|

|

|

availability

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

|

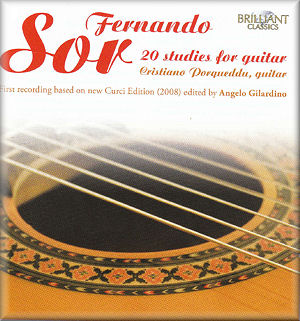

Fernando SOR (1778–1839)

20 Studies for Guitar (Edition Curci (2008) by Angelo Gilardino)

No. 1, C Major [2:29]; No. 2, C Major [0:54]; No. 3, A Major [1:21]; No. 4, D Major [1:23]; No. 5, B Minor [2:55]; No. 6, D Major [1:45]; No. 7, F Major [2:05]; No. 8, D Minor [2:18]; No. 9, A Minor[ 1:04]; No. 10, A Major [ 1:44]; No. 11, E Major [1:37]; No. 12, A Major [1:46]; No. 13, D Minor [3:14]; No. 14 A Major [6:17]; No. 15, D Minor [1:45]; No. 16, G Major [2:24]; No. 17 E Minor [3:44]; No. 18, E-Flat major [4:42]; No. 19, B-Flat Major [4:46]; No. 20, C Major [3:45]

Cristiano Porqueddu (guitar) Cristiano Porqueddu (guitar)

rec. Nuoro, Italy 10-21 November 2009

BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9205 [52:08] BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9205 [52:08]

|

|

|

In 1945, Andrés Segovia wrote the preface to the most famous of all musical editions for the classical guitar: his recension of Twenty Studies by Fernando Sor. Selected by Segovia from the significant number that Sor wrote, they represent both didactic and musical masterpieces. Segovia described them as ‘containing arpeggios, chords, repeated notes, legatos, thirds, sixths, melodies in the higher registers, and in the bass, interwoven polyphonic structures, stretching exercises for fingers for the left hand, for prolonged holding of the cejilla, and many other formulas.’ Students who assiduously practice these studies, and master them, are considered well on the way to total mastery of the instrument.

Despite their popularity and place in guitar pedagogy, few recordings of the complete set have been made. Surprisingly, Andrés Segovia never recorded them all on one disc. According to the liner-notes, Segovia recorded a total of thirteen on several different occasions. The suggestion is also made that not all of Segovia’s recordings may have yet been discovered. Probably the most famous recording of the set is that by John Williams made in the 1963 (Westminster XWN 19039) and again released several more times, including in 1967 (EMI CLP 1702). Now long out-of-print, it appears this recording has never been reissued on CD, however most of it has been uploaded to the YouTube site. Around the same time the Spanish player José Luis González, then domiciled in Australia, made a recording of the complete set for CBS Australia (BR 235128). Considerably later American, David Tanenbaum recorded the 20 Studies along with studies by Carcassi, and Brouwer (GPS 1000CD). Probably others also recorded the complete set, but these have not been readily accessible.

In more recent times there has been much scholarly focus on ’historically informed practice’ and preoccupation with the exact and precise intentions of composers, guitar music not excepted. Editions of the Sor Studies paying strict attention to these aspects include those of Chanterelle, and Tecla. The review disc presents the famous Twenty Studies by Sor, as originally selected by Segovia, under the umbrella of a different edition: that of guitarist/composer Angelo Gilardino and published by Curci (2008). One may safely assume that in preparing a new edition, Gilardino felt that there were deficiencies in the existing ones.

Segovia was not alone in making changes when editing music. Performing musicians including Bauer, Schnabel, and Paderewski produced interpretive editions. However Segovia was at a distinct disadvantage in preparing the Sor Twenty Studies edition: it is highly unlikely that he had access to original material, but instead to editions of the same material by Napoleon Coste, himself a student of Fernando Sor. We may conjecture that these studies by Sor, essentially a Classical composer, came to the twentieth century guitarist through the dual filter of two Romantic guitarists: Segovia and Coste. Segovia may have been taken less to task by those composers whose work he edited, in the knowledge that even his own work was subject to change. His recording of Estudio sin Luz omits four measures from the published score.

The discussion regarding score sourcing, historically informed practice, and original versus modern instruments can become controversial. One essential question is whether editors have licence to change, in any way, the original intentions of the composer, if indeed those intentions can be ascertained and verified? The liner-notes by Gilardino indicate that in creating his edition he used those scores published at the time, and therefore under the control of Sor (?). He comments: ‘essentially we arrived at a sort of urtext, created through meticulous comparisons of the different scores.’

This review is not intended as a treatise on the merits of urtext and facsimile or justification for interpretive editions. It can however be said with conviction that many of Segovia’s changes – not only to the Sor Studies - sound good musical judgement to the ear. An example is his change to the harmony in the third last measure of Study No.6. Purists however revert to what is claimed authentic (but sounds inferior).

Insensitive to the pursuits of academics, José Luis González could be considered the Grand Poohbah of iconoclasts. In Study No. 18 he eliminated the rather repetitive seven measures from the second section and also included several others of his own composition based on the previous section’s theme.

Many would contend that the result was a superior sounding piece of music, and more inspiring to play, but would Sor approve? González had the courage of his convictions to record it exactly as he edited it in his subsequent recording of the Twenty Studies. This was around the same time Williams produced his recording of the same works; direct comparisons and criticisms were inevitable.

After playing the Bagatelles to Sir William Walton, Bream commented: ‘I played it exactly as you wrote it.’ Walton responded: ‘No, you got it better.’ Clearly the composer may not always feel that his intentions are sacrosanct.

To comment extensively on the renditions found on the review disc one would need to compare the scores of all aforementioned editions which is beyond the scope of this review. Some differences between Segovia’s edition and the Curci are immediately evident. Conspicuous examples include the repeats that Segovia eliminated in several studies; also the embellishments in Study No. 1 that are changed, and the aforementioned change to No. 6.

Cristiano Porqueddu was born in Nuoro, Italy and initially taught the guitar by his father. Having obtained his diploma at the conservatorium of music he attended different Masters and specialist courses all over Europe, studying interpretation of Baroque music and eighteenth and nineteenth music in depth. He is the winner of numerous awards and international competitions.

While one may debate the validity of the various editions of the Sor Twenty Studies, including the latest utilized on this disc, less open to debate is the excellent playing by Porqueddu. His technique is meticulous and he pays attention to every note and dynamic of the music. The playing is not without personal idiosyncrasy and considering the environment, this is rather endearing. Given the slavish preoccupation with editions, one may anticipate further alliance through the use of an original instrument of the day. Porqueddu uses a modern instrument, unidentified but nonetheless most agreeable in general sound.

Liner-notes by Angelo Gilardino are usually informative and helpful, but unfortunately not always accurate. The review disc details of content are incorrect: they are obviously taken from another Cristiano Porquedda recording, Transcendentia. Since some repeats have been changed, no comparative conclusions on tempi can necessarily be drawn from timings.

Zane Turner

|

|