|

|

|

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

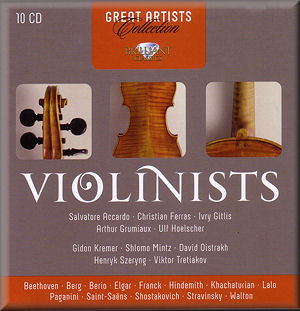

Great Artists Collection: Violinists

Concertos by Beethoven (Szeryng),

Elgar and Walton

(Accardo), Berg (Gitlis),

Shostakovich concertos

1 and 2 (Oistrakh), Saint-Saens concertos

1 and 2 (Hoelscher), Lalo Symphonie

Espagnole and Vieuxtemp Fifth

concerto (Mintz); Paganini 1

and Khachaturian (Tretiakov).

Sonatas and other chamber pieces: Beethoven

sonatas Op.25 Spring, and Op.30/1 and 2 (Grumiaux),

Frank and Lekeu (Ferras) and a mixed recital of Paganini,

Ernst, Bartok, Stravinsky, Stravinsky, Berio, Shchedrin, Dinicu

and Saint-Saens (Kremer).

David Oistrakh, Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra (Yevgeny Mravinsky),

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra (Gennady Rozhdestvensky), Arthur Grumiaux,

Clara Haskil (Piano), Christian Ferras, Pierre Barbizet (Piano),

Ivry Gitlis, Pro Musica Symphony, Vienna (William Strickland), Westphalia

Symphony Orchestra (Hubert Reichert), Concerts Colonne Orchestra

(Harold Byrns), Viktor Tretiakov, Estonian State Symphony Orchestra

(Neeme Järvi), Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra (Dmitri Tulin),

Henryk Szeryng, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (Bernard Haitink),

Gidon Kremer, Maria Bondarenko (Piano) Tatiana Grindenko (Violin

II) Oleg Maisenberg (Piano), Ulf Hoelscher, Ralph Kirshbaum (cello),

New Philharmonia Orchestra (Pierre Dervaux), Salvatore Accardo,

London Symphony Orchestra (Richard Hickox), Shlomo Mintz, Israel

Philharmonic Orchestra (Zubin Mehta)

David Oistrakh, Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra (Yevgeny Mravinsky),

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra (Gennady Rozhdestvensky), Arthur Grumiaux,

Clara Haskil (Piano), Christian Ferras, Pierre Barbizet (Piano),

Ivry Gitlis, Pro Musica Symphony, Vienna (William Strickland), Westphalia

Symphony Orchestra (Hubert Reichert), Concerts Colonne Orchestra

(Harold Byrns), Viktor Tretiakov, Estonian State Symphony Orchestra

(Neeme Järvi), Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra (Dmitri Tulin),

Henryk Szeryng, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (Bernard Haitink),

Gidon Kremer, Maria Bondarenko (Piano) Tatiana Grindenko (Violin

II) Oleg Maisenberg (Piano), Ulf Hoelscher, Ralph Kirshbaum (cello),

New Philharmonia Orchestra (Pierre Dervaux), Salvatore Accardo,

London Symphony Orchestra (Richard Hickox), Shlomo Mintz, Israel

Philharmonic Orchestra (Zubin Mehta)

rec. DDD?ADD

Full Contents List at end of review

BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9201 [10 CDs]

BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9201 [10 CDs]

|

|

|

This set of ten CDs appears, as usual with Brilliant, at a remarkably

cheap price. There is no booklet, and recording details given

on each slip-case are sketchy.

Choosing the works for a compilation such as this might seem

like a dream job, but in reality there will be considerable

constraints according to what is available and what permissions

can be granted. There are certainly a few questionable decisions

here, at least for this listener, and whether this set appeals

or not will depend rather more, I think, on the choice of works

than on the list of performers.

The performance of Shostakovich’s First Concerto on the

first disc seems to be the same one as appears on Chant du Monde

(LDC278882) from the late 1980s. I say “seems” because although

several interpretative details are identical, they soon get

out of sync if you play them at the same time on two machines.

Makes you wonder. In any event, the sound on the earlier incarnation

is execrable, whereas this transfer, whilst preserving a certain

glassy hardness and the forward placing of the soloist, is more

than acceptable. The work was composed for David Oistrakh (1908-1974),

and his performances, several of them recorded, will serve as

examples to generations of violinists to come. One is struck

in the first movement by the violinist’s astonishing power in

double stops and in anything above the stave. Rare are those

who manage to work up such a head of steam in the final pages

of the Scherzo. The Passacaglia is played with heartbreaking

eloquence, and the madcap yet strangely moving finale is sensational.

The Second Concerto, like the Second Cello Concerto,

is a more equivocal work, but one which rewards patience and

study. This is a live performance, complete with a few coughs,

scuffles and applause at the end. Oistrakh seems strangely ill

at ease in the opening paragraphs, and the performance as a

whole takes a little time to settle down. The sound is not great,

the various timpani and tom-tom strokes really rather unpleasant,

and the performance recorded a month earlier at the Proms with

the USSR State Symphony Orchestra under Svetlanov, available

on BBC Legends, is certainly preferable.

Arthur Grumiaux (1921-1986) has long been one of my favourite

violinists, but I had never heard any of his Beethoven sonata

performances with Clara Haskil, recorded for Philips when he

was in his mid-thirties. They are very fine, with playing of

impeccable poise and refinement from both artists. The three

sonatas have been carefully chosen, the genial Spring

contrasting well with the darkly dramatic C minor. There

are, of course, individual movements – or moments – one might

prefer in alternative readings. For my part, I think there is

rather more muscle to the music of the charming variations finale

of Op. 30 No. 1 than these performers find. But otherwise

the only serious drawback is the sound: the violin is well forward,

and the piano appears to have its own, quite different, acoustic.

More than once we have the distressing phenomenon, when the

piano has the main line and the violin accompanying figuration,

of hearing one of the finest violinists of the century apparently

playing exercises. I hope collectors acquiring this set with

be encouraged to explore further the work of this master violinist,

all the same.

Hearing Christian Ferras (1933-1982) in Franck’s Sonata

is a real treat. Unfailingly pure of tone and secure of intonation,

with a rapid vibrato that adds to the intensity, especially

in the upper reaches, the French violinist’s playing is just

what is needed to bring out the best in this masterly work.

Some listeners find the excitable scherzo somewhat overwrought,

but I can take it, and Ferras plays it for all it is worth.

The first movement, on the other hand, is a near-perfect blend

of lyrical ease and dramatic intensity, and Ferras brings out

both these qualities to perfection. Only in the finale did I

think that a slightly more relaxed tempo might have underlined

the heart’s-ease nature of the canonic passages whilst leaving

the more robust, exciting music intact. Guillaume Lekeu was

one of Franck’s pupil’s at the Paris Conservatoire. His Violin

Sonata is less distinctive than that of his teacher, which

is almost inevitable given his age. There are some lovely moments

though, especially in the slow movement, in 7/8 time form much

of its length. The other movements contain much energy, with

a few novel sonorities and some fairly conscious virtuoso writing.

Ferras, and of course his pianist Pierre Barbizet – Ferras rarely

played with anybody else – play the work with total conviction,

and these two sonatas, like the Grumiaux collection, represent

an excellent starting point for an exploration of the work of

this remarkable artist.

The reading of the Berg Concerto by Israeli violinist

Ivry Gitlis (b.1922) was knew to me; it is one of the finest

I have heard. The first movement alternates eloquently between

songful sorrow and ardour, whereas the anger as the second movement

opens is palpable. The Bach choral arrives with something of

a bump in many performances, but the moment is beautifully managed

here, the preceding climax hardly finished with, so that the

choral almost steals in. The soloist’s playing is technically

staggering, the only ugly sounds confined to those places where

the composer clearly intended them. The recording is more than

acceptable for the period, textures becoming opaque and ill

defined only at the second climax of the second movement. The

orchestra plays superbly, and the composer’s markings respectfully

followed. Some people find Hindemith’s Concerto somewhat

intractable, but this is another excellent performance and one

which very successfully brings out the work’s lyrical qualities.

The disc is completed by another very fine performance, this

time of Stravinsky’s glorious – and gloriously loopy – Concerto.

The sound here is a fairly major drawback, however; it sounds

strangely synthetic and there are strange balances resulting

in passages where important elements in the orchestra are all

but inaudible.

We’re all allowed our musical blind spots, and I’d have preferred

to hear the Siberian Viktor Tretiakov (b. 1946) in almost any

other repertoire than Paganini’s First Concerto, especially

when one reads the tempting list of works included in the Brilliant

boxed set devoted to him. It’s a remarkable performance though,

recorded live, with every technical demand apparently met with

ease. Khachaturian’s Concerto is another matter, and

although I haven’t heard any of the more recent performance

of this striking and colourful work, it’s difficult to imagine

how they can be superior, and this in spite of the ropy sound,

also live, with a fair selection of noises off, thumps and bangs

and the woodwind at times almost comically distant.

The first movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto from

Polish violinist Henryk Szeryng (1918-1988) is magnificent,

playing of enormous stature, remarkably successful in bringing

out the work’s dramatic side without in the least sacrificing

the lyrical. There are a host of interpretative details suggesting

that both soloist and conductor – Haitink and the Concertgebouw

are outstanding – had thought about the work anew. The recording

is very fine, but the violin is rather too far forward, and

this, combined with the soloist’s reluctance to play really

quietly makes for a slow movement rather lacking in magic or

inwardness, and a finale that seems too intent on robustness

at the expense of charm and – what Beethoven requests – delicacy.

Then there are a few seconds of dead silence between these two

movements that effectively ruin whatever atmosphere the soloist

has been able to create. I had high hopes for this disc, but

it was ultimately disappointing. The Romances come off

well enough, but even whilst admitting that it is difficult

to make anything more of them than pleasant, undemanding pieces,

the playing does seem routine here.

The disc devoted to Gidon Kremer (b. 1947) is a missed opportunity.

Paganini’s Cantabile is a pretty enough tune, but the

unaccompanied Caprices have always seemed to my ears

a series of thoroughly nasty noises, and not even the great

Estonian can convince me otherwise. Most of the pieces on this

disc have been recorded in concert, and are unaccompanied. It

is very hard going. The two pieces by the Moravian virtuoso

Ernst are technically brilliant, especially the transcription

for solo violin of Schubert’s masterpiece, but why anyone would

ever want to listen to them, and even more, want to learn to

play them, is a mystery. Stravinsky’s Elegy, for viola,

not for violin as given on the cover, is an affecting piece

but marred, as are several of the performances on this disc,

by noises from the live audience. The three Berio pieces, played

with Tatiana Grindenko, suffer in a similar way and would benefit

from being heard in a different context. The pieces by Shchedrin

and Dinicu are perhaps the most interesting on the disc.

If you enjoy the melodious confections of Saint-Saëns, the disc

devoted to German violinist Ulf Hoelscher (b. 1943) will be

pure pleasure. Virtually all this music requires remarkable

virtuosity from the soloist at one moment or other, and this

Hoelscher provides in spades. His intonation is spot on, even

in the most hair-raisingly rapid passages, and in the more melodic

ones he plays with a ravishing, singing tone. It is difficult

to imagine this music better done, and the orchestral support

under Pierre Dervaux, is outstanding. The recording is excellent

too, with near-perfect balance between soloist and orchestra,

and only a Jumbo-sized harp in the slow movement of the C major

Concerto provoking adverse comment. Several of these works may

be unfamiliar even to experienced listeners, and it is a pleasure

to recommend in particular the remarkable violin and cello duo,

La Muse et la Poète, in which the violinist is most poetically

partnered by Ralph Kirschbaum.

Italian violinist Salvatore Accordo (b. 1941) should have been

perfectly suited to the Italianate warmth of Walton’s Concerto,

but as it turns out, the Elgar is the finer of the two performances.

It gets off to a bumpy start with an orchestral introduction

in which Hickox fails to establish an integrated pulse, fine

though the playing is. Then Accardo’s way is strangely detached

and cool, but one gets used to it as a valid alternative view.

His tone, rich and full in the lower registers, has a certain

thinness above the stave, however, that will not please all

listeners. The less inspired passages in the first movement

development section do not always convince here, and tension

flags from time to time in the finale too, but overall this

is an impressive reading which, whilst not up there with the

finest, is certainly an interesting addition to any collection.

The Walton is less successful. Problems of intonation, little

more than a suspicion in the Elgar, here become seriously troubling;

one of the most glorious moments of this glorious score, the

return of the second subject of the finale, is more or less

ruined. The very opening, a gift of a melody, is played with

little character or expression, and much of the playing throughout

seems routine. Kyung Wha Chungs’s performance of this piece,

with Previn, has never been surpassed in my opinion, and this

one is very pale by comparison. Recording details are not given,

but these performances first appeared on Collins Classics in

the early 1990s.

If the repertoire appeals you can hardly go wrong with the final

disc, devoted to Israeli violinist Shlomo Mintz (b. 1957), and

a straight reissue of a DG disc. Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnole

gives ample opportunity to demonstrate dazzling technique, whilst

possessing considerably more musical interest and charm than

many a virtuoso piece. Mintz is indeed dazzling in the more

challenging passages, but is also particularly convincing in

the gentler, more lyrical passages such as the various second

subjects, where his rich tone and intense yet pleasing timbre

are great assets. There is nothing profound here, and the Vieuxtemps

Concerto is even slighter fare, but Mintz makes as much

of it as can be made, and more than many violinists would achieve.

The famous Saint-Saëns piece rounds off an enjoyable disc.

William Hedley

And a further review of this set from Rob Barnett

Brilliant Classics again prove themselves masters of the art

of cutting their cake along as many planes as possible. No one

could accuse them of not maximising their yield on recordings

licensed to them. And, by the way, that’s not a complaint. Listeners

with exploring minds and timid wallets benefit so long as they

get to grips with what they are getting for their small outlay.

CD 1

The two Shostakovich concertos are signature works for

Oistrakh. The first was written in 1947-48 yet not premiered

until 1955. The Scherzo is an exercise in macabre grotesquerie.

It romps along with scathing sparks flashing and flying. These

are surely not radio recordings and there is no applause. Hearing

the finale of the Passacaglia-Burlesque driven and goaded

along by Mravinsky I am sure Shostakovich must have had the

example of the Khachaturian concerto in mind. The sounds of

Rachmaninov's The Bells echo through the gunfire-convulsive

ending. The Second Violin Concerto was written as a birthday

offering to Oistrakh on his sixtieth. Written in 1968 the world

it inhabits is filled with foreboding and haunted uncertainty.

It is a difficult work to get into. That said Rozhdestvensky

gives fantastic support through the Moscow Phil and the drum

cannonades are given with deafening emphasis at 10.01. The work

ends with rapped-out volleys and gritted teeth ruthlessness.

There is applause this time.

CD 2

The patrician Grumiaux is heard here in three Beethoven sonatas

through pebble-hard and boxy 1956-7 analogue. This is Beethoven

given a classical spin and a somewhat hissy spin at that . It’s

an occasionally testing listen. Brace yourself.

CD 3

This disc offers better analogue sound. The experience is so

much sweeter in these lively and sun-drenched performances from

Ferras and Barbizet. They trounce the demands of the Franck

Allegro’s sprinting pulse. Ferras sounds even sweeter

in the songful Allegretto Poco Mosso. I am pleased to

see the sadly short-lived Lekeu putting in an appearance. As

a composer he lavishly splashed across three wonderful discs

in the recent 50CD Cyprès set from the Liège Phil – don’t miss

it – there are copies on Amazon. Lekeu is here represented by

his meaty Violin Sonata. It is ecstatically romantic stuff but

slim-limbed and elegant. Ferras is a stirring and muscularly

fine player with plenty of projection but also restraint and

taste.

CD 4

We encounter mono (1953-62) on this disc from Ivry Gitlis. His

is not a big name but clearly one well worth knowing. His Berg

is penetrating yet tender - one of the loveliest of versions

even if the sound is getting on for sixty years old. The Hindemith

is only half a century old and is vibrant, close-up and clean

allowance being made for a discreet bed of hiss. The Hindemith

is surprisingly beefy. However the Stravinsky is beginning to

show its age though the performance is full of salty vim and

caustic vigour.

CD 5

Tretiakov is heard in a live concert complete with coughs and

throat-clearing in the bombastic Paganini Violin Concerto No.

1 with lapel-grabbing sound. Sparks fly all over the shop as

he scuds, accelerates and smashes his way though the challenges

of this showpiece. Ten years before the Paganini we hear Tretiakov

in the Khachaturian. The sound is not as vivid as for the Paganini

and the soloist’s slenderness of tone seems undernourished by

comparison with the various Oistrakhs and indeed Tretiakov's

own self in the Paganini.

CD 6

Szeryng's 1973 Beethoven concerto is recorded with a pleasing

sense of spatial image and a good audio spread across the speakers.

The performance is strong on old style Olympian loftiness and

philosophical song. Szeryng is intimately recorded and the whole

image and effect is very agreeable. It’s all in wonderful analogue

sound and the same goes for the slighter two Romances.

CD 7

Gidon Kremer is caught well outside what we now regard as his

‘zone’ in radio recordings made while in the Soviet Bloc. These

are all showpieces of which I got the most from the Stravinsky

Elegy for solo violin and this despite the coughing of

one member of the audience. I cannot work out what is happening

with the de Bériot three duets though I think he achieves the

two lines through double-stopping rather than two track recording.

Shchedrin's In the Style of Albeniz was possible a sketch

or a companion piece for his style in the Carmen ballet written

for his wife Maya Plisetskaya. He tosses off a wildly fume-wreathed

Hora staccato. Spectacularly witty and exemplifying mechanistic

mastery is the extract from Carnaval des Animaux complete

with applause. These tracks span 1967 to 1990.

CD8

Listen to the eager acceleration of Hoelscher in the finale

of the Griegian First Concerto which, but for its name

and three movements, could easily have passed for one of the

nine short genre pieces which fill out the two discs around

the core of the three concertos. This is a short work (almost

12 minutes) of shivering Beethovenian fire - full of incident

and invention. Bruch's First Concerto is a model (conscious

or unconscious) for these concertos. Bruch also wrote three

but it was his first that held the high ground while his other

two languished. In the case of Saint-Säens the Third has

found a place in record catalogues while the other two have

had to struggle against the odds. The Second Concerto has

an Ossian-inflected andante espressivo with harp figures

lending depth to a sentimentality teetering close to Bruch's

Scottish Fantasy. This makes way for a dashing Polacca

scherzando with sideways glances towards Beethoven's 'dance

apotheosis' - Seventh Symphony.

La Muse et le poète is a sober double concerto

in which Ralph Kirshbaum's cello cuts a deeper path than the

violin. This is soulful, not in the manner of Bruch's Kol

Nidrei, but rather like the Beethoven Violin Concerto yet

with a Tchaikovskian honeyed nostalgia over the proceedings.

The explosive little Valse-Caprice is as arranged

by Ysaÿe. The two Romances are just that: well

rounded, not impulsive, musing and touching though lacking a

strong profile.

CD 9

You would be hard-pushed to better this disc as a coupling.

It brings together two grand English violin concertos. The recording

is clear and potent whether in sotto voce musing from

the solo or in tingling shivers in the finale of the Elgar.

I first became aware of Accardo from his pioneering DG set of

the Paganini violin concertos with the LPO and Dutoit. I recall

Accardo being centre-stage in a late night relay by BBC Radio

3 of the Elgar concerto with (I think) the Boston Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Colin Davis. That would have been circa 1974 and

it was one of those gutsy transformational performances that

scored its way deep into the memory. Almost two decades later

this disc appeared or more accurately the Collins Classics CD

original on 13382 (reissued on Regis and Alto). Speaking from

fading memory this Elgar is not quite as molten as the

broadcast version but it is a very strong contender. My all-time

favourite is the Heifetz with a for once inspired Sargent leading

the very same orchestra as appears here. Looking at the Elgar

alone I also rate highly the Zukerman with Barenboim (1970s

CBS), the two Kennedy recordings (EMI), Bean (EMI) and Haendel

(BBC Radio CD rather than Testament). The last four minutes

of the Elgar both nourish the heart with nobility and excite

with adrenaline. The Walton is also good with tempos at times

pushed somewhat but with leeway afforded Accardo for amorous

rhapsodising. This is another good performance with equally

fine attention to transparency and audio fidelity. Hickox and

Accardo take their time most satisfyingly in the dreamy ostinato

in the middle movement making the zest and flitter of the presto

sections all the more effective. In the finale seductive tenderness

(4:20) meets rapturous grandeur. A generous pairing which majors

on inspiring playing from Accardo and colleagues matched with

a refined yet leonine recording.

CD 10

Shlomo Mintz offers a slender and sweetly sustained Symphonie

Espagnole superbly if distantly recorded in Tel Aviv in

1988. His Vieuxtemps is more closely recorded but I find little

in it to hold the attention. The Saint-Saens is a staple of

the recording studio - less so of the concert hall where such

short morsels struggle to find a place. Mintz does this rather

neatly and connects with the Spanish business of the Lalo.

Recording quality varies quite a bit but it's always at least

listenable. Two discs of the ten are in digital sound. There

are no liner notes but fairly full discographical details are

given on each sleeve.

People fulminate about Brilliant but there is no detriment in

their purely commercial approach. They are after all in business.

Their multifarious re-packagings and re-couplings of the library

they have licensed from hither and yon can confuse but the prices

are right. The presentation of these recordings to different

audiences should win new friends for the music and keep alive

the reputations of Gitlis, Tretiakov and the rest.

This is an inexpensive outing among ten violinists of the twentieth

century and their repertoire both contemporary and nineteenth

century. It's a mixed bag but you will learn from and enjoy

much that is here.

Rob Barnett

Full Contents List

CD 1 [64:44]

David Oistrakh

Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1976)

Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77 (1948) [36:29]

Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra/Yevgeny Mravinsky

rec. 18 November 1956

Violin Concerto No. 2 in C sharp minor, Op. 129 (1967) [28:13]

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra/Gennady Rozhdestvensky

rec. 27 September 1968

CD 2 [68:22]

Arthur Grumiaux

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Violin Sonata in F major, Op. 24, “Spring” (1800/1) [22:47]

Violin Sonata in A major, Op. 31, No. 1 (1801/2) [19:56]

Violin Sonata in C minor, Op. 31, No. 2 (1801/2) [25:00]

Clara Haskil (piano)

rec. 1956/7, Vienna

CD3 [55:57]

Christian Ferras

César FRANCK (1822-1890)

Violin Sonata in A major (1886) [29:20]

Guillaume LEKEU (1871-1894)

Violin Sonata in G major (1893) [28:24]

Pierre Barbizet (piano)

rec. 1966 and 1968

CD 4 [70 :12]

Ivry Gitlis

Alban BERG (1885-1935)

Violin Concerto (1935) [23:51]

Pro Musica Symphony, Vienna/William Strickland

rec. 1953

Paul HINDEMITH (1895-1963)

Violin Concerto in D (1940) [24 :22]

Westphalia Symphony Orchestra/Hubert Reichert

rec. 1962

Igor STRAVINSKY (1882-1971)

Violin Concerto in D (1931) [21:09]

Colonne Concerts Orchestra/Harold Byrns

rec. 1955

CD 5 [75:18]

Viktor Tretiakov

Nicolo PAGANINI (1782-1840)

Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major, Op. 6 (c. 1817) [35:30]

Estonian State Symphony Orchestra/Neeme Järvi

rec. 11 November 1978

Aram KHACHATURIAN (1903-1978)

Violin Concerto (1940) [39:45]

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra/Dmitri Tulin

rec. 13 October 1967

CD 6 [63 :24]

Henryk Szeryng

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Violin Concerto in D, Op. 61 [25.09]

Romance No. 1 in G, Op. 40 [8:04]

Romance No. 2 in F, Op. 50 [9:26]

Concertgebouw Orchestra/Bernard Haitink

rec. 26/27 April 1973

CD 7 [52:52]

Gidon Kremer

Nicolo PAGANINI

Cantabile in D major [4:03]

Caprice No. 4 in C minor [6:26]

Caprice No. 17 in E flat major [3:42]

Heinrich Wilhelm ERNST (1812?-1865)

Variations on “The Last Rose of Summer”

Grand Caprice after Schubert’s “Erlkönig”

Béla BARTÓK (1881-1945)

Tempo di Ciacona, from Sonata for Solo Violin (1944) [7:55]

Igor STRAVINSKY (1882-1971)

Elegy for solo viola (1943) [4:57]

Luciano BERIO (1925-2003)

Duet for violins, “Leonardo” [1:33]

Duet for violins, “Annie” [0:38]

Duet for violins, “Aldo” [1:54]

Rodion SHCHEDRIN (b. 1932)

In the style of Albeniz (1973) [3:39]

Grigoras DINICU (1889-1949?)

Hora Staccato [2:19]

BORZO/BIHARI

Czardas in A minor [2:41]

Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835-1921)

Creatures with Long Ears (from The Carnival of the Animals) (1886) [1:02]

rec. 1967 – 1990

CD 8 [76:09]

Ulf Hoelscher

Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835-1921)

Violin Concerto No. 1 in A major, Op. 20 (1872) [11:43]

Violin Concerto No. 2 in C major, Op. 58 1902 [27:11]

Le Muse et le Poète, Op. 132 [15 :32]

Valse-caprice [7:10]

Romance in C major, Op. 48 [6:48]

Romance in D flat major, Op. 37 [5:53]

New Philharmonia Orchestra/Pierre Dervaux

rec. Abbey Road Studios, London, February 1977

CD 9 [77:01]

Salvatore Accardo

Edward ELGAR (1857-1934)

Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1910) [46:13]

William WALTON (1902-1983)

Violin Concerto (1943) [30:48]

London Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox

rec. Studio 1, Abbey Road, London December 1991

CD 10 [60:01]

Schlomo Mintz

Edouard LALO (1823-1892)

Symphonie Espagnole (1874) [31:48]

Henri VIEUXTEMPS (1820-1881)

Violin Concerto No. 5 in A minor, Op. 37 [19:01]

Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835-1921)

Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, Op. 28 (1863) [9:12]

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra/Zubin Mehta

rec. Frederic R. Mann Auditorium, Tel Aviv, 20-27 October 1988

|

|