|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

|

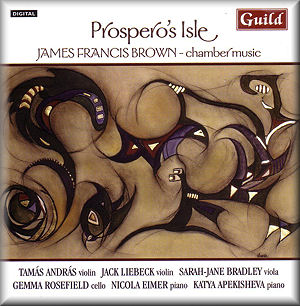

Prospero’s Isle

James Francis BROWN

(b. 1969)

Piano Quartet (2004) [17:03] (a)

Violin Sonata (2001, rev. 2003) [20:13] (b)

Prospero’s Isle (2006, rev. 2007) [14:32] (c)

String Trio (1996) [22:40] (d)

Tamás András (violin) (a); Sarah-Jane Bradley (viola) (a, d); Gemma

Rosefield (cello) (a, c, d); Katya Apekisheva (piano) (a, b); Jack

Liebeck (violin) (b, d); Nicola Eimer (piano) (c)

Tamás András (violin) (a); Sarah-Jane Bradley (viola) (a, d); Gemma

Rosefield (cello) (a, c, d); Katya Apekisheva (piano) (a, b); Jack

Liebeck (violin) (b, d); Nicola Eimer (piano) (c)

rec. 27-28 July 2008, Concert Hall, Wyastone Leys, Gwent, UK (a,

b, c) and 17-18 November 2008, Henry Wood Hall, London (d). DDD

GUILD GMCD7354 [74:30]

GUILD GMCD7354 [74:30]

|

|

|

Alan Mills, writing in the booklet, suggests that James Francis

Brown’s work “will possibly remind some listeners of a certain

type of mainstream English music in the 20th century – and composers

such as Vaughan Williams, Ireland or even Finzi.” His essay

also makes much of the fact that today’s composers are no longer

afraid of writing tonal music. That said, and accepted, anyone

expecting this composer’s music to sound like one of those evoked

above is, I think, in for a surprise.

The earliest music on the disc is the String Trio from

1996. The composer evokes Beethoven in connection with this

work, which features a short Beethoven quotation. Beethoven

certainly comes to mind when one hears the strongly rhythmic

opening theme played over constant, rushing semiquavers. Much

of this first movement continues in this vigorous vein, though

the second theme is calm and returns at the close. The second

movement is a set of six variations, opening in sunny mood before

clouds gather. The final variation returns to the mood of the

opening. It is the shortest of the six, perhaps just too short

to be as adequate a summing up as the composer probably intended.

The work is nonetheless expertly written for the medium, with

no dryness of texture, and the listener is eager to return to

it.

The three-movement Violin Sonata begins with a dramatic

and highly chromatic opening gesture from both instruments,

leading to a series of contrasted episodes. The music, often

beguilingly melodious, sometimes comes to a halt which one could

take as the end of the movement, but then sets off again on

another tack. The Presto requires virtuoso playing from both

instrumentalists, and its central section, with repeated quavers

in the violin part is strikingly lovely. The finale is one long

song, restlessly moving towards what is, undoubtedly, a kind

of resolution, the very end of the work being undeniably effective.

The composer’s notes, however, tell us that the work was originally

three separate pieces that became “increasingly related to each

other” during composition. Striking, brilliantly written and

often very beautiful though the music is, I think it shows.

The Piano Quartet opens with huge energy amid much hammering

and sawing, expressions I use descriptively and with no pejorative

intent. The second subject is in total contrast, and made me

think of Tippett. Then there is a certain “busyness” to much

of the music that might put the listener in mind of Hindemith.

The musical language is skilfully employed throughout, often

highly chromatic, yet moments of repose – and, in this case,

the whole work – coming to rest on a simple major chord do not

seem incongruous. The composer analyses the work, which is in

a single movement, as a sonata form structure with an extended

coda. One can hear the two “subjects” plainly enough, but there

is much less sense of a development section, and very little

feeling of arrival for the recapitulation, which in any event

the composer says is “substantially reorganised and re-interpreted.”

The musical ideas are striking and often beautiful, but I don’t

always feel I know where I am in the piece, nor where the music

is taking me. Nor do I think the rather splashy coda quite comes

off, but all credit to Brown for not being afraid of writing

a decisive close.

Of Prospero’s Isle, for cello and piano, the composer

writes “…it was not exclusively the magical aspects of the play

that attracted me, for The Tempest is also a study of

power and mastery over people, events, even the very elements

of nature. It is tempting as a composer to see parallels with

the organisation and control over the elusive substance of music.”

I confess to being somewhat allergic to this kind of stuff,

as I also am to “Perhaps the characters of Prospero and Miranda

are alluded to…” Either they are or they aren’t, and he should

know. Having got that off my chest, let me turn to the music,

which is no less impressive than that of the other three pieces.

This work is the most tonal of the four, especially so at the

outset where the composer profits from the rich sound of parallel

sixths when played by a cello. The music is highly melodic,

even in the more dramatic passages, and in spite of what the

composer writes, is full of magical and beautiful sounds, mostly

guaranteed to “give delight and hurt not”. At around the eight

minute mark there is a forceful passage leading to an ardent

melody for the cello accompanied by downward spread arpeggio

chords on the piano; in such passages I tend to wish Brown would

put less in, especially in the piano part which threatens to

overwhelm the cello.

The booklet contains detailed information about each of the

young players, and rightly so, as the performances are of remarkable

virtuosity and conviction. They are clearly captivated by the

music. Listeners will be too, for is spite of any slight reservations

I might have, this collection of chamber pieces shows a composer

of the utmost integrity, totally in command of the medium, with

a voice of his own and an aural imagination to match. The disc

is beautifully recorded and I recommend it warmly to any collector

interested in the bewilderingly diverse world of contemporary

music.

William Hedley

|

|