pietą allowed

larger scorings than one instrument per part. That was probably

the exception. What is more important is the relationship between

the solo instrument and the tutti. Whatever the size of the

instrumental body, the soloist is always primus inter pares;

solo concertos of the baroque era are ensemble pieces, not -

as in the romantic era - for a soloist and an orchestra. In

PBO's recording Elizabeth Blumenstock is too much in

front of the orchestra and seems even not to be part of it.

In comparison, Pavlo Beznosiuk is more integrated in the ensemble.

What these two recordings have in common is a lack of transparency.

That is due not only to the size of the orchestras: the performance

of the Accademia Bizantina is clearly better in this respect.

There is little to choose between the performances of Pavlo

Beznosiuk and Elizabeth Blumenstock. Both are fine violinists

and have no technical problems in realizing the demanding solo

part. Some effects come off better in one performance, others

in the other. Let me just mention a couple of things. Both interpretations

of the first concerto are too tame. Blumenstock depicts the

bird singing in the first movement better than Beznosiuk. Not

much is made in either recording of the repeated notes in the

second movement which are a depiction of the barking of the

shepherd's dog. In the last movement both violinists

fail to illustrate the dancing of nymphs and shepherds.

The second concerto is rather well done by both, but Beznosiuk

makes the most of the imitation of cuckoo, turtledove and goldfinch

in the first movement. The cuckoo is virtually inaudible in

Blumenstock's performance. The threatening atmosphere

in the second movement is also slightly better with Beznosiuk,

partly due to his slower tempo.

The first movement of the third concerto describes the dance

and song of the peasants. It is notable that Beznosiuk plays

it largely legato. It reminds me of the sound of the musette,

often associated with the countryside. Was that the thought

behind this decision? Ms Blumenstock plays it more like dance

music, but she makes a bit too heavy weather of it. The last

movement is a hunting scene, and at the end the prey dies. I

particularly like the way the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra

plays the last phrase piano: the music dies with the prey.

The last concerto is the least satisfying in both performances.

The first movement lacks subtlety. There is more to it than

both suggest as Stefano Montanari's recording shows.

The falling raindrops come off better in Beznosiuk's

interpretation than in Ms Blumenstock's. The latter movement

is again most differentiated with Montanari. In the first movement

of this concerto the distance between the solo violin of Elizabeth

Blumenstock and the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra is all too

obvious and here it is more of a problem than elsewhere.

There is no one way to perform these concertos. Nowadays we

are used to hearing them in rather theatrical recordings by

Italian ensembles. Sometimes they tend to exaggerate, as I recently

observed while listening to an almost caricature-like performance

by Forma Antiqva (Winter & Winter, 2012). Beznosiuk and

Blumenstock are more or less at the other side of the spectrum,

and reflect the more restrained Anglo-Saxon approach. Despite

the size of the ensemble Montanari and Dantone seem to have

found an approach which is just right, being theatrical and

evocative, but still observing the baroque ideal of balance

and good taste.

The Avison Ensemble also offers the other eight concertos from

Op. 8. Here again I prefer the Accademia Bizantina, especially

because of better articulation, a more relaxed way of playing

and a more differentiated treatment of the notes and of dynamics.

For the concertos 9 and 12 Vivaldi has indicated the oboe as

the alternative for the violin. Dantone has given them to the

oboe, in Beznosiuk's performance they are played by the

violin. It would have been nice to have them in both versions

- there was enough space left on both discs.

The PBO's recording includes three other violin concertos.

The performances are rather good, but the size of the ensemble

and the position of the solo violin in the ensemble is problematic

once again. The recording of the concertos RV 271 and 277 by

Enrico Casazza and La Magnificą Comunita is much more an ensemble

effort with the violinist acting as part of the body of strings

(review).

To sum up: both recordings have nice things to offer, but they

fall short in fully exploring the character of Vivaldi's

concertos.

Johan van Veen

http://www.musica-dei-donum.org

https://twitter.com/johanvanveen

|

|