|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT |

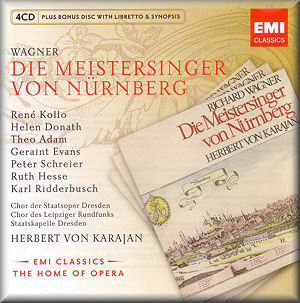

Richard WAGNER

(1813-1883)

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1867)

Hans Sachs - Theo Adam (baritone)

Hans Sachs - Theo Adam (baritone)

Veit Pogner- Karl Ridderbusch (bass)

Sixtus Beckmesser - Geraint Evans (baritone)

Walther von Stolzing - René Kollo (tenor)

David - Peter Schreier (tenor)

Eva - Helen Donath (soprano)

Magdelene - Ruth Hesse (mezzo)

Eberhard Büchner (tenor), Horst Lunow (bass), Zoltan Kélémén

(bass), Hans-Joachim Rotzsch (tenor), Peter Bindszus (tenor), Horst

Hiestermann (tenor), Hermann-Christian Polster (bass), Heinz Reeh

(bass), Siegfried Vogel (bass), Kurt Moll (bass)

Choirs of Staatsoper Dresden and Leipzig Radio

Dresden Staatskapelle/Herbert von Karajan

rec. November and December 1970, Lukaskirche, Dresden. ADD. 1999

digital remaster

EMI CLASSICS 6407882 [4 CDs: 70:21 + 72:14 + 70:45 + 52:22

+ CD ROM]

EMI CLASSICS 6407882 [4 CDs: 70:21 + 72:14 + 70:45 + 52:22

+ CD ROM]

|

|

|

Two recordings of The Mastersingers dominated the catalogue

when this magnificent performance was released in 1971, both

of them, as this one, on the EMI label. An earlier Karajan

and a reading by Rudolf Kempe are both still available, but

this one from Dresden was in stereo, which rather clinched the

matter for many collectors. The present release is not its first

CD reincarnation, having previously been included in EMI’s

Great

Recordings of the Century series. It is now available

at an absurdly low price, for which we must be grateful. Yet

texts and translations are available only on a “bonus”

CD; this is a poor solution. Reading Richard Osborne’s

excellent background article poses no problems, but if you want

to follow the words you’ll need to sit in front of a screen,

or, of course, print them out, all 111 pages of them.

The Dresden sound is glorious, and perfectly suited to the work.

All the same, not having heard this performance since the LP

era, I found it less sumptuous than I expected, a sign of the

wonders we have become used to. The recording is magnificent,

nonetheless, in a gently reverberant acoustic and with every

thread of orchestral and vocal detail audible. There is an intimacy

about it too, which matches the performance. One would not go

so far as to call it small-scale Wagner, but neither does the

word ‘monumental’ come to mind. There is a certain

mercurial lightness about Karajan’s vision of the work

that comes over very successfully in the performance and which

is perfectly preserved by the recorded sound.

Helen Donath is totally successful, young and eager: hers is,

in my view, a near-perfect realisation of Eva. I very much enjoyed

Ruth Hesse’s portrayal of Magdalene too. Peter Schreier

as David might seem like luxury casting, and so it is, his voice,

that of a lieder singer rather than an operatic tenor, perfectly

suited to the character. As to the mastersingers themselves,

there is not a weak link amongst them, and in particular, Karl

Ridderbusch as Eva’s father, Pogner, is absolutely outstanding.

The voice itself is one of remarkable beauty, rock-steady, and

he assumes the role with a noble authority which is very convincing

and affecting. The tenderness with which he conducts his Act

2 dialogue with his daughter is most moving. I wanted to like

Geraint Evans’ Beckmesser more than I did. There is no

doubt that the character is very vivid and entertaining, but

others have found more humanity there, and I do wish he had

tempered the tendency to near-speech, and actually sung more

of the notes. René Kollo as von Stolzing is very successful

indeed. His singing of the Prize Song is very beautiful, and

he is in slightly better voice there, perhaps understandably,

than in the singing lesson with Sachs, delightfully deft and

comical from both artists, in Act 2. It is known that Karajan

deliberately sought out younger voices for these roles, and

this pays off in Kollo’s case, particularly in those long

conversations earlier in the work, where he is excitable and

ardent, his sudden, overpowering love for Eva very well caught

and acted. When the set was released it was Theo Adam as Sachs

who garnered the least support amongst the different critics,

and so it proves for me too. The main problem is that this marvellous

singer’s voice is simply not right for Sachs. There is

not enough gravity or richness about it, nor warmth of tone.

Sachs is not simply a wise, old father-figure. He is a philosopher

and visionary, but also a cobbler, a fixer, a schemer; he is

even allowed a little flirting. In many of these scenes Adam

is excellent, but Sachs’ wisdom and force of character

provoke the crowd to a final hymn of praise, and in this performance

one can’t quite see why. The chorus is excellent, the

orchestra remarkable, and Karajan, as previously noted, leads

a performance quite different in character from much of his

work in Berlin, with unexceptional but convincing tempi and

not one hint of indulgence.

If an ideal Mastersingers exists on record, I haven’t

heard it. There is hardly a weakness in the marvellous Rudolf

Kempe’s cast, but this opera does need modern sound. This

Karajan performance was followed in quick succession by two

others, Solti on Decca and Jochum on DG. Solti’s performance

has what is for me the finest Sachs of all in the great Norman

Bailey, but others in the cast are less successful, and not

everybody warms to Solti’s rather excitable and foursquare

conducting. Jochum, on the other hand, is marvellous, with Fischer-Dieskau

as Sachs, self-recommending, though the voice itself is so characteristic

that one can never forget it is Fischer-Dieskau. The Knight

is played by Placido Domingo, a surprising choice, but highly

successful, leaving nobody in any doubt that he will win the

Prize! I haven’t heard Solti’s later recording from

Chicago (Decca), but it was well received, the conductor apparently

better attuned to the work this time around. I think I should

enjoy José van Dam as Sachs, and I know I should appreciate

Ben Heppner as von Stolzing, as he is excellent in the Sawallisch

recording on EMI, a very good all-round recommendation despite,

to my ears, a certain lack of intensity and character.

No ideal Mastersingers, then, but this one will do very

well for those untroubled by a less than sympathetic Sachs.

For this listener, the crucial factor in this life-enhancing

opera is the conductor. He must lead the performance as if in

one breath, allowing Wagner’s great paragraphs to pass

almost in an instant. For this, masterly control of pace and

phrasing is required. Of the performances I have heard, Eugen

Jochum comes closest to this near-unattainable ideal.

William Hedley

|

|