|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

Fryderyk CHOPIN (1810-1849)

Nineteen Waltzes

1. A-flat Major, (Brown-Index 21) [1:26]

2. D-flat Major, Op. 70, No. 3 [2:53]

3. B Minor, Op. posth. 69, No. 2 [3:45]

4. E Major, (Brown-Index 44) [2:38]

5. E-flat Major, (Brown-Index 46) [2:31

6. E Minor, (Brown-Index 56) [2:53]

7. E-flat Major, Op. 18 [5:56]

8. G-flat Major, Opus posth. 70, No. 1 [2:27]

9. A-flat Major, Opus posth. 69, No. 1 [3:56]

10. A Minor, Op. 34, No. 2 [5:13]

11. A-flat Major, Op. 34, No. 1 [5:56]

12. F Major, Op. 34, No. 3 [2:42]

13. E-flat Major, (Brown-Index 133) [2:05]

14. A-flat Major, Op. 42 [4:05]

15. F Minor, Opus posth. 70, No. 2 [3:28]

16. A Minor, (Brown-Index 150) [2:49]

17. C-sharp Minor, Op. 64, No. 2 [3:41]

18. A-flat Major, Op. 64, No. 3 [3:52]

19. D-flat Major, Op. 64, No. 1 [2:03]

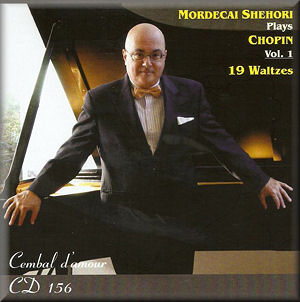

Mordecai Shehori (piano)

Mordecai Shehori (piano)

rec. October 2010, Las Vegas

CEMBAL D’AMOUR CD156 [63:58]

CEMBAL D’AMOUR CD156 [63:58]

|

|

|

This sequence of Chopin waltzes was recorded in the first two

weeks of October 2010 by Mordecai Shehori, and it demonstrates

his investigative mind at work once again. He’s not a musician

to allow established protocol to hinder a new look either at

source material or at matters of presentation. So, quickly dispatching

the question of opus numbers in a booklet note entitled ‘The

Pointlessness of Opus Numbers as a Guide to a Composer’s Development’,

he has arranged the sequence chronologically. He has also investigated

the ‘Julian Fontana’ versions of four waltzes, Op. 69 Nos 1

and 2, Op. 70 Nos 1 and 2. Fontana, a friend of the composer,

copied Chopin’s music, and it was he who saw these four waltzes

to paper; they survive only in sketch-like form. Shehori has

incorporated the early sketch version into the Fontana, usually

in the form of the last repeat. His notes underline Shehori’s

commitment to this practice.

The proof as ever, is in the eating. Shehori is on record as

decrying a lack of textual fidelity by even the greatest pianists.

His own approach is faithful and imaginative. His D flat major

Op.70 No.3 has great tenderness, and a warmth that, say, Rubinstein

never truly sought to cultivate in this work, remaining as he

did more austere and extrovert than Shehori’s more introspective

limpidity. Shehori is certainly more inclined to explore the

rubato and rhythmic implications of the B minor (that posthumous

Op.69 No.2) than Rubinstein or even Lipatti, whilst in the E

flat major (Brown Index 46) he investigates the Tyrolean yodel

that Chopin infiltrated into the music. Shehori’s booklet note

includes a passage on this matter and it makes for engaging

reading, and indeed listening, in the light of it.

In the E flat major Op.18 Shehori shows a distinct independence

from Rubinstein in his classic 1954 studio recording, being

more athletic in accenting and dynamic in phrasing – indeed

more explosive all round. His approach in the G flat major Op.

posth. Op. 70 No.1 is quite measured. He is not much pursuant

of the kinds of colour that Rubinstein and Lipatti found here,

rather more on the structural and rhythmic bases of the music.

Nor does he seem much to endorse the ‘L’Adieu’ element of the

A flat major Op. posth. Op.69 No.1, given that his tempo is

quite brisk and that his interest centres of the harmonic steps

in the left hand, which are explored to advantage. He emphasises

details such as this, which other pianists are apt to conjoin

to an all-purpose ‘beautiful tone’ – not that Shehori’s tone

is anything but highly attractive.

He does prefer a rather ‘sec’ approach to the A flat major Op.34

No.1. His avoidance of metricality, as well as a broader tempo,

gives the music a light, tripping immediacy, reinforced by the

quite immediate recorded quality. It’s anything but grand seigniorial.

Shehori’s little nagging left hand accenting illuminates the

A flat major Op.42; this deft harmonic pointing is itself one

of Shehori’s points, as are a well judged control of rubati

and accelerandi.

This enterprising, very personal approach will win Shehori admirers.

His slant is sometimes unusual, always thoughtful, and he has

a particular gift for generating intensity and spontaneity in

the recording studio.

Jonathan Woolf

|

|