|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads |

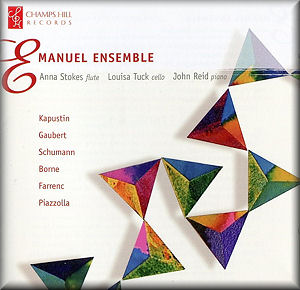

Nikolai KAPUSTIN (1937-)

Trio, Op 86 [19:12]

Philippe GAUBERT (1879-1941)

Pièce romantique [7:41]

Robert SCHUMANN (1810-1856)

Adagio and Allegro in A flat, Op 70 [9:02]

François BORNE (1840-1920)

Fantaisie Brillante sur Carmen [11:13]

Louise FARRENC (1804-1875)

Trio Op 45 [24:59]

Astor PIAZZOLLA (1921-1992)

La Muerte del Ángel [3:32]

Emanuel Ensemble (Anna Stokes (flute); Louisa Tuck (cello); John

Reid (piano))

Emanuel Ensemble (Anna Stokes (flute); Louisa Tuck (cello); John

Reid (piano))

rec. 17-18 August 2010, and 22 May 2011 (Borne), Music Room, Champs

Hill, West Sussex, UK

CHAMPS HILL RECORDS CHRCD023 [75:37]

CHAMPS HILL RECORDS CHRCD023 [75:37]

|

|

|

You’ve probably never heard much of this music, and you’ll

probably enjoy all of it. The Emanuel Ensemble, a young trio

comprising a flute, cello, and piano, have really put together

a smart, adventurous, and totally pleasing program here, ranging

from contemporaries Robert Schumann and Louise Farrenc to the

1990s jazz world of Nikolai Kapustin. In between we’ve got a

Carmen fantasy, a serenade by the legendary flautist

Philippe Gaubert, and a Piazzolla tango. What’s not to like?

Kapustin’s Trio begins the program. Nikolai Kapustin

got his start in the early 1960s, as, in a way, the great hope

of Soviet jazz: YouTube preserves fragments of his appearances

on state television, including a jaw-dropping ‘Toccata’ for

solo pianist and big band, which the composer dispatches with

an ease and dispassion which make James Bond look neurotic.

All of Kapustin’s music is totally jazzy to the ear, and most

of it sounds improvised (his greatest influence is Oscar Peterson),

but all of it is very carefully notated and written out, indeed

as instruction-laden as a Mahler score. This paradox has been

confusing critics ever since it started, but the composer, still

alive, pays them no heed. His Trio, from 1998, is one

of the composer’s first major chamber works, though he wrote

it in his mid-fifties. The outer movements are jaunty and virtuosic

showcases for his style of apparent improvisation but genuine

development of central themes. The slow movement is, by contrast,

much more sensitive than you’d expect. This is all wholly enjoyable,

fairly compactly developed, and with very distinctive personalities

assigned to each instrument. If you like the idiom, you’ll also

love Kapustin’s brilliant string quartet.

We travel back in time for much of the rest of the program.

Philippe Gaubert was a noted composer of quite a lot of flute

music, as well as several well-executed ballets. The Pièce

Romantique shows an equal sensitivity toward the cello,

which ushers in the beautiful main tune; the seven-minute work

really lives up to billing as a lyrical romance of great craft.

The center of the program shrinks the trio down to two players:

Robert Schumann’s Adagio and Allegro, originally for

horn and piano, here showcases cellist Louisa Tuck, while François

Borne’s Carmen Fantasy does for the flute roughly what

Sarasate’s Carmen piece did for the violin. In the Carmen

fantasy there’s an engaging obsession with the opera’s dark

“fate” motif, which brings out the flute’s lower, more expressive

side. It’s a welcome change from the instrument’s stereotypically

chipper persona.

The booklet rightly calls Louise Farrenc the best female composer

of the 19th century, and I would venture to add that

she was one of the best composers of any sex between the death

of Beethoven and the rise of Brahms and Wagner. Her three symphonies

(not two, as the essay misstates) are enormously impressive,

and they’re also the Farrenc you’re most likely to know, since

CPO recorded the full cycle. CPO also has a disc

of her other piano trios (piano, violin, cello; piano, clarinet,

cello) and a woodwind sextet.

The trio offered here begins with a melancholy main tune of

Mendelssohnian build; the piano writing is a solid backbone

to the music, and the tight construction of the opening allegro,

with its really exceptional melodies and unerring dramatic pace,

would have been a proud moment for Schumann or the young Brahms.

It’s also another good place to admire the affinity the Emanuel

Ensemble players have for each other; I thought, as I listened,

that this had better be the first of many CDs from the group.

Farrenc’s trio is in four movements, and the last three are

almost exactly five minutes each, highlighted by a presto finale

which poses great dangers to the flautist and very skillfully

brings the music from E minor to E major with wit and ingenious

style. I’m again reminded of how difficult it is to explain

Farrenc’s neglect.

Everything is brought together by a Piazzolla encore, La

Muerte del Ángel, vividly arranged (by whom?) to give each

instrument a fiercely sexy moment in the spotlight. The booklet

is a bit of a letdown, as there are no track timings of any

kind and the biography of Farrenc is, as I’ve noted, not totally

accurate. But this is such an exceptionally fine young ensemble,

and such a marvel of a program, that I can’t possibly hold back

from the highest recommendation. The sound quality, up close

and personal but with plenty of warmth, is icing on a very fine

cake.

Brian Reinhart

|

|