|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound Samples & Downloads

|

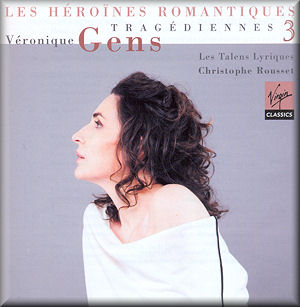

Tragédiennes 3: Les Héroïnes

Romantiques

Étienne-Nicolas MÉHUL (1783-1817)

Ariodant (1799): Quelle fureur barbare !... Mais, que dis-je ?...

O des amants le plus fidèle [10 :06]

Rodolphe KREUTZER (1766-1831)

Astyanax (1801) : Ah, ces perfides grecs … Dieux, à qui

recourir [3 :20]

Antonio SALIERI (1750-1825)

Les Danaïdes (1784) : Ouverture [4 :47]*

Christoph Willibald GLUCK (1714-1787)

Iphigénie en Tauride (1779) : Non, cet affreux devoir –

Je t’implore et je tremble [3 :17]

François-Joseph GOSSEC (1734-1829)

Thésée (1782) : Ah ! faut-il me venger … Ma rivale

triomphe [3 :19]

Giacomo MEYERBEER (1791-1884)

Le Prophète (1849) : Ah, mon fils [3 :55]

Auguste MERMET (1810-1889)

Roland à Roncevaux (1864) : Prête à te fuir … Le soir pensive

[6 :21]

Hector BERLIOZ (1803-1869)

Les Troyens (1858) : Entrée des constructeurs – Entrée

des matelots – Entrée des laboureurs [3 :57]*, Ah !

Je vais mourir… Adieu, fière cité [6 :13]

Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835-1921)

Henry VIII (1883) : O cruel souvenir ! … Je ne te

reverrai jamais [8 :32]

Jules MASSENET (1842-1912)

Hérodiade (1881) : C’est Jean ! … Ne me refuse pas

[4 :10]

Giuseppe VERDI (1813-1901)

Don Carlos (1867) : Toi qui sus le néant des grandeurs

de ce monde [9 :33]

Véronique Gens (soprano) [except items marked *]

Véronique Gens (soprano) [except items marked *]

Les Talens Lyriques/Christophe Rousset

rec. 30 June – 5 July 2011, Ircam, Paris

Booklet includes original texts with English and German translations

VIRGIN CLASSICS 0709272 [67:49]

VIRGIN CLASSICS 0709272 [67:49]

|

|

|

Have I been missing something? This is the third volume of a

series that began from the dawn of French opera, with Lully,

Campra and Rameau, and now reaches its romantic flowering in

the later 19th century. Common to all three discs

is the presence of Gluck; French opera, as can be seen from

the names of Gluck, Salieri, Meyerbeer and Verdi, is intended

in the broad sense of opera in French.

An ambitious programme for a single singer. I can only say that,

as far as the present end of the operation is concerned, Véronique

Gens is triumphantly in command of it all. Her voice has a natural

sweetness that may seem small until we realize that she can

expand excitingly – as in the climax of the Verdi – without

a trace of hardening. She can also employ her chest tones without

rasping. Above all she has weighed every word, every phrase,

to bring maximum meaning to what are almost exclusively dramatic

scenas rather than strict arias. Given that the period-instrument

band exploits the piquant sound of its wind instruments in the

quiet passages and invests the agitated ones with a whiplash

attack and a sizzling precision that even Toscanini would have

been proud of, the music is given every possible chance.

It is here that some doubts arise. Maybe for those who have

followed the whole enterprise from its first volume the whole

is greater than the sum of its parts. The parts that open volume

3 come from a period which did not produce many French operas

that have taken a firm place in the repertoire. Méhul, Kreutzer

and Gossec are all names one knows from the history books. Or,

at least, we remember that Méhul wrote an overture that Beecham

was fond of, Kreutzer – yes, that Kreutzer – was the

dedicatee of one of Beethoven’s violin sonatas and Gossec wrote

a charming piece called Tambourin that used to be very

popular. In theory one can only welcome the opportunity to know

more about them. Would a complete opera have made a better case

for them, or buried them for good? The trouble is that they

seem stylistically interchangeable. Adept at providing dramatic

recitation with some colourful orchestral touches, they fail

to cap it with a memorable tune you take away with you. And,

if they do try, they fall back on banality. It can be described

as “functional” music, the late 18th century equivalent

of a film soundtrack. With opulent staging I’m sure it “worked”,

and maybe still would. Which is why I wonder if a complete opera

might not have made a better case. Gens certainly makes a strong

case for being chosen as the leading soprano in any such recording

that might be made.

The interesting thing about this group is that Gluck, as far

as this aria from this opera goes, seems no better than the

others. As for the Salieri overture, it sounds like a Hoffnung-style

tease, a manic switch of Mozart quotations dangled before us

and whisked away while we still have the source on the tip of

our tongues. Well, there’s one you’d have to get… only the Salieri

quote precedes the Mozart “source” by two years, giving rise

to interesting reflections.

We now step forward a generation. Meyerbeer’s “Le Prophète”

was actually a repertoire opera for a substantial part of its

lifetime. Famed for its grandiosity, the piece here is tender,

lyrical, and brings a breath of genuine inspiration to the programme

at last. Mermet was new to me entirely. His aria is a well-written

affair with a principal lyrical tune that comes dangerously

close to Adophe Adam’s “Cantique de Noël”. I have no idea, though

whether Adam’s pretty bit of Christmas tinsel had reached its

present-day ubiquity by 1864.

The Berlioz orchestral piece is a surprisingly sprightly affair

for a grand opera that is mostly very grand indeed. Dido’s monologue

and aria are another matter, full of tragic depth and heartfelt,

if not heart-on-sleeve – emotion. Gens interprets it strongly

with a strong awareness of its essentially classical manner

of utterance.

The Saint-Saëns piece is a lyrical, tender outpouring with a

well-coloured orchestral part. It is not an obvious smash-hit

like that aria from “Samson et Dalila”, but it is possibly

equal to Dalila’s other two arias from the same opera, which

is no mean thing. A modern complete recording is probably needed,

preferably with Gens in the role of Catherine d’Aragon.

The Massenet extract suffers from the problem of many later

19th century operas that, while not through-composed

in a strictly Wagnerian sense, they are nonetheless continuous.

They have extractible “arias” in the sense that sometimes one

singer takes the stage alone for five minutes or so, but they

are not, and the present aria is not, satisfactorily-shaped

individual entities with a beginning, middle and end. This is

not intended to detract from a piece that is surely finely effective

in its context. It just sounds a bit inconclusive here.

Can a piece have a beginning, middle and end, and at the same

time form part of a larger overall design? Meyerbeer and Berlioz

seemed to show that it can. Verdi, just in case you haven’t

guessed it, gives a lesson to them all. How to forge a meaningful

accompaniment, how to make each section follow on inexorably

from the last and, finally, how to provide that essential ingredient

of a great evening in the opera house, a climatic phrase that

just knocks you for six. Gens rises to it all splendidly.

Put like this, it sounds as if I’m suggesting Gens would have

done better to record a disc of popular Verdi arias and have

done with it. No doubt she would have done that well, but I’m

very glad she opted, instead, to use her talents for the purpose

of extending our knowledge. Even if a few of the pieces here

elicit the response, “Well, so that’s what it’s like..”, the

singing and the orchestral collaboration ensure there’s never

a dull moment. A major project from a major artist.

Christopher Howell

|

|