|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

Gaetano DONIZETTI

(1797-1848)

Maria Stuarda - Lyric tragedy in two acts (1834)

Elisabetta, Elisabeth the first of England - Sonia Ganassi (mezzo)

Elisabetta, Elisabeth the first of England - Sonia Ganassi (mezzo)

Maria Stuarda, Mary, Queen of Scots - Fiorenza Cedolins (soprano)

Roberto, Count of Leicester - José Bros (tenor)

Giorgio Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury – Mirco Palazzi (bass-baritone)

Lord Guglielmo Cecil, Lord High Treasurer – Marco Caria (baritone)

Anna, Maria’s companion – Pervin Shakar (soprano)

Orchestra of the Teatro La Fenice/Fabrizo Maria Carminato

Stage direction, set design, costumes and lighting by Denis Krief

rec. live, Teatro La Fenice, Venice, 30 April–3 May 2009

Filmed in High Definition and manufactured from an HD source. Picture

format: NTSC 16:9. Sound format PCM Stereo. DTS-HD MA 5.0

Subtitles: English, German, French, Spanish and Italian

Performed in the Critical Edition by Anders Wiklund

UNITEL/C MAJOR 704304

UNITEL/C MAJOR 704304  [140:00]

[140:00]

|

|

|

There are times when the life of a reviewer becomes increasingly

hair-tearing and frustrating. Nowadays, it’s a matter of live

recordings in video issues of opera. This generally leaves the

recording company at the mercy of pot luck in respect of the

producer and singers involved, These matters relate more to

the artistic policy and budget limitations of the theatre whence

the recording originates. It can be particularly frustrating

when a performance is filmed in high definition, with a good

cast of singers in a beautiful theatre, when the best use of

the video technology involves views of the auditorium or the

environs of the theatre. In this case the environs of Venice’s

lovely rebuilt and restored La Fenice theatre can hardly be

bettered. The views across the Lagoon to St Mark’s Square, the

magnificent Campanile, Doge’s Palace, and Cathedral itself along

with the Grand Canal are stunning (CH.1). The bad news is that

the views of the auditorium are in no way matched by the production,

sets and costumes. These completely waste the possibilities

of the technology as well as seriously limiting the dramatic

impact of the opera concerned.

The House of Tudor, together with the Romantic novels

of the likes of Walter Scott, became increasingly popular among

composers as the basis for opera libretti from the second decade

or so of the premiere ottocento, the first half of the nineteenth

century in Italy. The indirect cause of this involved the city

censors who had to agree the subject of an upcoming opera and

also its stage presentation. Ever tired of the historical subjects

of mythical ancient Greece and the nearer to home wars between

the Guelphs and Ghibellines in pre-Renaissance Florence, the

House of Tudor and the Queen of England had a more romantic

appeal as well as the possibility of colourful productions.

Donizetti wrote a trilogy of bel canto operas based around

the Tudor Queen: Anna Bolena (1830), Maria Stuarda

(1834) and Roberto Devereux (1837). Maria Stuarda

has become the most popular work in that trilogy.

At the time of the composition of Maria Stuarda in 1834

Donizetti had embarked on the richest period of his career.

With the death of Bellini the previous year he was in a pre-eminent

position among the many Italian composers of the day. Of his

previous forty-five or so operas at that date, nearly half had

been composed for Naples. He had returned there early in 1834

with a contract to write one serious opera each year for the

Royal Theatre, the San Carlo, as well as having an invitation

from Rossini to write for the Théâtre Italien in Paris. Things

looked up for him even more when, in June, by command of the

King of Naples, he was appointed professor at the Royal College

of Music in Naples.

The renowned librettist Romani failed to come up with a libretto

for the contracted opera, so Donizetti turned to a young student,

Giuseppe Bardari, who converted Schiller’s play with its imagined

confrontation between the two Queens, one that never happened

in real life. In the opera, the meeting does not go as Leicester

hopes, with Elisabeth chiding Maria beyond the latter’s patience.

In the famous confrontation the Catholic Stuart Queen Maria

breaks and responds to Elisabeth’s chiding and demeaning by

referring to the Protestant English Queen Elisabetta as Impure

daughter of Anne Boleyn (CH.19) with the famous phrase Profanato

e il soglio inglese, vil bastards, dal tuo pie! (The English

throne is profaned, despicable bastard, by your presence!).

During rehearsals this dramatic confrontation between the Queens

caused a physical fight between the singers concerned! News

must have reached the Royal Palace where Queen Christina, wife

of King Ferdinand of Naples, and a descendant of Mary Stuart,

objected. The King acted as censor and banned the new opera.

Donizetti was not in a position to resist when required to set

the music to another text. The subject chosen was related to

the safer one of the strife between the Guelphs and Ghibellines.

With some new music it was presented as Buondelmonte;

it was not a success.

Donizetti withdrew Maria Stuarda after its Naples rehearsals,

determined to have it staged somewhere in the form he had originally

planned. In the interim he composed Gemma di Vergy for

Milan, Marino Faliero for Paris and Lucia di Lamermoor

for Naples. Maria Stuarda finally reached the stage

at La Scala in December 1835 with the headstrong Maria Malibran

determined to sing the original words of the infamous confrontation.

She did so, and Maria Stuarda was yet again withdrawn

after a mere six performances on the instructions of the Milanese

censors. Maria Stuarda did not reach Naples in its original

form until 1865 when both composer and Bourbon rulers were long

gone. After this it disappeared until revived in 1958 in Bergamo,

Donizetti’s hometown. In the 1970s the likes of Joan Sutherland,

Montserrat Caballé, Leyla Gencer and Beverley Sills took up

the title role ensuring its future in opera houses in Italy

and elsewhere.

Although Maria Stuarda lacks the flow of melodic invention

of Lucia di Lammermoor it does not lack in melodic beauty.

Whilst the manuscript of Maria Stuarda is lost several

non-autograph manuscripts exist as do ten pieces from Buondelmonte

and ten from Milan of Maria Stuarda. This performance

of Anders Wiklund’s Critical Edition, is given in two

acts. In this version the original act two, the Fotheringay

Act, follows on directly from the conclusion of the act

one duet between Elisabeth and Leicester (CH. 7) with the former

pleading Maria’s case with the woman infatuated by him. The

tempestuous meeting between the Queens is given here as No.

6, the act one finale (Chs 17-20). The original act three is

given as the second act (CHs. 21-34).

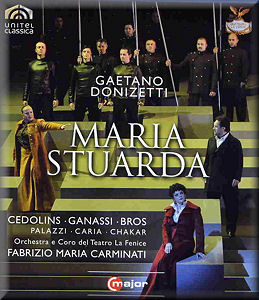

I have already given some indication of my views of the production,

sets and costumes as well as the musical performance. The appended

picture shows the nature of the costumes, of some indeterminate

period, but it’s certainly not Tudor. Maria later defies history

by being dressed haute couture with a white strapless

gown and stole, the latter dispensed with as she walks the steps

to the scaffold, I suppose it would make her neck more accessible

for the axe-man! Elisabetta lacks any touch of the regal in

her costume, her stark demeanour with tightly drawn-back hair

and haughty manner being considered sufficient. All the men

are dressed in black, José Bros as Leicester being less formally

open-necked. The Talbot of Mirco Palazzi seems to be blessed

with a dog collar; although he takes Maria’s confession I am

not aware that he was a man of the cloth in history or in Schiller.

The set is composed wholly of rectangular blocks, mostly of

seat height except some that were raised periodically so that

a character could hide behind them. These blocks were laid both

parallel and at right angles to the stage with the whole seeming

like a maze. The semi-reflective nature of the blocks allowed

for lighting effects such as green to represent the forest at

Fotheringay. As to production, there was little, with what there

was being questionable, such as the physical intimacy, even

fondling (CH.9), between Elisabetta and Leicester in act one.

Given the words of both, this seemed wholly inappropriate.

Thankfully the performance from the orchestra, chorus and soloists

was on an altogether different plane. On the rostrum Fabrizo

Maria Carminato had an obvious feel for the genre, supporting

his singers whilst also moving the drama on and giving weight

and colour, where appropriate, to the more dramatic moments.

Sonia Ganassi, despite lacking any regal adornments, gives a

formidable sung and acted interpretation of the sexually frustrated

Elisabetta. I was not overly impressed by her Eboli in the 2008

Covent Garden Don Carlo (see review)

but here she is wholly at ease vocally with warm expressive

tone added to clear diction and committed acting. If Fiorenza

Cedolins does not match the formidable and vastly experienced

Mariella Devia in the La Scala staging by Pier Luigi Pizzi (see

review),

hers is still a commandingly acted and sung performance. Her

voice has one or two patches where the registers are not ideally

knitted, but as a total interpretation of this demanding role

it is one I would go far to see.

José Bros’s rather white plangent tone is ideally suited to

such bel canto roles as Leicester, but at times he inclines

to push his instrument too far and an intrusive vibrato results

(CH. 33). His somewhat portly demeanour does not help his acted

characterisation. This is not a problem with the implacable

and physically imposing Cecil of Marco Caria, his baritone having

a dry hue from time to time. As the sympathetic Talbot only

his apparent youth spoilt Mirco Palazzi’s interpretation. His

even-toned expressive singing promises a fine future. In the

comprimario role of Anna, Pervin Shakar is firmed of tone and

expressive along with a sympathetic stage presence. I guess

she is a Maria in waiting.

This simplistic set and non-production is shared between Venice’s

La Fenice, the Teatro Verdi in Trieste and Palermo. Given the

division of cost, the theatres might have gone for a producer

who knew a little more and was more sympathetic to what he was

representing. As it is, this would have been better semi-staged

with precious money saved at a time when Italian theatres are

being forced to tighten their belts as previously fairly generous

state subsidies are savagely cut back. In the meantime and despite

the wonderful views of Venice in high definition, stick with

Pizzi’s La Scala or the Sferisterio (see review)

productions.

Robert J Farr

|

|