|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound Samples & Downloads

|

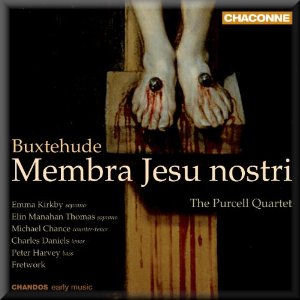

Dietrich BUXTEHUDE (c.1637-1707)

Membra Jesu nostri (BuxWV 75) [65:15]

Laudate, pueri, Dominum (BuxWV 69)* [4:56]

Matthias WECKMANN (c.1616-1674)

Kommet her zu mir alle** [8:42]

Elin Manahan Thomas*, Emma Kirkby* (soprano), Michael Chance (alto), Charles Daniels (tenor), Peter Harvey** (bass)

Elin Manahan Thomas*, Emma Kirkby* (soprano), Michael Chance (alto), Charles Daniels (tenor), Peter Harvey** (bass)

The Purcell Quartet, Fretwork

rec. 3-5 December 2009, St Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London, UK. DDD

CHANDOS CHAN 0775 [78:56]

CHANDOS CHAN 0775 [78:56]

|

|

|

The cantata cycle Membra Jesu nostri is a most remarkable

work. Its text is something one wouldn't expect to be set to

music by a composer of Lutheran orientation. It is based on

Rhythmica Oratio, a collection of hymns which address

the parts of the body of Christ hanging on the cross. This collection

was attributed to the medieval mystic Bernard de Clairvaux (1091-1153),

but today is generally thought to have been written by the Cistercian

monk Arnulf de Louvain (c1200-1250). The fact that these mystic

texts were used by a Lutheran composer can be explained by the

fact that Martin Luther held Bernard de Clairvaux in high esteem.

The Lutheran theologian Johann Arndt (1555-1621) played a crucial

role in the spreading of Bernard's mysticism in the world of

Lutheranism. He also translated the Rhythmica Oratio

into German. During the 17th century this aspect of Lutheran

thinking was enforced by the rise of pietism, which was in favour

of making way for subjective sentiments of fervour, compassion

and emotion.

These are present in abundance in this cantata cycle. The seven

parts of Christ's body are ordered from the perspective of someone

standing at the foot of the cross and looking upwards. First

he looks at his feet, then his knees, hands, side, breast, heart

and at last his face. Every cantata begins with a dictum,

a passage from the Bible, which for the most part cannot be

linked directly to Jesus' Passion at the cross, but rather refers

to a particular part of the body.

All cantatas have the same structure: they start with an instrumental

sinfonia, which is followed by the dictum, set in the

form of a concerto for 3 to 5 voices. Next is an aria of three

stanzas for solo voices, mostly supported by basso continuo

alone, and divided by instrumental ritornellos. At the end the

dictum is repeated, with the exception of the last cantata,

which ends with an 'Amen'. The sixth cantata is different: whereas

in all cantatas the instrumental ensemble consists of two violins

and bc, in this cantata the voices - here reduced to three -

are supported by five viole da gamba and bc. This different

scoring indicates that this cantata, Ad cor (To the heart),

is literally the heart of the cycle. The cyclical character

of this work is underpinned by the keys in which the seven cantatas

are written.

There are many recordings of this work on the market. They often

differ in scoring: in some the tutti are performed with a choir,

whereas in others the soloists are joined by ripienists

in the tutti. The present recording is strictly performed with

one voice per part: the five soloists also sing all the tutti

episodes. It is impossible to say which approach is historically

most plausible. We don't know when and where this work was performed

in Buxtehude's time, and with how many singers. Buxtehude dedicated

this work to his "honoured friend" Gustav Düben (c.1629-1690),

who was Kapellmeister at the Swedish court. Perhaps the

composition was a commission by Düben, who greatly admired Buxtehude

and was an avid collector of his works. It is therefore likely

that the Membra Jesu nostri was first performed in Stockholm.

And although it is not impossible that Buxtehude himself has

performed this work as well, it was certainly not sung during

the liturgy. And considering its intimate character a performance

during the Abendmusiken is also not very likely.

This last aspect makes me think that a performance with a small

vocal ensemble, with five singers or with ripienists

does most justice to the spirit of this work. It isn't that

easy to perform it really well. Membra Jesu nostri is

a work of great expression, but not in an operatic way. It is

crucial that the meditative, pietistic character is respected.

The text should be in the centre, and that means that the delivery,

the articulation and the accentuation is of the highest importance.

And that is where this recording disappoints. Some passages

come off very well, for instance the opening tutti of Ad

manus, 'Quid sunt plagae istae'. In that same cantata the

third stanza of the aria is also really expressive. That is

scored for alto, tenor and bass, and episodes in this scoring

are the most convincing parts of this performance. That is mainly

due to Charles Daniels and Peter Harvey whose articulation and

accentuation of single words and syllables is mostly very good.

Michael Chance is less convincing here, as he sings more legato

and with little dynamic differentiation. The differences between

these three are becoming crystal clear in the aria from Ad

pectus, where each of them sings one stanza. But their voices

blend very well, and that is not the case with the two sopranos.

Elin Manahan Thomas uses too much vibrato and that not only

damages her solos; the tutti episodes also suffer. Moreover

she sings too much legato and doesn't do enough with the text.

Emma Kirkby is much more convincing in this department as she

sensibly differentiates between words and syllables. Her diction

is impeccable, as always.

The role of the instruments seems limited as they mostly only

play the sinfonias and the ritornellos. But these instrumental

parts are quite expressive. The viols are crucial in the sixth

cantata, and the second cantata, Ad genua, begins with

a sonata in tremulo. In particular in German music of

the 17th century the tremolo was a device which was often used

in passages of strong emotion. The Purcell Quartet's playing

of this sonata is rather feeble, and lacks expression. That

is a general feature of the instrumental parts: they are rather

pale and dynamically too flat.

The addition of the two pieces by Buxtehude and Weckmann is

a little odd, as they are not connected to Passiontide. They

have probably been chosen because of the instrumental scorings.

Laudate, pueri, Dominum by Buxtehude is set for two sopranos

with five-part viol consort and bc, whereas Weckmann's sacred

concerto Kommet her zu mir alle is for bass solo with

two violins, three viole da gamba and bc. Buxtehude's cantata

is a setting of Psalm 113 (112, Vulgata): "Praise ye the

Lord". It is a beautiful piece, but the performance is

again disappointing because of Ms Thomas's vibrato. Her voice

and Ms Kirkby's don't blend that well, and as a result there

is too little ensemble. Weckmann's concerto is much better:

the solo part is quite virtuosic, with many melismatic passages

which show that Weckmann was influenced by the modern concertante

style from Italy. Peter Harvey gives an impressive account of

the bass part, and his articulation and pronunciation are immaculate.

And for some reason the playing of the Purcell Quartet and Fretwork

is much better here than in Buxtehude's Membra Jesu nostri.

The booklet includes all texts with translations in English,

German and French.

It is a shame that the main work on this disc doesn't achieve

a really satisfying performance sufficient to explores its depth

of expression. The best recording with solo voices is by Cantus

Cölln (Harmonia mundi).

Johan van Veen

|

|