|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

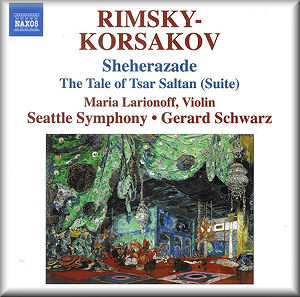

Nikolai RIMSKY-KORSAKOV

(1844-1908)

Scheherazade, Op 35 [45:51]

Tale of Tsar Saltan, Suite, Op 57 [19:15]

Tale of Tsar Saltan, Flight of the Bumblebee [1:31]

Maria Larionoff (violin) (Scheherazade)

Maria Larionoff (violin) (Scheherazade)

Seattle Symphony Orchestra/Gerard Schwarz

rec. 7 May 2010 (Scheherazade), 4 June 2010 (Tsar Saltan), 16 June

2010 (Bumblebee), Benaroya Hall, Seattle, Washington, USA

NAXOS 8.572693 [66:37]

NAXOS 8.572693 [66:37]

|

|

|

I put this disc on expecting decent playing, an acceptable artistic

vision, and little more. Was it prejudice? Perhaps it was the

fact that recent Naxos efforts in the core repertoire have been

so hit-or-miss: Pietari Inkinen’s sometimes-dreary new Sibelius

cycle, Jun Märkl’s bland Daphnis et Chloé, the LSO’s

similarly bland Brahms and Bartók coupling. Perhaps it was that

the Seattle Symphony Orchestra and conductor Gerard Schwarz

have previously teamed up (on Naxos and Delos) to provide us

with the byways of obscure American (and especially Jewish-American)

music: Achron, Bernstein, Diamond, Foss, Hovhaness, Schoenfield,

Schuman. Perhaps it was the fact that Scheherazade is

easy to play well, but hard to play memorably. So I’ll

confess: I had low expectations.

They were blown away. This is spectacular, an effort in which

everyone has put their best foot forward. Gerard Schwarz leads

with an unerring sense of when to be expansive, when to indulge

in romantic gestures, and when to step on the gas pedal and

let the music explode with passion. The Seattle Symphony sounds

world-class, with great woodwind soloists (especially the oboist),

punchy brass, and a satisfying blend of precision and expression.

The recorded engineers have hampered solo violinist Maria Larionoff

with too much reverb, but they have also captured the proceedings

in a full orchestral sound which starts with crackling tuba

and satisfyingly present double basses and builds upward in

a richly layered sound-picture. At times the orchestra sounds

uncannily like an organ.

This Scheherazade is very nearly beyond praise; aside

from the reverb which surrounds the violinist (but nobody else,

oddly, except briefly the solo clarinet in the second movement),

everything goes right. The opening movement’s seascape builds

with slow, steady fervor until the climaxes reach feverish degrees

of intensity. The “Kalender Prince” contrasts the lush wind

solos with fierce, violent outbursts: when the central section

opens, watch out. The percussionists are precisely on-rhythm

and boldly project their parts. The love-scene slow movement

isn’t as lavish or sensual as it could be, but it flows naturally

and benefits from those superb wind soloists. (It can’t be mentioned

often enough that oboist Ben Hausmann makes his every solo unforgettably

tender.) And the finale, enlivened with a rumbling bass drum,

starts with an atmospheric festival and concludes with Maria

Larionoff’s most heartfelt solo work of all.

Mostly, it’s thrilling just to hear a performance this good

in sound this good. Probably there are a dozen orchestras which

have played this well in this music in past decades (though,

to my mind, approaches like Ansermet’s are too fast and Haitink’s

too colorless), but Naxos’ crystal-clear sound quality takes

things to a new level. How satisfying it is to hear the tubas

lending oomph to the opening outburst of the finale! How delightful

it is to really feel the bass drum, or to hear the harp

serenades like something from a dream!

Tale of Tsar Saltan is at least as good. The first movement

(Tsar’s Farewell and Departure) has a snappy directness, Schwarz’

perfectly-chosen tempos matched every step of the way by the

Seattle players’ gung-ho commitment. The moodier central movement

(The Tsarina in a Barrel at Sea) is suitably emotive: the violins

shriek in psychological agony, the pizzicato chords are like

daggers, the seascapes shimmer with dark splendor and at times

sound like far more “modern” composers’ work, and the droning

bass again shade in the background with the richness of an organ.

The finale (The Three Wonders), light on its toes and enjoyably

skittish, bounces off the walls with energy, and in the second

minute, as the bass drum rolls start piling up on top of brass

fanfares, motoric string rhythms, and wind players running for

cover, it’s hard to resist standing up or drawing a sweat.

There are a hundred other recordings of this music, but once

a certain level of artistic brilliance is reached, comparisons

become moot. My favorite Scheherazade is still Evgeny

Svetlanov’s sprawling, voluptuously romantic account with the

LSO, a live take on BBC Legends. At fifty minutes it overflows

with erotic warmth. One place in which it is noticeably superior

is in the flute-harp duet at the end of “Kalender Prince,” which

Schwarz takes largely in tempo but for which Svetlanov stops

time and indulges in a breathtaking, slow caress of the soloists.

But this new Seattle/Schwarz account takes second place easily,

brushing aside such luminaries on my shelf as Haitink, Bátiz,

and Ansermet - whose Tsar Saltan lacks vividness compared

to this - with its irresistible combination of sense of occasion,

(mostly) opulent sound, and intelligent direction. It is just

as satisfying as Eugene Ormandy’s glorious Philadelphia reading,

and in modern sound to boot. The only real flaw is that the

disc ends with Flight of the Bumblebee. Was that necessary?

Not only is it a trifle we’ve all heard a million times, it’s

an anticlimax. Every single track on the CD has more emotional

weight, more dramatic oomph, and a more compelling ending. After

sitting through the bumblebee’s short flight, I doubled back

and listened to Tale of Tsar Saltan a second time for

a more satisfying conclusion. Not that I minded terribly.

So in a way, this disc has restored my faith. After the drudgery

of Märkl’s Ravel, or the lack of distinction of Charles Dutoit’s

Scheherazade CD with the Royal Philharmonic only a few

months ago, it becomes all too easy to wonder what, exactly,

the purpose is of continuing to issue recordings of works which

have been released hundreds of times. Any new disc of beloved

music needs to offer something that cannot be had on any old

disc of that music. And, thankfully, this Scheherazade

has just that.

And, while I’m on my soap box, I want to add something else.

The standards of classical artistry these days are phenomenally

high, so high we need to step back for a second and gain some

perspective. Sixty years ago, to draw this kind of impassioned

but precise response from an orchestra, any orchestra, you needed

to be a Thomas Beecham or a Eugene Ormandy. Moreover, you needed

to have one of the world’s best orchestras at your disposal,

with strong personalities in every department, soloists who

could rise to the challenges, and the energy to thrive when

asked to throw all inhibitions to the wind. Today, we have a

Scheherazade by a seemingly average American orchestra

based in a city smaller than Leeds, Valencia or even El Paso,

Texas, led by a conductor associated with ‘specialist’ repertoire,

produced for a budget-priced record label — and the results

are nothing short of spectacular.

Brian Reinhart

|

|