|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

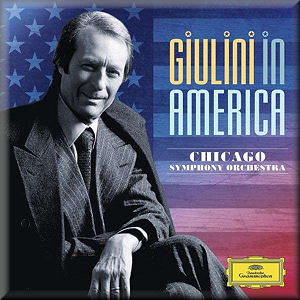

Giulini in America

CD 1

Franz SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

Symphony No.4 in C minor, D.417 - "Tragic" (1816) [32:05]

Antonín DVORÁK (1841-1904)

Symphony No.9 in E minor, Op.95 "From the New World" (1893) [45:59]

CD 2

Franz SCHUBERT

Symphony No.9 in C, D.944 - "The Great" (1826) [59:09]

Sergei PROKOFIEV (1891-1953)

Symphony No.1 in D, Op.25 "Classical Symphony" (1916) [14:33]

CD 3

Antonín DVORÁK

Symphony No.8 in G, Op.88 (1889) [40:18]

Modest Petrovich MUSSORGSKY (1839-1881)

Pictures at an Exhibition (1874) (orch. Ravel, 1922) [34:36]

CD 4

Gustav MAHLER (1860-1911)

Symphony No.9 in D (movts. 1-3) (1908-09) [63:08]

CD 5

Gustav MAHLER

Symphony No.9 in D (movt. 4) [25:28]

Franz SCHUBERT

Symphony No.8 in B minor, D.759 - "Unfinished" (1822) [28:00]

Benjamin BRITTEN (1913-1976)

Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, Op.31 (1943) [24:23]

Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Carlo Maria Giulini

Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Carlo Maria Giulini

Robert Tear (tenor), Dale Clevenger (horn) (Britten)

rec. Chicago, Orchestra Hall, April 1977 (Dvorak 9, Schubert 9, Britten), March 1978 (Schubert 4, Dvorak 8, Schubert 8), Chicago, Medina Temple, April 1976 (Prokofiev, Mussorgsky, Mahler).

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 477 9628 [5 CDs: 78:03 + 73:39 + 74: 54 + 63:08 + 78:01]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 477 9628 [5 CDs: 78:03 + 73:39 + 74: 54 + 63:08 + 78:01]

|

|

|

This is ‘Giulini in America II’, the other Deutsche Grammophon box in a pair of specially priced releases being their complete recordings of the conductor with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. The latter is 6 CDs, this Chicago set a nicely packaged 5, and all for about the price of a single full-price disc. Collectors interested in the Chicago SO in particular should also acquire the EMI’s ‘The Chicago Recordings’ which also has some superb Mahler, as well as a Bruckner 9th Symphony to cherish. Many other recordings can be found on the BBC Legends label.

Carlo Maria Giulini’s career started as a viola player in an Italian orchestra, and he experienced conductors such as Bruno Walter, Wilhelm Fürtwangler and Otto Klemperer at first hand. He made his American debut as a conductor in 1955 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and was principal guest conductor with them from 1969 to 1972, working alongside Sir Georg Solti. Marc Bridle’s obituary for Giulini can be found here, and while we’re dishing out hyperlinks you can find a review of the individual release of Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 and Mahler’s Symphony No.9 here.

With such a plethora of classic recordings from a crack orchestra under one of the most distinguished conductors of the last century and at such a minimal financial outlay, the cliché ‘what’s not to like?’ has to apply here. These are all analogue recordings from the 1970s, but the sound quality is very fine indeed, and I know enough people who love that warmth from such now ‘mature’ recordings to value the fact that this quality is preserved on these CD transfers – indeed, I am one of their number, being old enough to remember being unable to afford them when they were first released. As for style, Giulini’s Schubert is big-boned, but not overblown. The trend for a more chamber-orchestra feel in these pieces was to come later, but there is no lack of intimacy in the expression of the opening of the Andante second movement of the Symphony No.4. The opening of the Menuetto is uncompromisingly forceful, but this weight contrasts with Schubert’s witty wind writing, and Giulini’s tempos are never heavy in their tread. The same goes for the Symphony No.9 on CD 2, though there are a few minor intonation issues. Ears today are perhaps less used to the vibrato in the playing on these recordings, but this is a textural and period quality of the orchestra as a whole, and there’s nothing ugly here. One funny side effect of this however occurs 3 minutes into the first movement of the Symphony No.9 with the clarinets, which now sound like soprano saxophones – Schubert meets Nyman in a temporal anomaly. Giulini’s phrasing is broader at times than we normally hear today, though the articulation is also filled with moments of utmost transparency. The Chicago brass are given plenty of space to develop their power in the first movement of this symphony, and each time you hear one of those big tuttis the sense is of generosity of spirit and a heightening of drama rather than of anything dated or ill-conceived. I particularly like the Scherzo, with its depth of string sound and big sense of rhythmic bounce. To round off the Schubert, CD 5 has the Symphony No.8 which was coupled with Mahler’s Symphony No.9. This is another potently dramatic performance which brings out the enigmatic darkness of the piece, as well as the lyrical beauty of its dances – brooding and poignant nostalgia live together cheek by jowl in the first movement, and I know no other recording which brings out so much of the hollow anguish felt by the composer. As a result, the darkness to light relief of the Andante con moto is palpable, though this too remains a fragrant melody which exists under shadows of remorse and regret – sustained and weighty in the Klemperer mould, and none the worse for that. This is artful Schubert with genuine power and memorable impact – chocolate box prettiness concealed under a blackened and rotting wreath of mortality and human fragility.

Having started chronologically in terms of composer’s dates of birth, it would make sense to move on to Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. This is still something of a demonstration quality recording, with every detail of Ravel’s orchestration picked out in fine detail. This is not always to its advantage, and some of the percussion effects can sound a little crass as a result, but that’s not Giulini’s fault. He hears this work as more of an operatic drama without singers rather than an orchestral showpiece. His measured tempi take something from the impressive brilliance of the piece as a concert work, but give back so much more in terms of character. Each movement is, as it should be, a pictorial vignette filled with descriptive atmosphere, and the rewards are rich indeed. Instrumental solos are marvellous of course, from the trumpet in particular, but the saxophone in Il vecchio castello also deserves a mention. Every movement comes up trumps, from the darkness of Bydlo and terrors of the Catacombae to the silly frivolousness of des petits poussins this is still one of the best Pictures at an Exhibition ever recorded.

Antonín Dvorák is up next, and it would appear Giulini’s recordings of the Symphony No.8 and Symphony No.9 ‘From the New World’ have been left behind somewhat. The latter appeared on a DG Galleria budget release back in 1990, but neither of these recordings seem to have been reissued since, nor do they get a mention in The Penguin Guide 2010. This is a shame, since the Symphony No.8 has a great deal to offer. Measured in its tempi but rich in sonority and inner detail, the Symphony No.8 has all its dramatic elements superbly intact, and everything from those poignant little melodic figures to the ‘big tune’ moments are all given true warmth of expression by the Chicago players. The Symphony No.9 is better recorded but was considered arguably less exciting than an earlier recording Giulini made with the Philharmonia Orchestra on the HMV label, and the general opinion of these particular Dvorák symphony recordings might once have been ‘not quite as good as Kertesz/Kubelik/Karajan’. Today we are spoilt for choice. My own affections with this music are with the Czech Philharmonic and Vaclav Neumann on the Supraphon label, simply because they seem to breathe the same air as Dvorák both literally and metaphorically. The character of the Chicago orchestra with Giulini is wonderful and very much worth having as part of this set, but these recordings don’t quite take me to those woods and fields in quite the same way as Neumann. Perhaps it is Giulini’s sense of detachment – admirably allowing the music to speak for itself but lacking that last ounce of dramatic impetus, of freedom and flexibility, which leaves these recordings just short of the best of the rest. You certainly won’t be disappointed by these performances, but neither are they the last word on these symphonies.

Giulini’s Chicago recording of Mahler’s Symphony No.9 has long been highly regarded and, with plaudits including a Grammy award is of justly classic status. Giulini takes broad tempi in general with this symphony and this is apparent from the outset, building a tremendously powerful structure over nearly 32 minutes in a first movement which normally comes in well under 30. As with the Mussorgsky, the impressiveness is not so much in orchestral spectacle, but rather in a kind of psychology which works its way into the imagination – both as an immediately involving and fascinating theatre of the infinite and the unique, as well as over that lengthy span of time which involves cumulative emotion and memory. There are possibly some balance issues with the recording, which favours winds and brass over strings, but all sections of the orchestra make enough impact to prevent this being a real issue for the work in its entirety. Climaxes are overwhelming, and the sense of emotional depth is potent throughout the work, even in places where you’d expect it least such as the second movement ländler, which is by no means a light skip through sunlit fields. The impact of the emotional heart of the third movement has been struck with more passion elsewhere, and I would agree with some commentator’s opinions that the final Adagio is richer in Italianate lyricism than deeply explored emotion dug from the depths of the soul. This doesn’t mean this is not a marvellously expressed and moving statement, but other conductors such as Bernstein and Karajan wring more from the score earlier on. One of my favourites of the more vintage generation of recordings of this work is that from 1964 with Sir John Barbirolli and the Berlin Philharmonic on EMI, and in this one hears where even just a little greater freedom with tempi, just those moments of heightened anticipation can bring yet more stunning results. Giulini’s ‘long view’ means that the arrival at the climax and final apotheosis of this movement is where it’s ‘at’ however, so again this is still a Mahler 9th Symphony I would not want to be without, and the rewards by far outweigh any subtle nuances preferred in other recordings.

Prokofiev’s brief but brilliant Symphony No.1 is performed here with poise and elegance, and Giulini’s restraint creates a different atmosphere to the one we’re more used to. The urbane and good natured ‘Classical’ symphony can have something of Prokofiev’s later brittle and nervous tensions if driven at full speed, but even the final Molto vivace is given a more relaxed and breezy air than one of an orchestra on the edge of its collective seat. I must say I find this approach quite refreshing, with every detail in the opening Allegro allowed its due weight rather than everything being transitional. The second movement is marked Larghetto, and builds nicely from almost nothing to create a fine pastoral mood, and the Gavotta could be made for equestrian dressage – or maybe that’s just my strange imagination at work. Either way, it has the feel of a dance designed for something with longer legs than you or I.

Benjamin Britten is about as contemporary as Giulini went with his repertoire, and we’re fortunate to have this fine recording of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings op.31. Robert Tear is an authoritative soloist, and principal hornist of the Chicago SO Dale Clevenger is on stunning form. The atmosphere in the William Blake Elegy: “O Rose, thou art sick” is beautifully remote and at times unearthly, the feeling of energetic life the obverse in Ben Jonson’s “Queen and huntress, chaste and fair.” This is a recording I’ve previously come across in another Deutsche Grammophon collection, ‘The Chicago Principal’ 472 798-2, which is a remarkable showcase for the orchestra’s leaders and soloists. All of the texts for the Serenade are provided in the booklet for this ‘Giulini in America’ release in English, French and German.

To sum up, there has never been a better time to acquire Carlo Maria Giulini’s distinguished recordings in a veritable bumper crop of bargain slimline packages, and this Chicago set is a ‘must have’ for collectors and newcomers alike.

Dominy Clements

|

|