|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

|

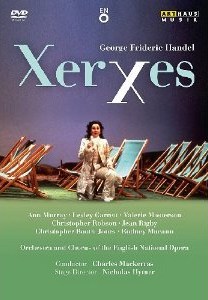

George Frideric HANDEL (1685-1759)

Xerxes (Serse) HWV40 - Opera in three

acts(1738) (sung in English)

Xerxes (Serse), A Persian king - Ann Murray (mezzo); Arsamenes,

Xerxes’ brother, Christopher Robson - (counter-tenor); Elviro,

Arsamenes’ often tipsy servant - Christopher Booth-Jones (baritone);

Ariodates, Commander of the army - Rodney Macann (bass-baritone); Romilda,

daughter of Ariodates, loved by Arsamene and who unknowingly bewitches

Xerxes by her singing - Valerie Masterson (soprano); Atalanta, secretly

loves Arsamene - Lesley Garrett (soprano); Amastris, forsaken by Xerxes

after his infatuation by Romilda and banished - Jean Rigby (mezzo).

Xerxes (Serse), A Persian king - Ann Murray (mezzo); Arsamenes,

Xerxes’ brother, Christopher Robson - (counter-tenor); Elviro,

Arsamenes’ often tipsy servant - Christopher Booth-Jones (baritone);

Ariodates, Commander of the army - Rodney Macann (bass-baritone); Romilda,

daughter of Ariodates, loved by Arsamene and who unknowingly bewitches

Xerxes by her singing - Valerie Masterson (soprano); Atalanta, secretly

loves Arsamene - Lesley Garrett (soprano); Amastris, forsaken by Xerxes

after his infatuation by Romilda and banished - Jean Rigby (mezzo).

English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus/Sir Charles Mackerras

rec. live, English National Opera, 1988

Stage Direction: Nicholas Hytner

Set Design: David Fielding

Subtitle Languages: English (original language), French, German,

Spanish, Italian, Dutch

Picture Format: 4:3. DVD Format, DVD 9, NTSC. Sound Format: PCM

Stereo

ARTHAUS MUSIK 100 077

ARTHAUS MUSIK 100 077  [186:00]

[186:00]

|

|

|

I sometimes think that a Handel renaissance in the UK has been

on the horizon, or at least in sight, since the 1980s. Way back

then, with the help of CD recordings on Philips, the Verdi renaissance

was well under way whilst the Pesaro Festival accelerated that

of Rossini’s works. Somehow the virtues of Handel’s

operatic works have largely languished. They seem to have lacked

a committed champion with clout. Yes, his operas tend be long

and somewhat static, but also I suspect the gender mix-ups are

seen as an audience deterrent. These are inherent in all operatic

works of the period with roles written expressly for castrati.

In this one the gender confusions are increased beyond the normal

run with the King being sung by a mezzo en travesti, his brother

by a counter-tenor and Xerxes’ forsaken lover, Amastris,

re-appearing in man’s attire. In this production, in wonderfully

inventive and colourful sets by David Fielding, the costumes

are sensible without being exact to a period, particularly in

respect of Romilda and Atalanta, the two women in the lives

of the two brothers.

Since this production was first seen in London in 1985, and

recorded for transmission on television three years later -

not ten years as the booklet states - Handel’s operas

have had a very minor resurgence in Britain. This has often

been at the summer country house festivals and at the Buxton

Festival, although even there the staging of certain of the

composer’s oratorios seems to find more favour. As I write

in 2012, there have been more positive signs. Opera North recently

presented Giulio Cesare (see review), Welsh National

Opera plan a staging of the oratorio Jeptha for its autumn

season at Cardiff, and the associated tour, and the Royal Northern

College of Music in Manchester are staging Xerxes (see

review). Prior to the

latter production, the last time the college presented any Handel

was Alcina twenty or more years ago. That was one of

two productions the college featured specifically to showcase

the rapidly emerging talent of Amanda Roocroft who went from

College direct to a contract with Welsh National Opera. Nor

should we forget Glyndebourne’s recent effort with a hailed

Giulio Cesare. These more recent swallows do not make

a spring, but several professional companies scheduling Handel’s

works, and now one of the UK’s leading conservatories

… well, that promised renaissance might just be getting

nearer.

Nicholas Hytner's highly innovative production of Xerxes

won the coveted Laurence Olivier Opera Award and this video

resurrection of the performance might just be a watershed rather

than just another British swallow. This 1988 performance

features some of the outstanding English-speaking singers around

at that time. All are good in their roles and if there are a

few moments of vocal imperfection they are more than compensated

for in outstanding acting and decorated singing. The mezzo-sopranos

Ann Murray and Jean Rigby are quite magnificent in their sung

and acted portrayal. If the sopranos Valerie Masterson and Lesley

Garrett don’t quite match them it is by a small margin,

with the latter acting the role with every facial expression

imaginable, and then some, whilst singing with a clear lyric

quality. The dark tones of Rodney Macann are sonorous whilst

Christopher Booth-Jones does not over-act the role of Elviro,

as can so easily be the case. The counter-tenor Christopher

Robson does his best without my yearning for the more creamy

tones found among some European singers of the genre.

Having lauded the virtues of the direction, sets, costumes and

singing, I have to find some greater superlatives for the contribution

of Sir Charles Mackerras’s conducting. With a trimmed-down

band he manages a near Baroque rendering of his own erudite

edition of Handel’s even longer score. It is too rare

to find practice and scholarship so closely entwined, albeit

perhaps one should not be surprised by the man who did so much

to bring the operatic works of Leos Janáček before

West European audiences and British ones in particular.

Robert J Farr

|

|