|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Download

from The Classical Shop

|

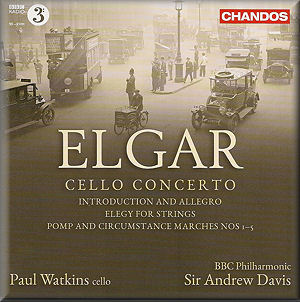

Sir Edward ELGAR (1857-1934)

Cello Concerto in E minor, Op.85* [26:30]

Introduction and Allegro for String Quartet and String Orchestra,

Op.47** [14:56]

Elegy, Op.58, an Adagio for String Orchestra [3:55]

Military Marches ‘Pomp and Circumstance’, Op.39/1-5 [28:58]

Paul Watkins (cello)*; Daniel Bell (violin), Steven Bingham (violin),

Steven Barnard (viola), Peter Dixon (cello)**

Paul Watkins (cello)*; Daniel Bell (violin), Steven Bingham (violin),

Steven Barnard (viola), Peter Dixon (cello)**

BBC Philharmonic/Sir Andrew Davis

rec. 4-5, 7-9 October, 2011,

MediaCity UK, Salford. DDD

CHANDOS CHAN10709 [74:44]

CHANDOS CHAN10709 [74:44]

|

|

|

Paul Watkins is nothing if not energetic. He already combines an international career as a solo cellist with a busy schedule of conducting and membership of the Nash Ensemble. Shortly he is to join the renowned Emerson Quartet and, if I recall correctly a recent interview he gave on BBC Radio 3, he will accommodate that new appointment by leaving, with regret, the Nash Ensemble. However, I think he intends to continue conducting and, of course, making solo appearances as a cellist. That’s good to hear because we wouldn’t wish to lose from the concerto circuit someone who can play the Elgar concerto as well as he does on this CD

His partnership on this recording with Sir Andrew Davis represents something of a reunion for Watkins was principal cellist in the early 1990s with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and he would have worked extensively with Sir Andrew at that time during Davis’s time as the distinguished Chief Conductor of the orchestra. It probably helps that they know each other‘s ways quite well – Davis conducted a lot of Elgar during his time at the BBC – and Watkins is quite right to pay tribute, in a short personal note in the booklet, to Davis’s stature as an Elgar conductor.

In that same note Watkins makes a comment that I find even more interesting. Referring to the cello on which he plays, an Italian instrument made in about 1730, he says this: “This instrument has, I feel, the perfect voice for this piece – the combination of burnished woody timbres and a plangent expressivity, reminiscent, perhaps, of an English tenor voice.” The italics are mine. I find that a fascinating and very insightful comment. Of course, in this concerto the cello is often taken far lower than the compass of the tenor voice and down into baritone or even bass territory. Nonetheless, the comparison is one I’ve not heard before and it’s one that, on reflection, I find very apt.

Brian Wilson was very impressed by this new version of the Cello Concerto, when he reviewed the download version, even if the merits of this performance could not shake Mrs. Wilson’s aversion to the work. As Brian indicated, the newcomer is a good deal less intense than the celebrated du Pré/Barbirolli performance. Like many other people, I’m sure, I came to know the work through that 1960s recording and it remains very special. However, I know what Brian means about the intensity of the reading; between them, du Pré and Barbirolli plumb depths of emotion that are truly remarkable but theirs is not the only way with the concerto and though I still cherish that recording I can sympathise with – and respect – those who find it a bit too much to take.

I think I’d describe this Paul Watson performance as objective and direct. That’s not to suggest for one moment that either he or his conductor skate over the emotional surface of the work; on the contrary, there’s a fine amount of feeling in the performance. On the other hand, anyone who finds the du Pré traversal veering dangerously towards self-indulgence will, I feel, be much happier with Watkins’ balanced approach. I liked the nice lilt that he and Davis impart to the second subject in the first movement and, indeed, I think their account of this movement as a whole is a conspicuous success. The quicksilver music in the second movement is done with panache. The Adagio is the beating heart of the work and Watkins and Sir Andrew bring out the poignancy and pathos of the music. However, everything is satisfyingly in proportion and the pace seems just right. It’s interesting to note that this present performance lasts for 4:21 whereas du Pré takes 5:15. It may be objected that one minute is neither here nor there but in such a short movement it’s quite a significant difference. The new recording is topped off by an excellent account of the finale in which I admired especially the reminiscence of the third movement; here that passage is handled most sensitively. So, anyone wanting a recording of the Cello Concerto can invest with confidence. What of the remainder of the programme?

Davis offers something of a mixed bag of Elgar pieces but he’s successful in all of them. Elgar himself described the Introduction and Allegro as a ‘Big Piece’ and that’s just how it’s played here. All the feeling in the piece is well brought out – the ‘Welsh tune’ episode just before the start of the fugue, for example – but overall this is a muscular, strongly projected performance, which I enjoyed very much indeed. When the fugue starts (track 6, 3:52) the articulation is crisp and clean and Davis builds the fugue excitingly. The strings of the BBC Philharmonic are in prime form and the solo quartet, comprised of the orchestra’s section principals, do an excellent job. One thoughtful presentational point is worth noting: Chandos splits the piece into two tracks, namely the Introduction (3:42) followed by the Allegro (11:12). The other string work couldn’t be more different. The little Elegy is a gorgeous miniature and, as Anthony Burton says in his useful notes, it is cast in “Elgar’s characteristic vein of elevated, restrained grief.” This performance is beautifully judged.

If the Elegy shows us the intimate side of Elgar – and of Sir Andrew Davis as an Elgar conductor – the public face is very much on display in the five ‘Pomp and Circumstance’ marches. These are classics of the genre and, of course, there’s much, much more to them than ‘Land of Hope and Glory’. Davis must have conducted No 1 at the Last Night of the Proms on many occasions and with suitable gusto. Here he’s able to present the piece in a somewhat straighter fashion and when the Big Tune first appears (1:55) he finds just the right amount of noble restraint. When, at the end of a super performance, the tune is reprised in all its glory the organ makes its presence felt: was this dubbed in, I wonder? The other marches are done very well too. Davis plays No 2 with thrust and swagger and realises the strange, almost nocturnal stretches of No 3 very well. I’ve always had a soft spot for No 4, probably because it was the first Elgar I ever played – our school orchestra played it before we tackled No 1 – and the trio tune is rather splendid. Elgar may have regarded the trio of No 1, correctly, as a once-in-a-lifetime-tune but he came pretty close to repeating the feat in No 4. The fifth march was written much later than its four predecessors – in 1930 – and in it we get a last glimpse of the seemingly confident, public side of Elgar. The jaunty rhythms are crisply delivered in this performance and, as we don’t hear this march all that often it’s good to be reminded that it too has a pretty good trio tune.

This is an excellent disc which I’ve enjoyed greatly. The playing of the BBC Philharmonic is excellent, reminding us – if we needed to be reminded – that Manchester has two first class symphony orchestras. They’re directed and energised by one of the leading Elgar conductors of the present moment. Add to that a splendid soloist in the Cello Concerto and you have a distinguished release. The performances are reported in excellent Chandos sound, which has all the presence and detail that one expects from this label. Incidentally, this is the first CD I’ve heard from the BBC Philharmonic since they moved into their new home at MediaCity UK in Salford. The name of the new venue may be dreadful but it seems that the studio in which the orchestra now plays produces good results. I have the impression, on a first hearing, that the acoustic is somewhat more ample than was the case in their former home at Studio 7, New Broadcasting House, where the sound was very immediate. In the new venue there appears to be a bit more space around the sound of the orchestra.

John Quinn

See also download review by Brian Wilson

|

|