|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound Samples & Downloads

|

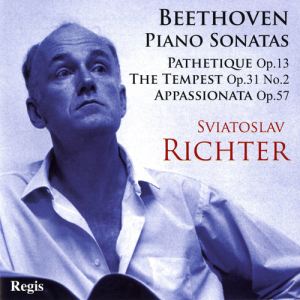

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Piano Sonatas: No.8 in C minor, Op.13

Pathétique* [17:33]; No.17 in D minor, Op.31 No.2 The

Tempest [23:33]; No.23 in F minor, Op.57 Appassionata [23:44]

Sviatoslav Richter (piano)

Sviatoslav Richter (piano)

rec. (Op.13: 4 June 1959, Moscow? Op.31 No.2: 1-5 August 1961,

London? Op.57: 29-30 November, 1960, Carnegie Hall, New York City, USA?)

mono*/stereo

Recordings first published in 1961

REGIS RRC1384 [65:08]

REGIS RRC1384 [65:08]

|

|

|

The Richter discography is confusing, complicated by the artist’s

progressive dislike of studio recording and our consequent reliance

upon recordings of live performances. Regis did us a great favour

in issuing his glorious account of the Beethoven Sonatas nos.

3, 4 and 27, recorded in the 1970s and licensed from Olympia.

At first I found it hard to summon up the same gratitude for

the clangourous, mono sound of the Pathétique

that opens this collection. The high levels of distortion and

muddy ambience severely restrict the pleasure to be derived

from this magisterial performance. They also serve to exaggerate

the restless drive of Richter’s interpretative stance,

untempered by any depth or beauty of sound. As such, it makes

harsh listening.

Things look up with the second two items, recorded in very listenable

stereo. The only recording information we are given by Regis

is that they were “first published in 1961”. The

“Gramophone” quotation identifies the Appassionata

as being the “Living Stereo” recording made for

RCA Victor. It was used as the ‘filler’ for his

Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 made with Leinsdorf, itself a superb

performance. The Tempest could well be the recording

made for EMI and issued along with the Schumann Fantasia.

The Pathétique is presumably the 1959 studio recording

for Melodiya. Richter aficionados will no doubt identify their

specific origins.

Although nos. 17 and 23 here are satisfactory, some might feel

the need to try to locate a recording of Richter playing the

Pathétique in better sound, given that this Regis

version is trying. However, the Richter discography contains

only two mono recordings, one a 1959 studio event on Melodiya

and the other a live 1958 one on Parnassus. This one on Regis

is presumably that same 1959 studio recording, currently available

in the Melodiya Richter Edition. The Appassionata and

The Tempest are also available recorded live in 1965,

on the Praga and Music and Arts labels.

Discographical and sonic matters apart, what of the quality

of these performances? Richter was in the plenitude of his powers

when these performances were recorded, just at the time he was

being introduced to the Western world.

Despite the rough, cavernous sound in the Pathétique,

the combination of muscular dynamism and headlong propulsion

alternating with gentle lyricism is still very much in evidence

and alerts us to the fact that we could be listening to no other

pianist.

It is nonetheless a relief to turn to the Tempest in

good stereo. Richter draws out the opening Largo daringly,

using his glorious singing tone to span the gaps and create

the effect of legato. He engineers the maximum contrast between

the slow episodes and the Allegro passages. Beethoven and Richter

were made for each other. The close recording allows us to hear

the opening notes resonate for what seems like forever as Richter

conjures up vast spaces. The Mozartian Adagio has a delicate

poise and limpid beauty without sentimentality. The lilt of

the Allegretto is seductive, then the music morphs into

something more violent and disturbing. Richter narrates a story

employing many voices.

The Appassionata was one of Richter’s signature

works, frequently performed and recorded. Here, it really lives

up to the implications of its sobriquet. To me it seems perverse

to require restraint and understatement in this, one of the

most energised and tumultuous compositions ever written for

the piano. This is a bold, brilliant account which manages to

justify what could sound like extremes of fast and slow in less

skilful hands. You will never hear greater dexterity or more

thrilling playing than the way he steers the Presto to

its climactic conclusion. This recording remains justly famous

for its power and poetry.

Ralph Moore

|

|