|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS |

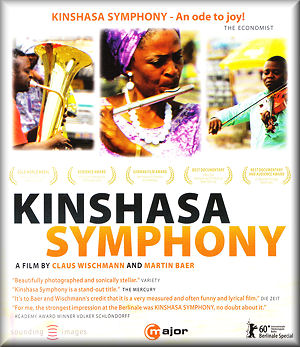

Kinshasa Symphony

A film by Claus Wischmann and Martin Baer

A film by Claus Wischmann and Martin Baer

Picture: 1080p/16:9/NTSC

Sound: PCM stereo, dts-HD-MA 5.1

Regions: A/B/C

Subtitles: English, German, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Korean,

Russian

C MAJOR 709004

C MAJOR 709004  [95:00 film; 10:00 bonus]

[95:00 film; 10:00 bonus]

|

|

|

Kinshasa, the Congolese capital, is a sprawling city of ten

million. It lies at the heart of a country blighted by civil

strife, the latest of which - the so-called Second Congo War

that began in 1998 - has killed more than five million people.

And despite a fragile peace, the violence continues in the east

of the country. Against this backdrop, the very existence of

the Orchestre Symphonique Kimbanguiste (OSK) is nothing short

of a miracle. Composed of largely self-taught musicians and

singers it’s an extraordinary band of human beings who

travel miles to get to rehearsals, buy their own sheet music

and - when necessary - make their own instruments.

And that’s just for starters. Even more astonishing is

the enthusiasm and good humour that infuses this project. There

are problems aplenty, not least an intermittent supply of electricity,

but then one of the orchestra’s viola players, Joseph

Lutete, is also a skilled electrician and will down his instrument

to fix the generator. As for the orchestra manager Albert Matubanza,

whose supply of instruments was long since looted, he’s

reduced to touring scrap yards for off-cuts to make a double

bass. And from the outset the snippets of O fortuna, Va pensiero

and the rehearsals for the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth

are all played and sung in a way that’s uniquely African.

There’s even an improvised Boléro-in-the-bush

that had me laughing out loud at the ingenuity and persistence

of these musicians.

Film-makers Claus Wischmann and Martin Baer have opted for a

very simple, self-revealing narrative style, in which the orchestra

members introduce themselves to camera in the most natural and

disarming way. Flautist Nathalie Bahati speaks candidly of her

unexpected pregnancy, absent boyfriend and unscrupulous landlord,

all part of a daunting daily grind that’s borne with remarkable

fortitude and grace. And then there’s the OSK’s

founder, Armand Diangienda, a former pilot who lost his job

and formed the orchestra in 1994. He and the ongoing rehearsals

for that Beethoven finale - the words of which are especially

poignant in this context - form the central thread of this fascinating

drama.

Professional musicians are well-known for their gripes and grumbles,

and I daresay they wouldn’t be too keen to rehearse in

the cramped, run-down spaces their African counterparts have

to endure. And if we have to work hard to persuade others of

the pleasures of classical music spare a thought for the young

man sent out into the city’s decaying suburbs - built

for rich Belgians - to deliver leaflets for the upcoming concert.

The local ‘pop’ that peppers the soundtrack and

the incomprehension of the populace is countered by good humour

and high spirits all round. This is intercut with shots of everyday

life in the city and Diangienda cajoling his motley choir in

the Ode to joy. The music is always recognisable, but

rhythms are distinctly African, blessed with an age-old fluidity

and cadence that’s very moving indeed.

And as anyone familiar with Africa will know, public transport

is a fraught affair. Like everyone else Lutete and his fellow

musicians have to squeeze on to a packed van or mini-bus to

get to rehearsals. It’s frustrating, but it’s endured

with none of the exasperation and hostility one might expect.

This is a daily rhythm of its own, and everyone seems willing

enough to sway with it. Even when Lutete practises amidst the

crowds - one of several rather wistful vignettes in the film

- his viola takes on a timbre all of its own, both songful and

searching; and that pretty much sums up the sound of this orchestra

as a whole, whose tuning-up at a rehearsal may be wayward but

it still has that frisson we all know so well.

This is a well-crafted film, and there’s a palpable tension

as all the strands are pulled together for the final concert.

And speaking of strands, fiddlers will be aghast to hear that

replacement strings are sometimes made from bicycle brake cables.

Oh, you need a trumpet bell? Try this wheel rim from a mini-bus.

This really is a scratch orchestra, and there’s

a delightful sequence in which two singers struggle with Schiller’s

texts, coming up with the strangest pronunciations. As always,

there’s a passion, a fierce hunger, that conquers all.

And it’s easy to understand the sentiments of one of the

singers, for whom the music is a passport - albeit temporary

- to somewhere ‘far away’.

But escaping the problems of daily life isn’t always that

easy. Cello player Joséphine Nsemba - who makes and sells

omelettes from a market stall - has to struggle with the price

of eggs and, as a parent, wrestle with fears for her young son

as he’s operated on in a terribly basic hospital. Even

the doughty Diangienda comes close to despondency when rehearsing

the choir, which is in deep disarray. This is the rough, unforgiving

milieu in which these people find themselves, and for

a few seconds the mask slips and desperation shows.

That said, the big night arrives - it takes place outside, under

floodlights - with the Ode to joy and O fortuna.

And how does it go? Well, I suggest you buy this disc and find

out. The bonus track has four short items - Joséphine

and Albert make music, Joseph at the market, Héritier

teaches, and Chantal on her daily bread run. They afford a glimpse

of private moments, all captured in a relaxed, non-intrusive

way. As for the editing, it’s wonderfully poetic at times

- a smile, a frown, a look of quiet contentment - the final

frames especially so.

Any grumbles? Not really, although the narrative does falter

a little towards the end. That said, the leisurely, unforced

pace of this documentary is a pleasure from start to finish.

And yes, many issues are left untouched but, to be fair, this

isn’t a multi-part television series with plenty of time

to tease and probe. As for Martin Baer’s cinematography,

it’s always crisp and elegant, colours vibrant and images

sharp; most welcome, though, is the refreshing lack of voice-overs

or overt editorialising, so the film never becomes a political

statement or polemic.

An inspiring story, movingly told.

Dan Morgan

http://twitter.com/mahlerei

|

|