|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

|

Byways of Beecham

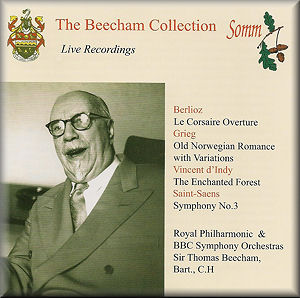

Hector BERLIOZ (1803-1869)

Le Corsaire Overture, Op. 21 [8:09]

Edvard GRIEG (1843-1907)

An Old Norwegian Folksong with Variations, Op. 51 [17:53]

Vincent d’INDY (1851-1931)

La ForÍt Enchantťe. Symphonic legend after Uhland, Op. 8* [13:42]

Camille SAINT-SAňNS (1835-1921)

Symphony No 3 in C minor, Op.78** [36:07]

Denis Vaughan (organ), Tom McCall and Douglas Gamley (pianos) **

Denis Vaughan (organ), Tom McCall and Douglas Gamley (pianos) **

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Sir Thomas Beecham

*BBC Symphony Orchestra/Sir Thomas Beecham

rec. 7 March 1951, Royal Albert Hall (Berlioz); 27 November 1955,

Royal Festival Hall (Grieg); 21 October 1951, BBC Maida Vale Studios,

London (d’Indy); 20 October 1954, Royal Festival Hall (Saint-SaŽns).

ADD

SOMM-BEECHAM 32 [76:11]

SOMM-BEECHAM 32 [76:11]

|

|

|

The Somm label has unearthed some more buried Beecham treasure

– and it’s pure gold!

This latest issue in their Beecham series will be of particular

interest to Beecham devotees because it includes two pieces

– the D’Indy and the Saint-SaŽns – of which, so far as I know,

the eminent conductor made no commercial recording. Furthermore,

though he took the Grieg piece into the studio I think the resultant

recording is, perhaps, one of his lesser known ones.

The Berlioz overture was a staple of the Beecham repertoire,

though he didn’t conduct it until 1946, according to Graham

Melville-Mason’s valuable notes. Thereafter he performed it

some sixty times and he made three recordings of it. The present

performance is full of vim and vigour – though there’s also

light and shade at the appropriate points in the score. Beecham

whips up some real excitement in this reading and the last couple

of minutes in particular are tremendous.

I have to confess that I didn’t know the Grieg at all. Mind

you, I can take a little comfort from the fact that Sir Thomas

seems to have come to it late as well; he only took it up in

1955 and, in fact, he performed it on only three occasions –

all in that year – making a studio recording in between these

live performances, of which the present one was his second.

The work in question was written in 1890 for two pianos and

the orchestral version was made between 1900 and 1905. I wouldn’t

say it’s a neglected masterpiece but it is an engaging piece

and just the sort of music that Beecham could do so well, bringing

it to life. In this performance the RPO woodwind section plays

with great finesse and the string choir is on pretty good form

too. Beecham characterises the music very nicely and the subdued,

tender ending is quite magically done.

Beecham played music by d’Indy from quite an early stage in

his conducting career and he first conducted La ForÍt Enchantťe

(1878) in 1907. Subsequently he met the composer. This particular

piece remained in his repertoire until 1951; indeed, the last

time he gave it in public – in a concert he gave with the BBC

Symphony Orchestra - was the day before he made this studio

recording, also with the BBC SO. The recorded sound is not as

good as on the other pieces in this collection, as Somm admit

in the booklet. There is some distortion at times but, nonetheless

it’s very valuable to have this unique example of Beecham in

this work. He imparts plenty of drive and is clearly committed

to the score; furthermore he’s alive to the poetic passages.

Despite the sonic limitations it was well worthwhile issuing

this performance.

It’s a little surprising, perhaps, that Beecham never recorded

the Saint-SaŽns Third Symphony, a work that one might feel to

be tailor-made for him. However, the symphony was neither as

well-known nor as popular in Beecham’s day than has subsequently

become the case. He first performed it in1913. On that occasion

the composer was present and there’s a delicious anecdote about

that performance in the booklet – for once Beecham was on the

receiving end, though he delights in telling the story nonetheless!

The symphony has its detractors but I like it, especially when

it’s given with panache and empathy, as here.

The RPO strings are in fine fettle in the first movement and

there’s also some sparkling woodwind playing to enjoy. I don’t

know why Somm don’t track the second movement separately - it

starts at track 4, 10:37. Like most conductors Beecham rather

ignores the ‘poco’ element of the Poco adagio tempo

indication and takes the solemn theme broadly, a decision that

the richness of the RPO strings vindicates. The organ is well

integrated into the ensemble sound. The recorded sound may not

be as sumptuously integrated as in a modern digital recording

but we can still enjoy a fine, affectionate performance – note

how Beecham gets the orchestra to play con amore (especially

17:46 – 19:09). The third movement is ebullient and full of

Beecham verve. The booklet notes relate how great care was taken

to get the sound of the Festival Hall organ just right and in

view of that the great chord that opens the finale is something

of a disappointment; it sounds like an electronic instrument.

How much this is a reflection of the instrument and how much

it’s to do with the age of the recording I’m unsure. In fairness,

I suspect it’s more the latter and when, just for interest,

I compared this recording with a live Boston Symphony Orchestra

performance given just a few months earlier (review)

I found there wasn’t much to choose between the two. When the

organ joins in the Big Tune (1:09) it makes a more positive

impression. The finale as a whole is hugely enjoyable – the

old maestro conducts with vigour and flair – and I enjoyed it

very much even if the recording does get a bit overloaded at

the end.

As I’ve hinted, the recordings do have their limitations. Tubby-sounding

timpani are a frequent feature and the strings sound a bit glassy

at times in the Berlioz overture. The d’Indy suffers from some

distortion, as previously mentioned. Overall, however, the recordings

have come up remarkably well given that they’re nearly sixty

years old. Forget any sonic limitations: what really matters

here is that we have four fine and very enjoyable Beecham recordings,

including two significant additions to his discography. Beecham

admirers, what are you waiting for?

John Quinn

|

|