|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Download

from The Classical Shop

|

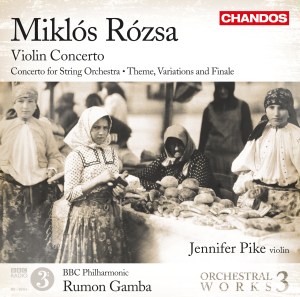

Miklós RÓZSA

(1907-1995)

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 24 (1953) [31:22]

Concerto for String Orchestra, Op. 17 (1943) [23:55]

Theme, Variations and Finale, Op. 13 (1933) [19:27]

Jennifer Pike (violin)

Jennifer Pike (violin)

BBC Philharmonic/Rumon Gamba

rec. MediaCity UK, Salford, 12, 14 December 2011; 7 January 2012

(Violin Concerto) and 12 June 2012 (Concerto for Orchestra, Finale

only)

CHANDOS CHAN10738 [75:08]

CHANDOS CHAN10738 [75:08]

|

|

|

I have to admit that I have not consciously heard any music

by Miklós Rózsa before reviewing this disc - with

one exception. I imagine that I am not the only person to have

known the romantic film score to Spellbound without really

understanding anything about the composer. This present disc

is ‘Volume 3’ of a Chandos retrospective of Rózsa's

concert music, so I have missed a fair chunk of his compositions

- including a tantalising-sounding Overture to a Symphony

Concert (vol.

1) and an apparently aggressive Cello Concerto (vol.

2). However the present disc would seem to be an excellent

place to begin my explorations: it is always possible to back-track

later.

Rumon Gamba has described the background to this cycle of recordings:

- ‘Having made many discs of the film music by composers

whose concert work is well known, for example, Arnold and Vaughan

Williams, I thought it would be interesting to look at a very

well-known film composer and profile his concert works, which

have been overshadowed by his big-screen successes. The orchestral

music of Miklós Rózsa is extremely exciting, passionate

and intoxicating, and deserves to be better known.’ [Presto

Classical Review: accessed 02/11/12]

A few words about the composer may be of interest. He was born

in Budapest and after study at Leipzig University and Conservatory

moved to Paris in 1932. His first two published works were a

String Trio and a Piano Quintet. At the advice of Arthur Honegger,

Rózsa began to explore the possibility of writing film

music. He went to London and worked at fellow Hungarian Alexander

Korda’s London Film studios. In 1939 he went with Korda

to Hollywood to compose the music for The Thief of Baghdad.

Although this film starring Conrad Veidt and John Justin was

a British production, the wartime situation necessitated its

completion in California. He settled in Hollywood and subsequently

wrote the music for dozens of films including Ben Hur,

Quo Vadis and El Cid.

His final motion picture, Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid was

released in 1982. Miklós Rózsa suffered a stroke

the following year and subsequently confined his activities

to concert music. However unlike film-music composers such as

John Barry, Rózsa always managed to balance the ‘day

job’ with his keen interest in writing music for the concert-hall.

He achieved this by having a contract that allowed him time

to write his ‘art’ music during the summer months

at his Italian retreat.

The Violin Concerto is fantastic. The work was completed at

the composer’s Italian hideaway at Rapallo in 1953. It

was subsequently revised in Hollywood the following year. The

Concerto was dedicated to Jascha Heifetz who assisted the composer

in a number of technical details. It was duly premiered to huge

critical acclaim in 1956 by Heifetz and the Dallas Symphony

Orchestra conducted by Walter Hendl. It was recorded shortly

afterwards.

I am reminded of Walton’s great Violin Concerto in much

of this music. I guess that it is the balance between the lyricism

and the ‘bustling energy’ which characterises both

works. There is certainly nothing of the film-score in these

pages. One or two reviewers of previous recordings of this work

have been less than generous in their assessment of this work

- E.G. in The Gramophone April 1989 suggests that it

is not ‘great music’ and T.H. in the same publication

states that [the work] ‘is without any striking ideas’.

He suggests that it cannot be considered alongside the concertos

of Prokofiev, Sibelius and Bartók. I beg to differ. I

find the work, dynamic, haunting and often quite beautiful.

It is easy to advance musical allusions in this score to Kodály,

Bartók and Walton - however, this is a personal, challenging

and technically difficult work that demands to be in the repertoire

on its own account. I cannot compare Jennifer Pike’s playing

to that of Heifetz’s 1957 recording - although it is available

on CD. However, I found her playing impressive and expressive.

It appears to me to be an excellent account of this great work.

The Concerto for String Orchestra, Op.17 is an important work

by any standards. It was composed in New York in 1943 and reflects

the composer’s anxiety over the war-time situation in

his native Hungary. The liner-notes point out that Rózsa

had just completed the film score for Korda’s classic

film based on Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book. He

felt that he needed to write something ‘non-cinematic’.

This present work is a million miles away from the soundscape

of Hollywood. It is brutal, bleak and dramatic and explores

a wide range of emotion across its three well-balanced movements.

The heart of the Concerto is the intense, elegiac slow movement.

It is here, more than in any other part of the work that Rózsa’s

love and concern for Hungary makes itself felt. The work was

dedicated to the composer’s wife, whom he had recently

married.

The earliest of the works presented on this disc dates from

before the start of Rózsa’s film music career.

The Theme, Variations and Finale was completed in Paris

during 1933. The liner-notes outline the background. Apparently

the opening theme was devised as the composer was leaving Budapest

to travel to Paris. He has said his farewells to the family

and was no doubt feeling a little melancholy; this is reflected

in the opening oboe theme. This is followed by eight variations.

I was particularly impressed with the ‘mercurial’

second ‘scherzando’ variation and the heart-breaking

fourth, ‘Moderato con gran espressione’. It is here

that we see film music potential at its clearest. The finale

is deceptive: it begins in a whimsical folksy mood, only to

be ousted by a massive outburst from the orchestra which brings

this important work to a dramatic conclusion. The music was

to give Rózsa an international reputation. It was duly

taken up by Bruno Walter, Eugene Ormandy and Leonard Bernstein.

I was impressed by every aspect of this CD. The music was to

a large extent revelatory. These are works that have a life

of their own - they owe little to the ‘Hollywood style’

that was required of the composer in his main job. This music

is interesting and demanding of the listener but never off-putting.

The playing requires and here receives virtuosity and a dazzling

display of instrumental colouring. The soloist, Jennifer Pike

- who is an exclusive artist to Chandos - plays a stunning concerto.

We will surely hear much more from her. The sound quality of

the recording is superb and reveals all the colour and dynamics

of these complex scores.

The liner-notes by Andrew Knowles are extensive: a model of

their kind. There is so much important information here about

the composer and the music. It has been difficult to synthesise

it all for this review.

The most exciting thing of all is that there is a considerable

catalogue of orchestral and concerted music yet to be explored

in this series. Let us hope that this is not the last volume

in this ‘retrospective’. I would love to hear the

Symphony in 3 Movements, Op. 6, the Piano Concerto, Op. 31 (1967)

(review)

and Kaleidoscope, six short pieces for small Orchestra,

Op. 19a (1946).

Miklós Rózsa’s music could be characterised

as being the fire and passion of Hungarian folk music showcased

in the romantic extravagant style of Hollywood but always reflecting

the subtlety of between-the-wars Paris. It is a heady and powerful

combination.

John France

|

|