|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

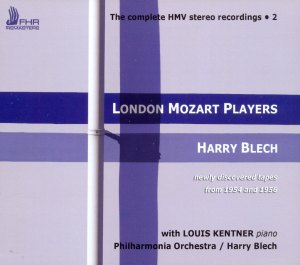

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756-1791)

Symphony no.36 in C Linz K.425 [23:45] (1)

Piano Concerto no.24 in C minor K.491 [34:08] (2)

12 Minuets K.568 [23:16] (3)

Louis Kentner (piano) (2)

Louis Kentner (piano) (2)

London Mozart Players (1, 3), Philharmonia Orchestra (2)/Harry Blech

rec. 22-23 December 1954 (1), 23-24 May 1959 (2), 4 December

1956 (3), Studio No. 1, Abbey Road, London

FIRST HAND RECORDS FHR15 [81:10]

FIRST HAND RECORDS FHR15 [81:10]

|

|

|

Not all that long ago I reviewed

a coupling of Schubert’s 4th and 5th

symphonies by the LMP under Harry Blech on Forgotten Records.

I gave an account of my personal recollections of Blech’s

conducting and of his long reign on the South Bank platforms.

So here I’ll just reiterate the main point that, during

the first decade of their activity, the LMP brought something

new to London concert life - an orchestra of approximately the

dimensions Haydn and Mozart would have heard and, equally importantly,

an exploration of the less well-known works of these composers.

By the time he retired, Blech had conducted all the symphonies

of both composers.

At the same time, Blech tended to use his small forces to propound

interpretations that, to today’s ears, seem essentially

romantic. We can hear this immediately in the introduction to

the “Linz” which is gravely paced and romantically

- almost Brahmsianly - coloured. The Allegro spiritoso

goes with a good deal of vigour while the Andante is expounded

with much breadth and considerable warmth. So far so good, but

the Minuet is not especially characterful and the Finale has

a rather portly gait for a “Presto”. In its majestic

way it convinces, but I’m not sure that the performance

delivers on its initial promise.

In the concerto Blech is conducting the Philharmonia. The opening

ritornello establishes no especial character. Louis Kentner’s

playing, however, is very strongly characterized. His tone is

lucent, but with slowish tempi, allowing the music to unfold

spaciously, the effect is of a dark lucidity. I find this very

interesting and the pianist deserved to work out his interpretation

with a kindred spirit. Blech follows him well enough while he

is playing, but in orchestral passages of any length his evident

tendency towards more suavely flowing tempi gets the better

of him, and Kentner has to re-establish his tempo every time.

By the finale they seem to have given up on each other and both

parties agree that sleepiness should be the name of the game.

Kentner’s own first movement cadenza is fascinating in

a slightly Medtnerish way and this little-recorded pianist probably

deserves investigation.

It is the 12 Minuets that make this record worthwhile. Blech

sees to it that each has its own specific character, lilting,

majestic, pompous and gently humorous by turn. He also has some

of the finest woodwind players on the London scene at the time

and he lets them enjoy themselves. In particular, every contribution

from the bassoonist Archie Camden is a delight. This, perhaps,

was what Blech and the LMP were all about: taking a set of “minor”

Mozart that nobody else back then, not even Beecham, would have

thought worth bothering about, and making each tiny piece a

delight.

A souvenir of a conductor and orchestra that had something of

its own to offer even in a city where the likes of Beecham,

Klemperer, Boult and countless more were regularly plying their

wares. A reminder of HMV in its halcyon days, too, with Berthold

Goldschmidt and Lawrance Collingwood named as producers. The

LMP performances were recorded in experimental stereo which

is seeing the light of day only with the present release. It

doesn’t sound its age. Blech’s left and right separation

of the first and second violins is a definite plus factor in

the “Linz”.

Christopher Howell

|

|