|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

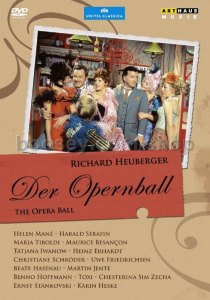

Richard HEUBERGER (1850-1914)

Der Opernball - operetta in three acts (1898)

Harald Serafin, Helen Mané, Maria Tiboldi, Tatjana Iwanow,

Christiane Schröder, Maurice Besançon, Heinz Erhardt,

Uwe Friedrichsen, Beata Hassenau

Harald Serafin, Helen Mané, Maria Tiboldi, Tatjana Iwanow,

Christiane Schröder, Maurice Besançon, Heinz Erhardt,

Uwe Friedrichsen, Beata Hassenau

Kurt Graunke Symphony Orchestra (Munich)/Willy Mattes

Kurt Graunke Symphony Orchestra (Munich)/Willy Mattes

Television Adaptation: Reinhold Brandes and Eugen York

Sound Format: PCM Stereo

Picture Format: NTSC/4:3

Subtitle Languages: German (original language), English, French

Region Code: 0 (All Regions)

ARTHAUS

ARTHAUS  101 628 [100:00]

101 628 [100:00]

|

|

|

Popular from its premiere through to the mid-twentieth century, the operetta

Der Opernball is probably the best-known work by the

composer Richard Heuberger. As familiar as the work has been

on-stage, it was filmed several times, specifically in 1939

(unfortunately without much of the score), 1956 and 1970. This

DVD is a transfer of the last film, which is based on a production

of the work in Munich. The 1970 film benefits from the close

angles and controlled sound of the studio in order to bring

the audience into the stage action. While the result may lack

the dynamic interaction with an audience, it still conveys the

immediacy of an effective theatrical production.

Perhaps less familiar to modern audiences than Johann Strauss’s

Der Fledermaus (1874) and Franz Lehár’s

Die Lustige Witwe (1905), Heuberger’s 1898 Der

Opernball falls aesthetically and chronologically between

those two works. With its use of waltzes and dance rhythms,

Der Opernball fits into the conventions associated with

operetta at the turn of the last century, but stands apart from

others of the time because of its cleverly plotted story.

The libretto for Der Opernball is a theatrical farce

from 1876 by Alfred Delacour and Alfred Hennequin, and features

a double deception between a pair of wives and their husbands.

This is complicated by the intrigues of Hortense, the maid of

one of the couples. In the good operatic tradition of testing

the faithfulness of spouses, the wives set up a deception to

intrigue their husbands, while trusting that the men will not

succumb to it. Here, the wives specifically plan assignations

with an unnamed countess, who plans to attend the opera ball

in a pink-hooded robe (the domino rose of the libretto) and

masked. When both wives decide to try their husband’s

virtue, the maid pursues the ruse herself, and the dénouement

involves three women in the same disguise, an anomaly that never

strikes the men as at all unusual. The complications ensue when

the husbands seem intrigued by the others’ wives and pursue

conversations in the private dining rooms at the ball. These

secluded rooms are the “chambre séparée”

that becomes the subject of a recurring waltz “Gehen wir

ins Chambre séparée” in the final act. The

complications are predictably temporary, with the couples resolving

their differences with remarkable speed and the maid winning

the nephew as her husband.

As to the film, the action is framed as the exchange between

painter Toulouse-Lautrec and his model Giselle, who set up the

story at the beginning and narrate the Finale as they reminisce

about memorable events of carnival season. This device is useful

in setting up the conclusion. While the painter and his model

talk about the morning after the ball, the filmed images are

manipulated to comic effect through the speeding up or slowing

of the images to bring out the humor of the expected duel and

reconciliation. This self-conscious treatment of the conclusion

works well in the film, which evokes some aspects of stop-action

found in Widerberg’s 1967 film Elvira Madigan.

Yet some other aspects of the film do not work as well. The

use of actors with dubbed voices is problematic: The acting

is good, and the singing laudable, but the synching is poor,

sometimes unintentionally comic. The latter is not the fault

of the DVD transfer, but a weakness of the original film. While

the lips do not always move seamlessly with the sound, the viewer

easily compensates for this minor failing. In this transfer,

the images are crisp and clear, with the resolution sufficiently

fine to allow the details in the painted flats of the drawing

room in the first act to call to mind paintings from the era.

A similar clarity is to be found with the sound, which is nicely

resonant.

All in all, the performances give a sense of the work, especially

through continuity which remains an attractive element of the

film The action moves smoothly between the scenes and plays

well into the timing necessary for the comic twists. In the

first part of the work, the somewhat sentimental aria “Man

liebt nur einmal auf der Welt” is nicely put across by

Harald Serafin (Paul), and its repetition is not unwelcome.

Yet its reprise is not allowed to halt the action, with the

character Feodora played by Beata Hasenau nicely upstaging Serafin’s

reverie by interrupting him and calling for a can-can. Other

numbers are memorable, such as the letter scene in the first

act underscored with the ensemble “Heute abend”,

in which the women Helen Mané (Angèle), Maria

Tiboldi (Marguerite), Tatjana Iwanow (Palmira) and Christiane

Schröder (Hortense) compose the messages to the husbands

and anticipate the excitement of the opera ball of the title.

The patter songs of the nephew Henri, portrayed by Uwe Friedrichsen,

suggest some aspects of Gilbert and Sullivan, especially in

the first act number “Ich habe die Fahrt um Kap Horn gemacht,”

with its use of nautical convention. Ultimately the “Chambre

separée” waltz recurs sufficiently to identify

its music with work, a feature that is not unwelcome. The timing

in the film allows it to work cogently within this interpretation

of the operetta.

The film also merits attention for the effective sets, which

make use of the graphic style of fin-de-siècle Paris

to reinforce the style implicit in the music. The conscious

evocation of Toulouse-Lautrec is brought to life through the

choreography, with its homage to the can-can immortalized in

art. Beyond the spirit of the period, the film captures the

spirit of Heuberger’s famous operetta. While this work

is now staged infrequently, the release of this film builds

a case for reviving Der Opernball so that modern audiences

might enjoy its charms.

James L. Zychowicz

|

|