|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS |

Hugo WOLF (1860-1903)

Six songs from the Italienisches Liederbuch:

Gesegnet sei, durch den die Welt enstund (1890) [1:22]

Schon streckt’ ich aus im Bett (1896) [1:42]

Geselle, wolln wir uns in Kutten hüllen (1891) [2:12]

Und willst du deinen Liebsten sterben sehen (1891) [2:03]

Sterb’ ich, so hüllt in Blumen meine Glieder (1896) [2:21]

Ein Ständchen Euch zu bringen kam ich her (1891) [1:42]

Erich Wolfgang KORNGOLD (1897-1957)

Vier Lieder des Abschieds, Op. 14 (1920-21) [14:52]

Gustav MAHLER (1860-1911)

Um schlimme Kinder artig zu machen (1887-91) [1:56]

Erinnerung (1889) [2:24]

Ich ging mit Lust (1887-91) [4:19]

Aus! Aus! (1887-91) [2:29]

Robert SCHUMANN (1810-1856)

Kerner Lieder, Op. 35 (1840) [32:14]

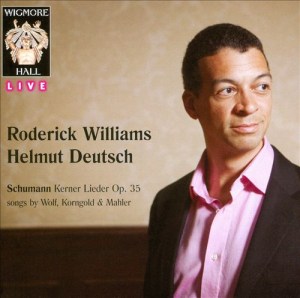

Roderick Williams (baritone); Helmut Deutsch (piano)

Roderick Williams (baritone); Helmut Deutsch (piano)

rec. live, 25 February 2011, Wigmore Hall, London. DDD

German texts and English translations included

WIGMORE HALL LIVE WHLIVE0055 [70:32]

WIGMORE HALL LIVE WHLIVE0055 [70:32]

|

|

|

At the moment there are a large number of really fine

exponents of art songs before the public and Roderick Williams

is up there with the best of them. He’s attracted particular

acclaim for his work in the field of English song but he’s

equally at home in mélodies and lieder

and this very fine recital amply confirms his expertise in the

latter category. Williams has made a discerning choice of repertoire

here and each group offers contrast within it and plays to his

strengths. Apart from the sheer pleasure of the sound of his

voice something that I particularly admire about Roderick Williams

is his care over the texts. His diction is invariably very clear

but more than that you can tell that he’s taken considerable

trouble to study the poetry and to understand it so that he

puts it across to his audience with exceptional intelligence.

He also characterises the texts very well indeed. All this is

very much in evidence during this programme.

So, in the Wolf group he brings to life the various characters

depicted in Geselle, wolln wir uns in Kutten hüllen

in a keenly observed and entertaining portrayal. By contrast,

in the very next song, Und willst du deinen Liebsten sterben

sehen, he caresses the words, delivering them with wonderfully

warm, smooth tone. Both Williams and Helmut Deutsch display

exemplary control in Sterb’ ich, so hüllt in Blumen

meine Glieder and the soft high notes that the singer produces

on the very last word, “deinetwegen” betoken an

enviable technique, effortlessly deployed. Indeed, throughout

this recital Roderick Williams’s use of his top register

is quite superb.

The Korngold songs are an enterprising choice. The composer’s

rich late Romantic palette can sometimes seem a little cloying

but not here. The description of the music in the notes as “framed

by a bittersweet halo” seems very apt. The first song,

‘Sterbelied’, which sets a German translation of

a poem by Christina Rossetti, is a wistfully melancholic remembrance

of the past. Roderick Williams’s enviable legato, the

high notes produced purely and evenly, enables him to do full

justice to the song. The demanding, often high-lying vocal line

of the third song, ‘Mond, so gehst du wieder auf’,

is a real test of technique but Williams seems effortless in

projecting the line in an expressive reading of this regretful

song.

The Mahler group is well chosen with two outgoing songs encasing

a pair of more thoughtful ones. I very much enjoyed Ich ging

mit Lust, a setting of sophisticated innocence. This is

another opportunity for Williams to demonstrate his flawless

top register and both musicians invest this song with pleasing

delicacy. Um schlimme Kinder artig zu machen is almost

archaic in style - deliberately so - but it offers Williams

another opportunity to display his gift for characterising words

and thereby for telling a story: he takes the opportunity with

relish. Aus! Aus! is one of Mahler’s military-inspired

songs. Williams brings it vividly to life, much to the delight

of the audience.

Schumann’s settings of twelve poems by Justinius Kerner

(1786-1862) are some of the fruits of his miraculous Liederjahr,

1840. However, as Gavin Plumley points out in his notes, despite

the joy of marriage - at last - to Clara, by no means all the

songs that Schumann wrote in that prolific period reflect that

joy and the Kerner collection moves from positive beginnings

to a much bleaker conclusion. Plumley says that during the performance

preserved here “Roderick Williams’s jovial presence

grew increasingly sad.”

The whole set is splendidly done but highlights for me included

the sixth song, ‘Auf das Trinkglas eines verstorbenen

Freundes’. This song depicts the veering moods of a man

taking refuge in the bottle and Williams encompasses all the

different aspects of the song most convincingly. He’s

tremendously expressive in the aching melancholy of ‘Stille

Tränen’; yet for all the expressiveness he never

sacrifices the line or purity of tone. This is a memorable performance.

The last two songs are movingly done. In ‘Wer machte dich

so krank?’ it’s as if resignation has drained the

poet of emotion. Finally, in ‘Alte Laute’ Williams

offers some exquisite quiet singing in a reading that’s

engrossing and marvellously controlled. After a decent pause

the Wigmore Hall audience is vociferous in its appreciation;

and no wonder.

I’m conscious that I’ve said very little about the

contribution of Helmut Deutsch. In his biography the list of

singers with whom he has worked reads like a veritable Who’s

Who of lieder singers, including such greats as Irmgard

Seefried and Hermann Prey as well as such luminaries as Matthias

Goerne and Jonas Kaufmann from the present generation. With

such a pedigree you could expect him to be a splendid partner

for Roderick Williams and so it proves.

Both the sound quality and documentation are very good. This

is a marvellous, deeply satisfying lieder recital and

we should be thankful that it’s been preserved on disc

for a wide audience to savour.

John Quinn

|

|