|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

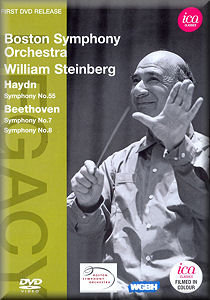

Joseph HAYDN

(1732-1809)

Symphony no.55 in E flat Hob.I/55 [21:54]

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Symphony no.7 in A op.92 [37:55]

Symphony no.8 in F op.93 [26:07]

Boston Symphony Orchestra/William Steinberg

Boston Symphony Orchestra/William Steinberg

rec. 7 October 1969 (Haydn), 6 October 1970 (sy 7), 9 January 1962

(sy 8), Symphony Hall, Boston (Haydn, sy 7), Sanders Theatre, Harvard

University (sy 8)

ICA CLASSICS

ICA CLASSICS  ICAD 5067 [86:00]

ICAD 5067 [86:00]

|

|

|

For most record collectors the name of William Steinberg is

synonymous with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, of which

he was musical director from 1952 to 1976 and with which he

made a long series of well-considered recordings. Londoners

scarcely recall that he was Boult’s successor as principal conductor

of the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1958. Ill-health ended

what may have been a promising association in 1960.

Illness also prevented his conductorship of the Boston Symphony

Orchestra (1968-1972) from becoming more than a hiatus. As Richard

Dyer’s notes – a welcome recurring feature of this series –

tell us, the period in question was more notable for the opportunities

his cancellations offered to his young assistant Michael Tilson

Thomas.

Steinberg’s appointment to Boston came at a time of low morale

for the orchestra. Leinsdorf’s period had not worked out, for

reasons not readily explained by the video material emerging

in this series. Great things had been expected of Steinberg,

who had been assistant to both Klemperer and Toscanini and was

famed as an orchestra builder. It is therefore interesting to

have at least one early colour video of him in action with the

orchestra during his tenure, plus a guest appearance from somewhat

earlier, filmed in black and white. What it doesn’t explain

is why anyone should have thought he could do anything Leinsdorf

couldn’t. Both, after all, were eminently straightforward interpreters

with a strong eye for orchestral discipline. Nearly fifty years

on it is Leinsdorf who seems to have had the more enquiring

mind and – at least often enough for it to be worth keeping

him on – the ability to create a sense of occasion. Possibly

the contrast between Leinsdorf’s acerbic wit and what Dyer describes

as Steinberg’s “pipe-smoking geniality” carried more weight

with good Bostonian society that the actual performances.

Steinberg’s movements were famously minimalist. However, like

many conductors of an earlier generation, he used a longish

baton and presumably expected the players to follow the tip

of it, rather than his arm movements. Looked at this way his

stick is actually both energetic and vital. I was curious to

note that, when beating three-time, his second beat goes to

his left, rather than to the right as is more usual. This can

be seen very clearly at the beginning of the Haydn. No doubts

about his clarity, however.

Steinberg’s four performances of Haydn’s Symphony no.55 in 1969

are apparently the only ones the orchestra has given of this

work. Unlike Munch conducting no.98 in 1960, Steinberg has a

harpsichord, particularly active in the slow movement. This

sounds big-band Haydn today but is slimmed-down by the light

of its times. It’s all very neat, buoyant and nicely phrased.

The Beethoven symphonies are resolved with swift tempi, clean

textures and clear phrasing. The effect is again buoyant rather

than driven. Many conductors who take the first movement of

no.7 swiftly are unable to maintain proper articulation of the

dotted rhythms right through. The beginning of the development

is a danger point where even Reiner falters. Steinberg is one

of the best I’ve heard from this point of view.

But, having admired the performances for their avoidance of

pitfalls, I still can’t help feeling that the Boston Symphony

Orchestra under its music director ought to have offered something

more. There was a greater distinction in the public view back

then between the “big five” American orchestras and all the

others, good as many of them were. Pittsburghers had every reason

to be proud of having such a tip-top bandmaster for over two

decades. Impecunious record collectors in the UK who got to

know Beethoven symphonies through Steinberg’s Pittsburgh recording

as issued on Music for Pleasure had cause for gratitude that

they could obtain such an excellent introduction so cheaply.

I am sure that Steinberg’s guest appearances with the “big five”

were justly appreciated. But did he have that something extra

you expect from the music director of one of the “big five”?

Go to Leinsdorf’s performance of the “Egmont” overture in this

same series, right at the end of his criticized reign and you’ll

hear that something extra – a Beethoven orchestra in full cry

and a conductor inspiring them, not just directing them.

I’m sure purchasers will enjoy this video, but the real revelations

of this series so far have been the Leinsdorf issues, though

I say that without having heard all the Munch ones, which are

pretty numerous.

Useful documentation of a conductor whose time with the orchestra

was short.

Christopher Howell

|

|