|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

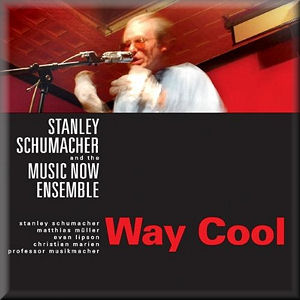

Way Cool

Audio Logo [0:09]

Cognitive Dissonance [4:53]

Linguistic Engineering [2:44]

High Art? [2:40]

Darkness Of Error [5:41]

Trombone On The Edge [5:21]

Out Is In [4:38]

Way Cool [6:10]

Back Talk [5:24]

Ambient Event [2:52]

Hearing Disorder [5:14]

Where’s The Melody? [3:36]

Stanley Schumacher and the Music Now Ensemble

Stanley Schumacher and the Music Now Ensemble

Stanley Schumacher (trombone, voice), Matthias Mueller (trombone), Evan Lipson (string bass), Christian Marien (percussion), Professor Musikmacher (oral arts)

rec. Westwires Recording, Allentown, PA, USA, dates not given

MUSICKMACHER PRODUCTIONS MM005 [50:08]

MUSICKMACHER PRODUCTIONS MM005 [50:08]

|

|

|

This is one of those improviser ensemble releases which could

as easily end up in the Jazz review pages as the contemporary

‘classical’ side of the coin, although the information sheet

which accompanied my review copy clearly states that this is

“Improvised Contemporary Art Music (Classical).” The jazz association

comes to a degree from the instrumentation, and anything with

a title like Way Cool has to accept that their disc may

be redirected by inexpert record shop rookies. Stanley Schumacher

has also worked with jazz-oriented musicians such as Lukas

Ligeti in the past, but the main point to classical music

consumers is that this is as much A. Braxton as it is L. Berio.

Looking at the duration of the pieces tamed my initial resistance

to this CD, as did Schumacher’s intelligent sense of humour,

which is cleverly worked into the music, delivering quite sophisticated

self-referential messages. Cognitive Dissonance is an

intense exploration of the sonorities and interaction of the

instruments present, as well as giving us a taste of Prof. Musikmacher’s

parlando vocalisations or ‘oral arts’ as they are called

here. These sounds are delivered straight or through the tubes

of a trombone, mixing the perspectives and semantics of vocal

sounds which are suggestive of emotion and mood, and their equally

expressive instrumental counterparts. Referring to Berio again,

some of the use of vocals here may remind listeners of Cathy

Berberian’s remarkable flexibility as a vocal artist as well

as a straight singer. Growling is exchanged for lighter noises

in the trombone/voice duet which is Linguistic Engineering,

which includes the first time I’ve heard snoring used as a musical

device.

High Art? is a crucial track, in which the essence of

our experience of this kind of music is confronted by the creator

himself. “Where’s the melody?” “This is weird”, “I can’t

listen to this”, and a whole shopping list of expected

responses are integrated into the track, winning me over at

a single stroke. Yes, it can be ‘difficult’ if your references

are limited to more conventional traditions, but this takes

the kind of theoretical thoughts posed by John Cage and folds

them back onto both us and the musicians. Why are they playing

like this? “Do they know what they’re doing?” Well, yes

they do – it may not be instantly appealing, but it does open

doors into areas of expression not covered by 4/4 in G major.

As I write, my place of work the Royal Conservatoire in The

Hague is involved in a major international ‘improvisatieweek’

which comes with a health warning: “Improvisation may seriously

improve your performance.” This is a form of music which is

taken very seriously by a wide spectrum of musicians, but I

for one am glad to hear Schumacher able to acknowledge with

admirable lightness of touch that it can have an aversive effect

on many audiences.

Bear with me on this as a general point, but my only doubt about

this music is, for want of a better word, its legitimacy in

the recorded medium. This works in two extremes. As with many

of John Cage’s scores, the improvisational element means that

no two performances will ever be the same, so in a sense only

the ‘live’ performance is the genuine experience – the music

formed before us, shaped by the composer and the musicians,

but creating something genuinely unique and hopefully rather

special. Play back the recording and it becomes repetition.

The other extreme is that these pieces therefore can exist only

in the recorded medium, but the question arises: do we want

to hear them more than once?

In the case of Way Cool there are enough interesting

musical events to make this more than just a souvenir of a well

prepared recording session, and let’s be honest, how other than

on a recording are we going to deliver this or any other music

to an audience wider than a concert venue. I’ve been involved

with improviser ensembles myself in the past, and know how highly

sensitive the end result depends on a deeply felt synergy between

all of the players, and how easily the whole thing can be ruined

by a single musician who is on a different wavelength to the

rest. The Music Now Ensemble is clearly a bunch of musicians

who have a natural feel for each other’s musical and dramatic

strengths, and this album can serve as an object lesson to performers

keen to explore non-notated musical communication. There is

much to be said for the relative compactness and intelligent

shaping of the musical statements made here, and I for one am

grateful that the music making is less about ego and more about

listening and expanding the limitations of the instruments and

their interactions.

The title track is an excellent little moral story about a “snotty

nosed, iPhone-iPod-MP3-playing punk”, proving that irony does

exist in the US. There is plenty of contrast between numbers,

from the high-octane blast of energy which is Back Talk,

to the moody atmosphere of Darkness Of Error and landscape

of Ambient Event. Elements of continuity include a ritualistic

triangle whose sharp ‘ting’ serves as a kind of dinner gong;

stopping or starting certain musical events. I won’t promise

that this is an album you will definitely like, but if the intricacies

and freedoms of improvisation are aspects of music you feel

willing to explore then this is as good a place to start as

I could name. Don’t expect to hear any tunes however: indeed,

like Wally or Waldo, where is the melody?

Dominy Clements

|

|