|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

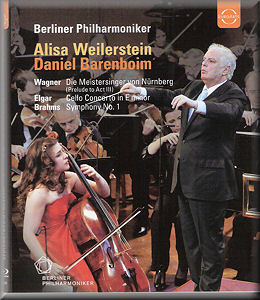

Richard WAGNER (1813-1883)

Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg: Prelude to Act 3 (1868) [8:17]

Edward ELGAR (1857-1934)

Cello Concerto in E minor, op. 85 (1919) [31:04]

Johannes BRAHMS (1833-1897)

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 (1876) [47:27]

Alisa Weilerstein (cello)

Alisa Weilerstein (cello)

Berliner Philharmoniker/Daniel Barenboim

rec. live, Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, 30 April-1 May 2010, DDD

Video director: Rhodri Huw

Sound PCM 2.0 DTS Master Audio Surround Sound

TV format 1080i Full HD 16:9. Region Code All (worldwide)

EUROARTS 2058064

EUROARTS 2058064  [89:00]

[89:00]

|

|

|

The Prelude to Act 3 of The Mastersingers gets a restrained

but sonorous opening. The cellos are joined in seamless progression

by the dignified violas, second violins then first violins.

This is all solemnly meditative before a dawn glow from the

wind instruments. The effect is one of sheer density rather

than brightness. Yet what is enchanting is the softest of sensitive

entries by the strings again from 3:44 (in the DVD’s continuous

timing). Then at 4:46 the video director rightly homes in on

the flutes as they confirm a brighter phase. This is made more

memorable by the ethereal serenity of the probing first violins

in their high register. The brass response to this is suitably

fulsome but Barenboim pares down optimistic motif on its appearance

on strings and clarinet at 7:21; it is, after all, marked p

dolce. Then the lovely oboe take-up appears and also attracts

the video director’s focus. This all helps establish a contemplative

yet beneficent opening mood.

In the Elgar Cello Concerto the tone is set not by the rhetorical

opening solo but by the lyricism of Alisa Weilerstein’s second

solo leading into her introduction of the opening theme. This

has a sad beauty yet flows ever smoothly like a cloudy morning

the features of which gradually clear. The central section (13:09)

is more tender and emotive, especially its second theme (13:48)

featuring lovely calm interplay between strings and woodwind.

The return of the uneasy opening of this section and the soloist’s

lead-in to the reappearance of the movement’s first theme is

passionate yet more rhetorical than angry. I compared Barenboim’s

live performance with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Jacqueline

Du Pré in 1970 (Sony 82876 78737 2). From the opening solos

this is more gritty, tense and reflective. The first theme is

not as smooth, more wan, but the central section has less by

way of contrast. Weilerstein/Barenboim go for an overall smoothness

of line. Du Pré/Barenboim point more clearly the distinction

in phrasing between first and last appearances of the first

theme. You can hear this in particular when the phrasing in

six notes gives way to phrasing in four notes then two notes,

giving a more halting and harrowing effect.

The introduction to Weilerstein/Barenboim’s second movement

scherzo is nifty yet quite warm. It is as if the soloist wants

to get away from the nimble semiquavers into something more

contemplative. Then, just as whimsically, she returns to athleticism.

This is deftly done, all the more so for not parading its virtuosity.

Barenboim supplies by turns a suitably feathery or rosy orchestral

backcloth. Soloist and conductor reveal the joie de vivre.

The ardent second theme (19:41), by not being too soulful, can

live peaceably with this. The 1970 Du Pré/Barenboim scherzo

is has a more substantial, wrenching introduction, a main body

of more nervous energy and a second theme whose declamatory

qualities are emphasised by forceful pointing of rhythm and

accents. The 2010 team give us some welcome respite.

Weilerstein’s slow movement is lyrical, tender and intimate.

The phrasing is sensitive, so are the dynamic contrasts. You

can hear this in the small swell from 24:13 and then the pianissimo

at 24:17, though the pp at 25:40 is undercooked. There’s

lots of portamento but it’s smoothly applied and the

orchestral strings match it when echoing the soloist. This movement

isn’t searing; the appassionato passage (25:00) is no

more than firm. This is where Du Pré is more gripping, lacking

Weilerstein’s beauty but intensely drawn out; arguably overdone.

Again Weilerstein displays a lyrical heart in the expressive

introduction of the finale. Its main theme has a resolute crustiness.

The second theme (29:43) is treated in more musing, exploratory

fashion. The crown of the movement and work is the third theme

(34:09), which can be read as a sad summation of life’s loves

and passing. Weilerstein/Barenboim play it with feeling and

dignity, keeping it flowing until Weilerstein finds her greatest

expressiveness for the return of the slow movement theme and

a magical shading down to pianissimo (37:42). Du Pré

is weightier for the opening crustiness and engages your attention

more. Her climax of the third theme is heartrending but her

return to the slow movement theme is over-expansive.

Tension is ever-present in Barenboim’s first movement of Brahms’

First Symphony. It underpins a powerful introduction with strings

that can sing. He also lays bare an epic quality as can also

be heard in the later oboe, flute and cello solos. A relative

formality is brought to the first theme but a greater opulence

can be found in the second one (45:09). A pity there’s no exposition

repeat. It’s also a shame that the lady double-bassoon player

isn’t pictured in her crucial solo. Instead at 48:59 at the

beginning of the crescendo in the development towards

the recapitulation we see the doubling cellos. For the next

minute or so that turbulent crescendo is thrillingly

realized. In the coda the sighing strings are allowed to be

a touch more velvety.

The tension is still there at the beginning of the slow movement

with intense, heavy string sound permitting a more striking

contrast when oboe and flute offer a balmy escape. Further relief

comes in the lovely, seamless singing line of the solos from

oboe and clarinet. There remains a steely quality to the strings

whose statements of comfort still have a careworn perspective.

They become more lilting towards the closing section with its

sweet violin solo and smooth doubling horn judiciously balanced

before a finely sustained violin solo ending. The third movement

intermezzo is wonderfully assured. At its outer edges Barenboim

secures a lovely clarity of line: all is smooth, light and comely.

The second section (65:45) is more urgent, the trio (66:22)

more sombre and portentous before a benevolently pastoral close.

On DVD you can see how controlled by Barenboim this is but it

sounds quite free.

The finale has a caring, expressive opening followed by neat

contrasting of capricious pizzicato and grave arco

strings before an edgily passionate horn solo. The big

string tune is rich-grained and flowing, yet this is a movement

of many contrasts. It’s all nicely detailed by Barenboim with

flexibility of tempo and dynamic but never allowed to halt the

overall burning progression. Two examples that made Barenboim

himself smile in appreciation: the touches of portamento

from sunny, Viennese style violins from 83:18 and the Mendelssohnian

texture of soft tremolando strings against ascending

then descending wind from 84:54.

Here then are interpretations of considerable substance in a

Blu-Ray Disc which has superb crispness of picture and clarity

of sound.

Michael Greenhalgh

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews