|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

|

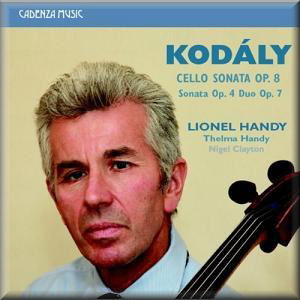

Zoltan KODÁLY (1882-1967)

Sonata for solo cello, op. 8 (1915) [32:52]

Sonata for cello and piano, op. 4 (1910) [17:52]

Duo for violin and cello, op. 7 (1914) [25:31]

Lionel Handy (cello), Thelma Handy (violin), Nigel Clayton (piano)

Lionel Handy (cello), Thelma Handy (violin), Nigel Clayton (piano)

rec. March 2010, PATS studio, University of Surrey (op. 4 and op.7);

May 2010, St. Andrews Church, Toddington (op. 8). DDD

CADENZA MUSIC CACD 0810 [76:45]

CADENZA MUSIC CACD 0810 [76:45]

|

|

|

Bach’s six Suites for unaccompanied cello form the basis of

the cello repertoire, the equivalent to the Old Testament for

cellists. The solo cello repertoire languished somewhat in the

nineteenth century, but in the century following quite a number

of composers wrote works for the instrument, including Ernest

Bloch, Benjamin Britten, Gaspar Cassadó, Paul Hindemith, Aram

Khachaturian, and Sergei Prokofiev. The work most likely to

be regarded as the New Testament, however, is the Sonata for

solo cello by Zoltan Kodály.

Kodály completed this work in early 1915, during a period of

intense research into Hungarian folk music, in which he collaborated

with Bela Bartók. Hungarian themes had been used in classical

compositions before, notably by Haydn, Brahms and Liszt. The

material they had used, however, was a pseudo-folk urban “gypsy”

style revolving around the alternately fiery and sentimental

czárdás. Kodály and Bartók discovered and recorded authentic

material that was a lot more raw and fiery. Kodály taught himself

the cello in his teens, so the solo Sonata also drew on his

inside knowledge of the instrument. The Sonata for solo cello

combines the volatile folk-based material with highly virtuosic

cello writing in a work that is a classic in the modern cello

repertoire.

Lionel Handy has studied with Janos Starker and Pierre Fournier,

and for ten years was principal cellist with the Academy of

St. Martin-in-the-Fields. This performance of Kodaly’s op. 8

Sonata shows him to be a well organised player who enters wholeheartedly

into the composer’s passionate idiom. From the declamatory opening

the first movement moves through many highly contrasted episodes.

Handy brings out the question-and-answer writing well, and lower

strings of his instrument have a rich resonance. The Adagio

has an impressive eloquence and the left hand pizzicato is very

well done, as was the alternation of pizzicato and arco in the

extremely difficult finale. Handy’s assurance, both technical

and interpretive, is most impressive.

Kodaly’s early Sonata for cello and piano dates from 1909, and

is a rather more accessible work than the solo sonata. The influence

of Debussy shows in the piano part, and in the use of short

motifs and rather elliptical phrasing, particularly in the second

movement. The sonata for cello and piano by Shostakovich also

comes to mind, although that was not composed until 1934. Handy

and pianist Nigel Clayton give an accomplished performance of

this sonata.

Handy is joined by his sister Thelma Handy in a performance

of the Duo for cello and piano, op. 7. Like the solo cello sonata

this employs a folk-inspired idiom, with quite an improvisatory

quality. There were some echoes also of the English folk music

school, particularly E. J. Moeran’s String Quartet. The Handys

are very well-matched tonally, Thelma’s rich, almost viola-like

sound making an excellent foil for her brother’s cello. Their

interplay is unselfish, each receding into the background when

the other has the melodic interest. This is a most enjoyable

performance that was the surprise package of the disc. The recording

is highly successful, achieving a vivid sound picture without

any feeling of artificiality.

Maria Kliegel’s 1994 recording of the Sonata for solo cello

and the Sonata for cello and piano easily surmounts the technical

demands of these works, and her playing is, as always, clean

and direct. She is well partnered in the Sonata for cello and

piano op. 4, and Kodaly’s arrangement of three chorale preludes

by Bach, by Jeno Jandó. The rather dull-sounding recording,

however, lets the performances down somewhat.

Guy Aron

|

|