|

|

|

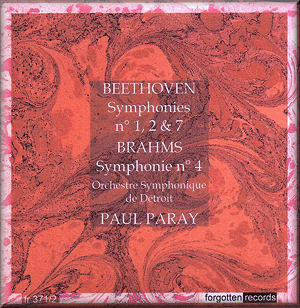

CD: Forgotten

Records

|

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21 (1800) [22:45]

Symphony No. 2 in A major, Op. 36 (1802) [31:28]

Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92 (1812) [35:56]

Johannes BRAHMS (1833-1897)

Symphony No. 4 in E major, Op. 98 (1885) [39:39]

Detroit Symphony Orchestra/Paul Paray

Detroit Symphony Orchestra/Paul Paray

rec. February 1953, Masonic Temple Auditorium, Detroit (Op. 92);

March 1956, Orchestra Hall, Detroit (Brahms); January 1959, Ford

Auditorium

FORGOTTEN RECORDS FR371/2 [54:16 + 75:38]

FORGOTTEN RECORDS FR371/2 [54:16 + 75:38]

|

|

|

Gone are the days when record companies put their addresses

on the back of the LP cover. Now the only way to contact most

of them is by an anonymous email link on a website. Such is

progress. Judging from the forgotten records website – trendy

lower case, be it noted – the company is French and is dedicated

to bringing neglected historic issues back into circulation

in the best possible transfers. If the venture doesn’t work

it won’t be because the presentation was too costly, as there

isn’t any to speak of. There are no notes accompanying this

double CD issue, though the back of the box does carry useful

information about the recordings’ origins, as well some interesting

internet links.

Richard Wagner is said to have described Beethoven’s Seventh

Symphony as “the apotheosis of the dance”, but I’ve never quite

bought it myself. The symphony possesses an undeniable and irresistible

rhythmic life, but it doesn’t sound like dance music to me.

With that in mind, this reading, set down getting on for sixty

years ago by French conductor Paul Paray (1889-1979) comes as

close as any to convincing me. It is a remarkably fleet-footed

performance, with spring in the rhythm at all times. This applies

equally to the second movement, given here in a flowing tempo

which might just have seemed matter of fact were it not for

the masterly control of the terraced dynamics leading to the

first fortissimo. I’m impressed, too, by how agitated the music

becomes when the accompanying triplets turn into semiquavers.

All this is heard after a marvellous first movement, the slow

introduction suitably weighty but followed by an Allegro that

brilliantly maintains momentum, the difficult dotted rhythm

always perfectly articulated, and with a control of pulse, sometimes

edging forward, sometimes holding back, that seems perfectly

natural and uncontrived. The end of the movement – superb horns

– is as jubilant as one is likely to hear it. The scherzo demonstrates

similar virtues, and the passage leading to the main climax

of the finale has the Detroit musicians playing at white heat.

For my money, not even Carlos Kleiber’s account of the finale

is more incendiary than this.

This performance has already been available on CD. I haven’t

heard that transfer, and so can’t compare it to this one, but

nobody would expect state of the art sound from 1953, and it’s

easy to live with occasional harshness on high violin lines

and unduly thunderous timpani. The mono recording is perfectly

acceptable otherwise, and the performance is such that you quickly

forget the sound. Three almost imperceptible clicks in the scherzo

remind the listener that this has been taken from an LP; they

induced something like nostalgia in this unconditional CD fan.

I owned this performance on the Wing label as a teenager. I

had very fond memories of it and they have been confirmed in

this transfer. The rest of the collection doesn’t live up to

it, however. The First Symphony was recorded six years later

and is in stereo. The sound is fuller and richer, though no

less clear and analytical, but the source seems to have been

in less good condition, as there are momentary imperfections

and dropouts, especially in the first movement. The performance

of the Seventh was characterised by rhythmic life and flexibility,

whereas this First seems to pursue rhythmic rigour at the expense

of expressiveness. The performance as a whole is rather hard

driven, an impression underlined by the lack of quiet playing.

The slow movement, for example, contains many a piano

indication, and not a few at pianissimo, but Paray seems

unwilling to impose these on his players. The scherzo is rigid

and unsmiling, and Paray proposes no relaxation of tempo or

atmosphere for the trio section. The finale goes at a cracking

pace and the orchestral playing is superbly unanimous, as indeed

it is throughout. This is a fine performance technically, but

Beethoven’s essential humour and high spirits are in short supply.

The Second Symphony has similar virtues and similar faults.

The first movement is certainly an Allegro with plenty of brio,

and rather as he does in the Seventh, Paray whips the orchestra

into a near-frenzy at the end of the movement. The slow movement

is perfectly paced but sadly lacking in charm, whereas the scherzo

is very steady, with once again, no broadening of tempo for

the trio. The finale is brilliantly played, with all sections

of this magnificent orchestra shown of at their best. Once again

though, a certain reluctance to play softly, rather brutal phrasing

from time to time, as well as relentlessness in matters of pulse,

make for a Beethoven Second that is frankly not much fun. Listen

to the finale, for example, where Beethoven’s genius fashions

something brilliant out of a rather absurd theme.

Exposition repeats in the Beethoven symphonies are not observed.

There are no repeats in the Brahms, and the performance is disappointing.

The recorded sound, in mono again, is distant and ill defined,

with the woodwind, especially, very recessed. The reading is

dull, with playing that is technically very fine but musically

routine. The opening of the first movement lacks passion and

tenderness, and the end is not the rather horrifying homecoming

it should be. The slow movement and scherzo do not command attention,

and the finale opens with a first trombone so loud and brash

that one almost wants to abandon the performance there and then.

William Hedley

|

|