|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads |

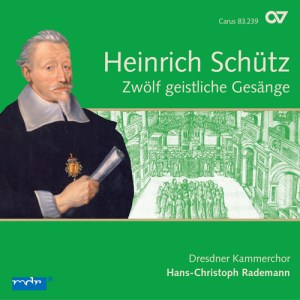

Heinrich SCHÜTZ

(1585-1672)

Geistliche Gesänge (1657) SWV 420-431

Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit SWV 420 [4:56]

All Ehr und Lob soll Gott sein SWV 421 [5:38]

Ich glaube an einen einigen Gott SWV 422 [5:25]

Unser Herr Jesus Christus SWV 423 [4:57]

Ich danke dem Herrn von ganzem Herzen SWV 424 [4:18]

Danksagen wir alle Gott, unserm Herren Christo SWV 425 [1:26]

Meine Seele erhebt den Herren SWV 426 [6:45]

O süßer Jesu Christ, wer an dich recht gedenket SWV 427

[3:52]

Die deutsche Litanei SWV 428 [10:19]

Aller Augen warten auf dich, Herre SWV 429 [3:47]

Danket dem Herren SWV 430 [4:33]

Christe fac ut sapiam SWV 431[4:05]

Dresdner Kammerchor/Hans-Christoph Rademann

Dresdner Kammerchor/Hans-Christoph Rademann

rec. October 2009, MDR Leipzig, kleiner Sendesaal

Texts and translations included

CARUS 83.239 [60:01]

CARUS 83.239 [60:01]

|

|

|

'Sketched in his spare time' according to one account, the Twelve

Sacred Songs of Heinrich Schütz were collected by Christoph

Kittel for publication in 1657 'to the honour of God and for

practical Christian use in churches and schools'. Thus

the first six correspond to the order of the Mass (Kyrie to

Benediction), numbers 7 and 8 to the Vespers, No. 9 was designed

for use in the litany in major services, whilst the last three

were originally conceived on a domestic scale - they're still

sung as graces in the boarding school of the Kreuzchor in Dresden.

Which, as the notes suggest, would doubtless have pleased Schütz.

So this is Schütz on a more reserved and deliberately limited

scale than his more extrovert and public works, those fertile

products of his questing musical mind that generated such masterpieces

as the German Magnificat, and so many others. The music in the

Sacred Songs is measured, considered and restrained. Kyrie,

Gott Vater in Ewigkeit, for example, evinces the kind

of measured gravity, in amplitude, tempo and mood that recurs

throughout the set. The noble seriousness of All Ehr und

Lob soll Gott sein and the control of metre and flow in

Unser Herr Jesus Christus points to the narrow expressive

limits of the music. But to say that is not to suggest that

it is without intensity or moving directness. On the contrary,

whilst it may deliberately avoid those feats of anthiphonal

splendour that largely added lustre to his name, these more

specifically rooted pieces shine the more brightly for their

self-effacement and self-control. Even so very brief a

setting as Danksagen wir alle Gott, unserm Herren Christo

- which is barely a minute and a half in length - reveals

in its repeated phrases a brisk and affirmative piety that could

only be the work of a master. Similarly, the simple and unadorned

Danket dem Herren generates a greater sense of direction

largely through its avoidance of extraneous detail; nothing

is allowed to impede the textual message, and all technical

flourish and bravura is put to one side.

This fourth volume in the complete Schütz series on Carus

may not, therefore, seem an obvious reference point, given its

unSchütz-like reserve. When the performances are as fine

as these, and when the recording has been so well judged, then

there can be no reservations.

Jonathan Woolf

|

|