|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Downloads

from The Classical Shop

|

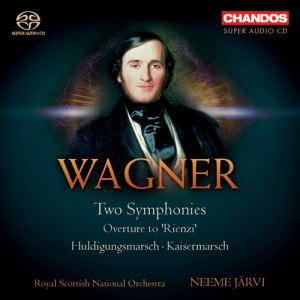

Richard WAGNER (1813-1883)

Symphony in C major, WWW29 (1832) [34.05]

Symphony in E major (orch. Möttl), WWW35 (1834) [19.10]

Huldigungsmarsch,WWW97 (1864) [5.16]

Kaisermarsch,WWW49 (1871)* [8.51]

Rienzi: Overture, WWW104 (1842) [11.16]

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/Neeme Järvi

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/Neeme Järvi

rec. Royal Concert Hall, Glasgow, 19 August 2010* and 21-22 March 2011

CHANDOS CHSA5097

CHANDOS CHSA5097  [79.14] [79.14]

|

|

|

Wagner’s little known efforts at symphonic writing have

received only a handful of recordings, and this was my first

hearing of these works. I came to the recording with foggy recollections

of Romantic Music History lectures characterizing these works

as immature juvenilia, displaying scant evidence of Wagner’s

later compositional genius. After my first listening, I quickly

came to appreciate that such characterization was unfair, and,

perhaps more importantly, incorrect.

The Symphony in C Major, written in 1832, is clearly

modelled on the symphonies of his beloved Beethoven. The first

movement opens with explosive chords, followed by woodwinds

and brass calling to one another over tremolo strings. This

introductory material soon leads into a vivacious Allegro, its

fanfare-like theme brashly proclaimed by brass and strings.

Wagner’s writing exhibits a fondness for constantly shifting

orchestral timbre, sudden dynamic contrast, and intriguingly

differentiated textures. The following Andante features

some lovely melodies, richly harmonized, while the Scherzo

is surely the most playful music Wagner ever penned. The finale

brings the expected counterweight to the first movement, explosive

right from the start. Energetic syncopated writing and a lilting

joyfulness bring Mendelssohn to mind; how Wagner would hate

that.

The liner-notes are informative and interesting, but overly

apologetic about the music’s derivative nature. As author

Emanuel Overbecke notes, “the atmosphere is entirely Beethovenian”.

The same can be said of several composers: Franz Schubert and

Ferdinand Ries immediately spring to mind. Writing after Beethoven’s

death each struggled to find his own individual voice. Surely

that does not negate the value or interest of their compositions?

At this point Wagner was intent on becoming the next great writer

of symphonies, not operas. It is a foolhardy exercise

to judge the worthiness of Wagner’s symphonic music based

on how much it reveals aspects of the mature compositional voice

we know from the operas. Rather, the question should be whether

the symphony is enjoyable and interesting enough for repeated

listening. Will repeated listening offer up new things to discover

and appreciate? Does it express some spiritual and emotional

truth to which we can connect? To all these questions, I answer

a resounding “Yes”.

The Symphony in E Major proved less enjoyable, perhaps because

its manuscript was left largely incomplete. As Overbecke explains,

it was considered lost, but was “then rediscovered, and

acquired in 1886 by Cosima Wagner who asked Felix Mottl to orchestrate

the music.” The manuscript - which was auctioned in 1913

and whose whereabouts today are unknown - consisted only of

sketches for the first movement and 30 bars of an Adagio. It

is pleasant music, but does not exhibit the same imaginative

fire found in the C Major Symphony.

Huldigungsmarsch and Kaisermarsch are festive

occasional pieces, with plenty of nationalist tub-thumping and

martial brass writing. Interestingly, Huldigungsmarsch,

which consists of four progressively faster sections, exists

in two versions. The first, completed by Wagner, is for military

band; the second version, performed here, is for full orchestra.

Wagner began its orchestration, but then, on the advice of conductor

Hans von Bülow, asked composer Joachim Raff to complete

it. Its writing bears more than a passing family resemblance

to Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

The most notable feature of Kaisermarsch is its use of

Martin Luther’s Ein feste Burg. It was originally

to be orchestral only, but Wagner decided to add a sacred text,

to be sung by everyone in attendance, and chose Luther’s

famous hymn for the tune. The integration of the tune into the

music is masterly, and I only wish, though it was surely cost

prohibitive, that the performance could have included singers.

Nevertheless, the performances of both marches leave little

to be desired, played, as here, with obvious relish and genuine

enthusiasm.

Somewhat daringly, this CD of little known works also includes

a performance of the Rienzi Overture, of which there

are 18 recordings currently listed at archivmusic.com. Luckily

this is an excellent performance which I found entirely convincing.

Its solemn beginning moves at a livelier tempo than is the norm

these days. The Allegro episode features resplendent orchestral

playing, especially from the brass.

The recording is up to Chandos’ usual high standards.

The orchestral sound is caught in a large acoustic, adding warmth

without any loss of clarity. The normal stereo sound layer is

splendid, but the SACD brings an extra opulent richness that

serves this music well. Greeted with enthusiasm.

David A. McConnell

See also review by Paul

Corfield Godfrey

|

|