|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

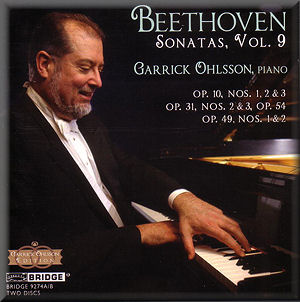

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Piano Sonata No. 5 in C minor, Op. 10, No. 1 (1798) [19:29]

Piano Sonata No. 6 in F major, Op. 10, No. 2 (1798) [11:54]

Piano Sonata No. 7 in D major, Op. 10, No. 3 (1798) [24:24]

Piano Sonata No. 17 in D minor, Op. 31, No. 2 (1802) [24:12]

Piano Sonata No. 18 in E flat major, Op. 31, No. 3 (1802) [20:47]

Piano Sonata No. 19 in G minor, Op. 49, No. 1 (1795/98) [9:09]

Piano Sonata No. 20 in G major, Op. 49, No. 2 (1798/98) [8:54]

Piano Sonata No. 22 in F major, Op. 54 (1804) [13:05]

Garrick Ohlsson (piano)

Garrick Ohlsson (piano)

rec. Performing Arts Centre, State University of New York, Purchase,

N.Y., (dates not given)

BRIDGE 9274A/B [2 CDs 69:16 + 68:21]

BRIDGE 9274A/B [2 CDs 69:16 + 68:21]

|

|

|

This is a particularly well produced issue, with a long, informative

and very readable note, in English only, by Malcolm MacDonald.

The recording is rich, lifelike and very satisfying. We are

not told when it took place, but the two instruments used are

specified, and even listeners less attuned to this kind of thing

will be able to hear the difference between them. It is the

ninth and final volume in American pianist Garrick Ohlsson’s

complete Beethoven Piano Sonata series, and hearing it makes

me keen to encounter the others.

The first movement of the Sonata No. 5 is essentially

the juxtaposition of a harsh rhythmic figure with a tender,

cantabile one, and Ohlsson brings out the contrast between

the two elements most successfully, never letting us forget

how many times the composer marks fortissimo and sforzando

into the score. The calm meditation that is the slow movement

is beautifully rendered, with particularly clear textures in

the rich passages near the end, and sensitively adding a lower

octave in places where Beethoven’s piano would not have had

one. The finale is perhaps not really a Prestissimo,

but at a slightly steadier tempo than some of his rivals Ohlsson

brings out the humour more successfully in this movement, where,

though the notes are clearly by Beethoven, the spirit is close

to that of Haydn.

Humour there is in plenty in the following sonata, and Ohlsson

brings it out in masterful style. Textures are exceptionally

clear – listen to the comical right hand trills in the bass

in the first movement – and Ohlsson is perfectly in tune with

a music toying with Romanticism. One notes how punctilious he

is in respect of the composer’s markings, as if he has examined

and weighed up the effect of every one. In both the first and

last movements he respects the repeat marks in respect of the

exposition, but not the second part. One can only conjecture

as to the reason for this. It really is a little sonata, and

perhaps he felt that the repeats risk making it a bigger piece

than it really is. Schnabel does the same, but that was another

time. I tend to be of a like mind with Tovey, who wrote “…Beethoven

never wrote a repeat mark without thought of its effect at the

moment when the repetition begins…” though he goes on “…though

he may forget the effect of the total length, or may disagree

with our opinion on that point.”

Refreshingly clear finger work characterises the opening of

the third sonata of the Op. 10 group, and all the virtues of

Ohlsson’s playing as indicated above are to be found in this

performance too. The sonata is a strange one, with a long, brooding

slow movement, a gentle minuet and playful trio followed by

a kind of stuttering finale than never seems to get going and

yet teeters on the brink of something profound and serious in

the final bars.

The Classical sensibility is still very much present in the

Sonata No. 17, and Garrick Ohlssohn’s performance of

it is a triumph. Once again his careful attention to the composer’s

markings is evident, skilfully managing a crescendo followed

by piano in the last bar of the slow movement, for example,

and bringing out with impeccable poise the unpredictable accents

in the troubled, constantly moving finale. The opening of the

sonata, a slowly spread arpeggio, is wonderfully pensive here,

contrasting beautifully with the nervous music that follows.

And when, later in the movement, this arpeggio reappears and

is extended by way of a recitative into something at once important

and mysterious, this listener was held spellbound. Wisely, the

spurious nickname “Tempest” occurs only as a reference in the

booklet notes.

The third sonata of the Op. 31 set, in E flat major, is a strange

one indeed. Amongst the most consistently cheerful of Beethoven’s

sonatas, its layout is nonetheless most unusual. There is no

slow movement, but in its place, coming second in the overall

scheme, a movement headed “Scherzo”, but which does not follow

the usual Scherzo pattern. The third movement is headed “Minuet”,

but with a calm, singing quality that makes it feel more like

the slow movement the sonata lacks. Listen how Ohlsson’s left

hand drives the rhythm in the “hunting” finale, and most of

all, the exquisite timing of the very opening of the sonata,

before the main tempo is established in the seventeenth bar.

The two Op. 49 sonatas are appropriately placed at the end of

the second disc, which is also the final disc in the whole series.

Composed earlier than their opus number would suggest, and published

apparently thanks to Beethoven’s brother and without the composer’s

consent, they appeared as “Easy Sonatas” and may have been intended

as teaching works. They contain some delightful passages, but

on the whole are small scale, both in musical ambition and technical

demands. Ohlssen lavishes on them as much care as he does on

the more important works, bringing perhaps rather more weight

to the G minor sonata than we are used to.

The latest sonata in this collection is No. 22 from 1804. It

is one of the lesser known sonatas, falling as it does between

the Waldstein and the Appassionata. Tovey refers

to this “subtle and deeply humorous work”, and Guy Sacre, writing

in French in his book La Musique de Piano (Laffont, 1998)

refers to its “strange originality” and qualifies it as “a caprice

of the imagination.” Strange is certainly is. The first of the

two movements is marked to be played “In tempo d’un Menuetto”,

but it has nothing of the minuet about it, at least once you

get past the curiously short-winded first theme. The finale

is extraordinary, a constant stream of semiquavers from beginning

to end, undisturbed except for the occasional hiccup – or “hiccough”:

Tovey again – listen out for it, there really doesn’t seem to

be a more appropriate word. At the end of the final page, at

a faster tempo, the music just stops. The work reinforces the

idea, too frequently forgotten, of Beethoven as one of the funniest

of composers, and encourages us to rejoice, bearing in mind

the preceding and following sonatas, at the incalculable diversity

of the mind of a genius. Garrick Ohlsson’s performance is fully

worthy of this remarkable work, and the two discs form a most

desirable and satisfying package.

William Hedley

|

|