|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads |

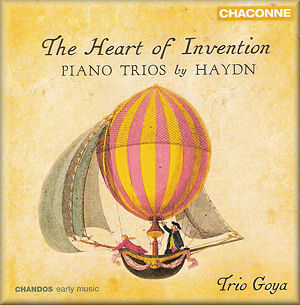

Franz Joseph HAYDN (1732-1809)

The heart of invention

Piano Trio no. 25 in C major, op. 75 no. 1 (Hob.XV:27) (1797) [18:52]

Piano Trio no. 26 in E major, op. 75 no. 2 (Hob.XV:28) (1797) [16:13]

Piano Trio no. 24 in F sharp minor, op. 73 no. 3 (Hob.XV:26) (1795)

[14:49]

Piano Trio no. 22 in D major, op. 73 no. 1 (Hob.XV:24) (1795) [14:13]

Trio Goya

Trio Goya

rec. Real World Studios, Box, Wiltshire, 7-10 December 2008, DDD

CHANDOS CHACONNE CHAN 0771 [64:33]

CHANDOS CHACONNE CHAN 0771 [64:33]

|

|

|

Confidence and exhilaration are the chief impressions left at

the opening of this CD which begins with Haydn’s Piano Trio

25. Brightness and clarity of sound in a close recording contribute

to this as does the tight chamber ensemble. The period instruments

are well matched in rhythmic impetus. The fortepiano is the

distinctive difference in comparison with modern instrument

recordings using a pianoforte. Where the pianoforte gives you

vibrant creamy colours the fortepiano offers more pastel shades,

reduced sheer power in tone but still percussive impact where

appropriate. Admittedly it’s an acquired taste: what I find

pleasing delicacy others may feel is quaintly puny. What’s not

in doubt in Trio 25 from the first movement is the work’s virtuosity:

the lively times when violin and piano exchange scampering in

semiquavers, the rakish lolloping arpeggios in the piano’s left

hand at tr. 1 1:06 and in the right hand at 2:00. Then there’s

the attractive variation in this performance when the violin

decorates the pause at the end of the first statement (0:27)

but the fortepiano decorates it in the repeat (2:44), a typical

example of Trio Goya’s refinement.

I compared the classic 1972 recording on modern instruments

by the Beaux Arts Trio (Philips 454 098-2). Timing at 6:59 against

Trio Goya’s 8:41, the BAT deliver a truer Allegro. This

makes the piece more light-hearted, the piano’s semiquavers

especially frothy and arpeggios more skittish. Their emphasis

on horizontal flow shows well how the conversation mainly between

piano and violin knits together. Trio Goya, on the other hand,

give more attention to the vertical texture, thus placing the

entries and effects between the instruments more deliberately.

This imparts more of a serious and sometimes heroic vein to

the whole with a more troubled development (4:35). There’s a

gain in clarity if a little loss in spontaneity.

In the siciliano slow movement, however, it’s TG who

provide a truer Andante which very attractively celebrates

the simple, song-like flow of the melody and engagement by all

three instruments. This is enhanced by the piano delicately

elaborating the significant staging posts. BAT are more expansive

and full of romantic nuance and reflection. They are more arty

but this makes the central section in A minor somewhat heavy

where TG are purposeful. In the Presto finale it’s BAT

who are a touch niftier at 4:37 against TG’s 5:06. Nevertheless

TG’s account is vivacious and emphasises the incisive rhythms.

The development (2:35) is full of determination. There’s a particularly

relished heady moment from 4:24 just before the coda when all

three instruments have the running semiquavers which are the

piano’s staple diet in this irrepressible piece. BAT are more

nonchalant at the start, with lighter articulation, but find

more dynamic shading generally and more contrast and drama in

the development.

In the three other trios on their CD I’ll concentrate on the

virtues of Trio Goya’s period instrument performances. Piano

Trio 26 begins with a homely melody. It’s rendered more integral

by its theme being presented at the same time as a sustained

song in the right hand of the piano and a pizzicato articulation

in the violin. The piano bass is staccato, doubled by

a pizzicato cello. But it’s the violin’s soaring escape

from this, an airy expansion of its potential, which proves

to be in TG’s account the most welcome feature. The central

movement is even more of a surprise, a sequence of variations

on a baroque style bass line, the first of which (tr. 5 0:21)

manages at the same time to be a reflective and soulful piano

solo (Maggie Cole). Violinist Kati Debretzeni makes her impact,

however, in the third variation in which she takes up the ‘bass’

in upper register (2:52) against the theme in the cello. One

feels for cellist Sebastian Comberti, urbane in tone and expression

though he is throughout, in drawing comparatively the short

straw most of the time. The finale seems an informal affair

with dancing theme and offbeat kicks but the development (tr.

6 1:42) has an element of grimness in its purpose and the violin’s

closing high register sweetness contains bittersweet echoes.

This is indeed mature music.

Piano Trio 24 has a first movement exposition whose opening

clouds begin to be dispelled even by the second part of the

first theme (tr. 7 0:19). The second theme (0:48) sparkles with

the piano’s semiquaver descents and its second part (1:04) is

positively jolly. However, the clouds are delineated further

in the development (2:55) which finds even that jolly theme

reappearing in thoughtful guise. TG’s performance is crisply

pointed but the second part of this movement from the development

should be repeated to balance the exposition repeat. Except

balance isn’t the right word because that second part without

repeat takes 2:32. Rather it’s a matter of asserting the home

key of F sharp minor and the contrast of F sharp major in the

gorgeous slow movement. You may well recognize this as it’s

another version of Symphony 102’s slow movement, now a semitone

higher. It’s charming, expressive and exquisite, more warm and

personal with the theme shared in turn by piano and violin.

In the lovely shape and phrasing of Trio Goya’s performance

I found myself preferring this Piano Trio version for its fresher,

cleaner projection and clarity of harmony. The Minuet finale

is of a stoic cast, dominated by the piano. As a kind of Trio

a variant of the melody makes the switch once again from F sharp

minor to major (tr. 9, 2:16), with violin now to the fore, to

show that there can be brighter days. These are also briefly

distilled in the coda (4:46).

Lastly Piano Trio 22, the least demonstrative of the four on

this CD but satisfying in its quiet way. Its first movement

has an easygoing, mellow manner owing to the pervasiveness of

its opening six-note motif from which the piano occasionally

escapes in tripping semiquavers beneath a suddenly perky violin.

Its development (tr. 10, 3:54), though not without incident,

is unusually contented. The slow movement, this time dominated

by its opening four-note motif, is more intriguing. For me Trio

Goya catch in it a prototype for a Mahler funeral march because

there’s a playful element distanced from its formal features.

It can hurl itself in high tragic vein into a succession of

demisemiquavers above the tune in the cello and left-hand of

the piano (tr. 12, 1:50). But then the piano’s plangent statement

of the falling motif is waspishly subverted by the violin’s

rising interruptions (2:04). The movement ends with a question,

answered positively by the finale. This is marked ‘Fast but

sweet’, a difficult combination to bring off but TG do it well.

You’re relaxed by its freer, expansive, assured and benign line,

further set in relief by the contrast of a stormy central section.

Here then are discerning accounts which ably show how fine and

still underrated a composer Haydn is. Close to the sound he’d

have expected, they are presented sympathetically without showmanship

yet with sensitive and judiciously varied ornamentation in repeats.

Michael Greenhalgh

|

|