|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads |

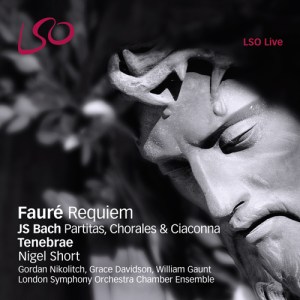

Johann Sebastian BACH

(1685-1750)

Chorale - Ach Herr, laß dein lieb Engelein [2:09]

Partita in D minor for solo violin, BWV 1004 (1720) - Allemande

[3:29]

Partita - Courante [2:10]

Chorale - Christ lag in Todesbanden [1:19]

Partita - Sarabande [3:32]

Chorale - Den Tod niemand zwingen kunnt [1:22]

Partita - Gigue [3:03]

Chorale - Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden [1:23]

Partita - Ciaconna (ed. Prof. Helga Thoene) [13:08]

Gabriel FAURÉ (1845-1924)

Requiem, Op. 48 (1893 version, ed. John Rutter) [36:40]

Gordan Nikolitch (violin); Grace Davidson (soprano); William Gaunt

(baritone); James Sherlock (organ)

Gordan Nikolitch (violin); Grace Davidson (soprano); William Gaunt

(baritone); James Sherlock (organ)

Tenebrae; London Symphony Orchestra Chamber Ensemble/Nigel Short

rec. live, 7 May 2012, St. Giles’, Cripplegate, London. DSD

Original texts and English translations included

LSO LIVE LSO0728

LSO LIVE LSO0728  [68:15]

[68:15]

|

|

|

For best results this disc is designed to be heard straight

through from start to finish. It preserves a programme devised

for the 2011 City of London Festival by Ian Ritchie, the Festival

director, and Gordan Nikolitch, the long-serving Leader of the

LSO. First performed in St. Paul’s Cathedral, the concert

was given again the following year in the more intimate surroundings

of St. Giles’, Cripplegate. The LSO Live microphones were

there to record it.

I should say straightaway that this CD includes one of the best

recordings of Fauré’s Requiem that I’ve heard.

There’s also some superb Bach playing by Gordan Nikolitch

but one aspect of the project may be controversial.

In 1720 Bach, who was then in the service of Prince Leopold

of Anhalt-Köthen, returned home from accompanying his master

on a three-month visit to Karlsbad to find that his wife, Maria

Barbara, who he had left in good health, had died suddenly.

The scholar, Prof. Helga Thoene believes that the D minor Partita,

and especially its extraordinary concluding Ciaconna, was written

in response to Bach’s grief at the passing of his wife

of some thirteen years. Examining the Partita and its companion

Sonata in A minor for solo violin, BWV 1003, she believes that

both are “based on inaudible chorale quotations”.

In a long and detailed booklet essay, which I won’t attempt

to summarise here, she states her theory that the chorale melodies

“employed as cantus firmi can be made audible by

prolonging the notes of the violin part with the aid of additional

instruments or voices.” This theory is put into practice

in this performance of the Ciaconna. Following through the premise

that the Partita represents a tombeau or epitaph for

Maria Barbara Bach, the remainder of the programme has been

constructed around the theme of death.

So, as can be seen from the track-listing, the first four movements

of the Partita are interspersed with Chorales, sung by Tenebrae.

I find this works pretty well and if one doesn’t like

the approach one can always skip those tracks and concentrate

on Gordan Nikolitch’s splendid performance of the solo

violin music. He’s searching in the Allemande and his

playing in the following Courante is lively. In the sprightly

Gigue he delivers some exceptionally clean and agile playing.

Controversy may arise with the conclusion of the Partita. In

the Ciaconna a small semi-chorus of eight singers - two per

part - sing fragments of lines from a variety of Chorales. All

the texts are given in the booklet. Nikolitch plays and thus

you can hear Prof. Thoene’s theory in action. Does it

work? Despite listening several times with, I hope, as open

a mind as possible, I don’t think it does. It’s

an interesting theory and I bow to Prof. Thoene’s expertise

as a Bach scholar. However, even if Bach did indulge in the

musical cryptography as she postulates, surely he didn’t

mean the code, when cracked, to be performed - and certainly

not as an accompaniment to the violin part? Bach pitted his

soloist against the intellectual rigour of the music - and assuredly

it is rigorous - but never intended the player to be pitted

against an accompaniment. Furthermore, if Bach had indeed written

an accompaniment to the solo part it surely would not have been

one in which the notes were sustained in the way that a choir

sings. The members of Tenebrae sing their lines beautifully

and with discretion but I’m afraid that, though the experiment

is an interesting one, I’m unsure it bears repeated listening.

I found the vocal contributions a distraction from Gordan Nikolitch’s

very fine playing and from Bach’s argument. What might

have been interesting would have been the inclusion of a separate

track of Nikolitch playing the Ciaconna in its standard form

so that one could then have this option and still hear the Partita

and the chorales as an imaginative prelude to the Fauré

Requiem.

The Fauré begins in the same key - D minor - as the Ciaconna.

In this performance the powerful opening chord follows the Bach

without a break, though it’s separately tracked so you

can listen to the Requiem in isolation if you wish. It’s

something of a jolt to move so suddenly from Bach to Fauré

but I find it works well. As I indicated above, the performance

of the Requiem is an exceptionally fine one. John Rutter’s

edition of the score, made in 1983, is used and throughout the

LSO Chamber Ensemble and organist James Sherlock provide distinguished

playing.

The singing of Tenebrae is flawless. The choir numbers twenty-four

singers (8/4/6/6) and the choir’s timbre, balance and

precision of ensemble is superb. For instance, in the Offertoire

we hear the duet between the alto and tenor parts as perfectly

balanced as you could wish. The sopranos bring an ethereal beauty

to the Sanctus - with Gordan Nikolitch, now rested after the

Bach, contributing a violin line of rapt purity. Purity is the

watchword, too, in the In Paradisum movement. Here the

sopranos float Fauré’s line tenderly and very beautifully.

The soloists, both members of Tenebrae, are excellent. Baritone

William Gaunt offers a good, clear and unaffected performance

of his solo in the Offertoire. If the word “unaffected”

seems like faint praise that’s not the intention; some

baritones try to be over-expressive in this work. I much prefer

the sort of straightforward, musical approach heard here. Grace

Davidson’s singing won’t please those who like to

hear a full-toned soprano sing the Pie Jesu with a fair

degree of vibrato. However, those who, like me, value purity

of tone and simplicity of utterance in this lovely solo will

find her very much to their taste. I enjoyed her poised and

pure singing.

Nigel Short directs a fine and expressive performance. If I

were being hyper-critical then I would have preferred him to

maintain the same speed in the Agnus Dei rather than

the marginal, unmarked, slowing that he makes at ‘Lux

aeterna’. However, that’s a very minor point in

the context of an excellent account. Although performances of

this work with a large choir and full orchestra have their place

my own preference is for this reduced scoring which allows one

to experience the intimacy of the piece to best advantage. This

Tenebrae version is one of the very best recordings of the 1893

score that have come my way.

The performances are presented in excellent sound; I listened

to the disc as a conventional CD. The documentation is very

thorough and my only complaint is that LSO Live continues to

use a minuscule typeface for their booklets. I truly found that

reading the booklet strained my eyes and Prof. Thoene’s

detailed note on the Bach is densely argued; it’s even

more difficult to follow her argument if one is struggling to

make out the words in the first place.

The concept of the programme is imaginative and thoughtful and

despite my reservation about the Ciaconna movement of the Bach

Partita I found this a stimulating experience. The conjunction

of Bach and Fauré works very well. As I hope I’ve

conveyed, the performances are superb.

John Quinn

|

|