|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Download

from The Classical Shop

|

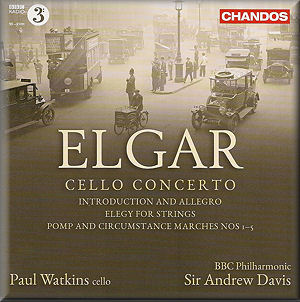

Edward ELGAR (1857-1934)

Cello Concerto in E minor, op.85 (1918-19)* [26:30]

Introduction and Allegro, Op. 47 (1904) [14:56]

Elegy, op. 58 (1909) [3:55]

Military Marches, Pomp and Circumstance, op. 39 (1901-30)

[28:58]

Paul Watkins (cello)*

Paul Watkins (cello)*

BBC Philharmonic/Sir Andrew Davis

rec. 4-5, 7, 9 October 2011, MediaCity UK, Salford

CHANDOS CHAN10709[74:44]

CHANDOS CHAN10709[74:44]

|

|

|

Mention Elgar’s Cello Concerto to almost any classical

music buff worth their salt and they are more than likely to

go misty-eyed and say, ‘ah yes, Jacqueline du Pré …’ Her 1965

recording with Sir John Barbirolli on EMI is one of those very

few which has stamped its authority so firmly on any one work

that anyone following might as well put in as an ‘also-ran’

before they start. What is it about that classic EMI record?

Leaving all sentimental associations about poor Jacqueline’s

illness and early demise aside, this is a performance which

projects its emotions from the bottom upwards. Conducted by

someone who started out as a cellist and who began his career

while Sir Edward was still very much around, it’s a version

which has a special and unique intensity, and quite simply gives

another meaning to the word ‘authenticity’.

I remember Paul Watkins sitting in once at a rehearsal while

I was still blowing flute at the South Gwent Youth Orchestra

– a band which at times had more flutes and clarinets than all

of the string sections put together. He made us all feel very

ordinary, being at that time already a miniature whizz-kid and

always destined for greatness. This Chandos recording is indeed

a great achievement. The recorded balance is pretty good, though

while the orchestra has plenty of presence in the tutti passages

it doesn’t have quite the ballsy contribution which Sir John

gets from his London Symphony Orchestra forces. This is where

the intensity is at a lower level in this otherwise very fine

performance. Watkins is refined and eloquent and brings everything

you could want to the work, but you always have the feeling

the BBC Philharmonic is accompanying rather than really in competitive

dialogue: sparring with the soloist as an equal artistic entity.

Just have a listen to that first real melody which the strings

introduce in the second minute of the first movement. This is

indeed a moment which needs space in order to grow later on,

but it could have a touch more fragility that that rather matter-of-fact

way Sir Andrew Davis has it appear. I shouldn’t carp. There

are so many technical features about the way the BBC Phil plays

which are such an improvement on the old warhorse, and I’m sure

sentimental attachment has as much to do with many of our responses

as anything else ...

No? OK – let’s put aside 50 year old recordings and look afresh

at this piece. The vocal character of the cello is one of its

great strengths, and Paul Watkins does so much more than just

play the tunes. His range of colour and expression is tremendous,

and the instrument he uses he describes in the booklet as having

a “combination of burnished woody timbres and a plangent expressivity,

reminiscent perhaps of an English tenor voice.” The response

between soloist and conductor is also mentioned by Watkins,

with Sir Andrew Davis “highly skilled at reading a soloist’s

musical thoughts and enabling an orchestra to respond instantaneously.”

This is indeed a synergy which shines through in the momentary

changes and subtle little points which constantly emerge in

the second movement. The Adagio sings; creating both

a breathtaking musical landscape and the kind of aria which

would have the power to carry an opera out of all proportion

in size to its four and a half minutes’ duration. We have a

certain amount of grunting and moaning from the conductor in

the beginning of the last movement, but crisp rhythms and that

rich expressive palette from which to draw in this most substantial

of all the movements. Listening to what happens here makes you

realise how close Elgar already was to Shostakovich in his first

cello concerto. They are worlds apart, but most certainly

in orbit around the same emotional field of gravity. This is

most certainly a performance which has ‘legs’. Yes indeed, they

grow on you over time and, in this Olympic year, deliver their

own rewards.

Of the Introduction and Allegro I have no complaints,

though fans of Sir John Barbirolli will again seek that impassioned

intensity and sense of wild and tragic danger to be found in

his EMI Sinfonia of London recording. There is no blood on the

carpet with the BBC Philharmonic, but it’s still a superb thing

to have around. The Elegy is gorgeous here as well.

The BBC strings made me wonder if this was where Howard Skempton

had found his Lento, but I fear I was tilting at windmills.

Either way this is a warm and all-embracing performance to which

you will want to return.

You might wonder why anyone would want to listen to, let alone

record the ‘Pomp and Circumstance’ marches these days. Better

in musical content than most military marches, this is ostensibly

music with a function, and the only remaining function of the

grand tune of March No. 1 would appear to have would

be to stir up National Pride at the last night of the Proms

or similar. If you feel like waving a Union Flag at home in

your Union Flag underwear then this is as good a place to get

your sounds. Indeed, the March No. 1 sounds magnificent

with full organ, and the less familiar tunes are full of unexpected

associations. March No. 2 has moments which I might

easily have mistaken for something by Dvorak in days gone by,

and there’s a sense of theatre throughout which often transcends

the ‘Military March’ appellation. As an evocation of a period

when carriages were horse-drawn – and who knew that horses could

draw – the March No. 4 is hard to beat: you can sense

the pulsating energy of a time in which people actually did

and made things, rather than worked as executive administrative

financial advisory management assistants.

Seen as a musical pastie, this is a remarkably fine Cello

Concerto and string orchestra filling, with a crusty military

pastry which won’t break your teeth and is actually rather unexpectedly

fine. The BBC Philharmonic sound as if they are enjoying themselves,

and there is a vibrant sense of collective positivity in the

whole programme – even from the tragic tones of Elgar’s last

major masterpiece. With stunning recorded sound, what more could

one ask.

Dominy Clements

see also review by John

Quinn

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews