|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads |

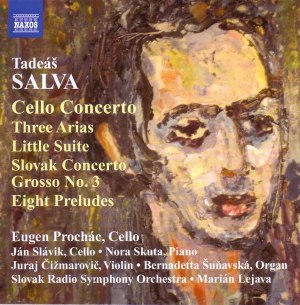

Tadeás SALVA

(1937-1995)

Concerto for Cello and Chamber Orchestra (1967) [11:57]

Three Arias for Cello and Piano (1990) [13:40]

Little Suite for Cello and Piano (1989) [9:03]

Slovak Concerto Grosso No. 3, for Violin, Cello and Organ (1987)

[20:30]

Eight Preludes for Two Cellos (1995) [17:20]

Eugen Prochác (cello)

Eugen Prochác (cello)

Nora Skuta (piano), Bernadette Šuňavská (organ),

Juraj Čižmarovič (violin), Ján Slávík

(cello); members of the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra/Marián

Lejeva

rec. 26 April 2004, 11 May 2004, 17 May 2004, 28 May 2005, 9-10

February 2006, Concert Hall of Slovak Radio, Bratislava, Slovak

Republic

NAXOS 8.572509 [72:53]

NAXOS 8.572509 [72:53]

|

|

|

This fascinating disc presents Tadeás Salva as “one

of the foremost Slovakian composers of his generation”.

I think many collectors would be hard put to name many more.

The booklet note by Vladimir Godár is invaluable, but

given the difficulty of finding information about the composer,

it is a pity that it doesn’t go further. The recordings,

which are very fine, are not new but seem not to have been widely

available before.

The Cello Concerto is very much a work of its time. It might

have been written by any one of several European avant-garde

composers whose reputation has its origin in the sixties. One

of these is undoubtedly Ligeti, and indeed that composer’s

Cello Concerto is cited in the booklet as a model for this one.

The music is hyperactive and immediately striking. I have listened

to it four times and am still only beginning to discern its

form and its aims. The booklet notes tell me that there are

two movements, for example, but I’m still unsure where

the second movement begins. The instrumental ensemble is made

up of five fairly unrelated instruments plus an extensive percussion

section, and the first impression is one of unrelieved scratching,

blowing and - especially - bashing. This kneejerk reaction is

modified on subsequent hearings, during which one begins to

hear a much wider range of instrumental colour and thematic

content. The cello writing is highly challenging, and rarely

exploits the instrument’s singing capacities. There are

aleatoric elements in the work, but I have not seen a score

and would certainly not be able to identify where they occur.

The work is a compelling one, but it does not give up its secrets

easily. The performance seems sensationally surefooted and committed.

One’s first reaction is that this is to be a challenging

disc. This turns out to be only partly the case, as later in

the composer’s career he turned more and more to folk

music, integrating it into his own, modernist style. Twenty

years later, for example, in the Slovak Concerto Grosso No.

3 - Salva adopted this title for several of his chamber works

- the music is far more tonal and with perfectly audible folk

influence. It is still packed with incident, with only a few

points of repose occurring in the last of the three movements.

The instrumental writing is highly inventive, and this is a

most attractive and enjoyable work overall.

If the Cello Concerto barely makes use of the instrument’s

singing power, the Little Suite makes up for it. That feature,

combined with a musical language even more tonal and consonant

than that of the Concerto Grosso, combine to make this work

more approachable still. In addition should be noted the real

distinction and attractiveness of the musical ideas. The Three

Arias are less immediately attractive but repay no less repeated

listening. In the first piece cello and piano parts turn obsessively

around a very few short motifs. This, like much of the music

in this collection, is nervous and constantly moving. The second

aria begins in much the same mood, and indeed the whole work,

with the exception of one short passage in the third piece where

the temperature dips for an instant, is one of unrelenting intensity.

The Eight Preludes were left unfinished at Salva’s untimely

death. Each of the short pieces makes much use of imitation

and folk elements. The music is rather ascetic, an almost inevitable

consequence of the forces used. Perhaps more were planned, but

otherwise there is nothing here to suggest that the work is

incomplete, not even the abrupt, unexpected endings which are

a feature of many of the works in this collection.

The name Tadeás Salva was new to me, and may well be

to the majority of readers. This is a useful introduction to

his work. Eugen Prochác is a very fine cellist indeed,

and I should be very fascinated to hear him in more central

repertoire. He is joined on this disc by a number of other Slovak

instrumentalists. With world-class playing such as this, they

are indeed splendid ambassadors for the composer.

Anyone with an interest in the byways of modern music should

not miss this disc.

William Hedley

|

|