|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

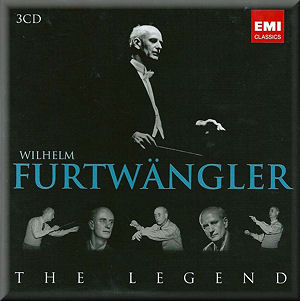

Wilhelm Furtwängler: The Legend

CD 1 [71:06]

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756-1791)

Symphony no.40 in G minor, K550 (1778) [24:11]

Joseph HAYDN (1732-1809)

Symphony no.94 in G Surprise (1791) [22:28]

Franz SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

Symphony no.8 in B minor, D759 Unfinished (1822) [23:55]

CD 2 [76:25]

Robert SCHUMANN (1810-1856)

Manfred, op.115 – overture (1849) [12:37]

Felix MENDELSSOHN (1809-1847)

The Hebrides – overture op.26 Fingal’s cave (1830)

[10:03]

Bedrich

SMETANA (1824-1884)

Má vlast – Vltava (1875) [12:38]

Carl Maria von WEBER (1786-1826)

Oberon overture (1826) [9:59]

Franz SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

Rosamunde D644 – overture (1820) [10:42]

Rosamunde D797 – incidental music (1823) [9:59]

Luigi CHERUBINI (1760-1842)

Anacréon – overture (1803) [9:41]

CD 3 [71:35]

Christoph Willibald von GLUCK (1714-1787)

Alceste – overture (1767) [8:45]

Iphigénie en Aulide – overture (1774) [10:05]

Carl Maria von WEBER (1786-1826)

Der Freischütz – overture (1821) [10:44]

Euryanthe – overture (1823) [9:29]

Richard STRAUSS (1864-1949)

Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche (1895) [16:17]

Franz LISZT (1811-1886)

Les Préludes (1848) [15:40]

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Wilhelm Furtwängler

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Wilhelm Furtwängler

rec. Musikvereinssaal, Vienna (all except Schubert D797) and Brahmssaal,

Vienna (Schubert D797); 7-8 Dec 1948 and 17 Feb 1949 (Mozart); 15

Feb 1949 (Mendelssohn); 19-21 Jan 1950 (Schubert D759); 1 Feb 1950

(Weber Oberon); 2 Feb. 1950 (Schubert D797); 3 and 17 Jan

1951 (Schubert D644); 11 Jan 1951 (Cherubini); 11, 12 and 17 Jan

1951 (Haydn and Gluck Iphigénie en Aulide); 24 Jan 1951 (Schumann

and Smetana); 3 March 1954 (Strauss and Liszt); March 1954 (Weber

Der Freischütz); 6 March 1954 (Weber Euryanthe); and

8 March 1954 (Gluck Alceste). ADD

EMI CLASSICS 50999 9 08119 2 0 [3 CDs: 71:06 + 76:25 + 71:35]

EMI CLASSICS 50999 9 08119 2 0 [3 CDs: 71:06 + 76:25 + 71:35]

|

|

|

This three-disc box set is issued in parallel with – and is,

no doubt, intended to act as a taster for – a far larger EMI

box set Wilhelm Furtwängler: the great recordings (14

CDs, EMI 9 08161-2). In this briefer survey, the first disc

focuses on core symphonic repertoire while the other two feature

a miscellany of overtures and orchestral favourites. The orchestra

throughout is the Vienna Philharmonic and the recordings are

all post-war – mostly set down on chilly winter days between

December 1948 and January 1951, but with a final burst of creative

activity in the first week or so of March 1954.

Almost all the recordings are well known. What is equally well

known, though, is that Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886-1954)

was a conductor who rarely felt comfortable in the studio. He

seems, on the contrary, to have been inspired to his greatest

levels of spontaneity and artistic imagination by the presence

– and reactions - of a live audience and the absence of the

technological restraints imposed by the recording process. As

a result, many of his most compelling and individually characterised

performances were given in concert halls and have, as a result,

either been lost forever or else preserved in less than ideal

sound.

The symphonies on CD 1 are very enjoyably done, though anyone

used only to modern historically-informed performance practice

will no doubt find them over-weighty and distinctly old-school.

Lacking the “subjective” indiosyncracies that characterise many

of Furtwängler’s live recordings – but that can become

somewhat irritating on repeated listening – these are relatively

straightforward accounts, though none is lacking in real distinction.

A notably driven Mozart G minor is most enjoyable; the affectionate

account of Haydn’s Surprise is especially warm and silky;

while Schubert’s Unfinished, in contrast, is serious

of purpose and darkly hued.

Of the overtures and miscellaneous orchestral works on CDs 2

and 3, none is less than expertly conceived and executed, though

whether they amount to essential examples of Furtwängler’s

artistry is at least open to question.

Furtwängler’s many admirers will, I imagine, be buying

the big 14-disc set referred to above and, apart from them,

I wonder whether there really is an audience for this smaller

box’s pick’n’mix approach. After all, as concert programmes

clearly demonstrate, from the 1950s onwards public taste has

veered away from overtures and orchestral showpieces towards

more substantial works, a development largely caused by the

change from 78s – well suited to shorter pieces but not to longer

ones – to LPs and then CDs. Thus, even as Furtwängler was

recording the pieces on these discs, they were on the verge

of falling out of favour.

By sheer coincidence, on the very day I completed this review

(17 May 2011), The Times reprinted its 1935 report of

the death of French composer Paul Dukas, in the course of which

the writer had observed that “... M. Dukas is known chiefly

by his popular orchestral scherzo L’Apprenti Sorcier without

which a Promenade season would be incomplete” [my

emphasis]. Could there be a more graphic illustration of how

times – and concert programming practices – have changed in

the past 76 years?

It is also worth noting that, although the sound on these studio

recordings, further enhanced by digital remastering in 1998,

is far better than we are used to on many discs of Furtwängler

recorded live, it still remains rather opaque (though there

is a marked improvement in the Rosamunde incidental music,

recorded in Vienna’s Brahmssaal). Unfortunately, EMI’s technology

at the time was just not up to the cutting edge standards being

forged by the likes of Decca.

Such musical miscellanies can be of interest – and I

have in the past given very warm welcomes on this site to similar

Furtwängler potpourris released on the Naxos Historical

label. But their primary value was in offering genuine and rare

insights into the performance practice and orchestral styles

and standards of the 1920s and 1930s. The 1950s Vienna Philharmonic,

by contrast, is already well documented on disc and, as already

mentioned, most studio accounts fail, in any case, to convey

the genuine essence of this particular conductor.

Wilhelm Furtwängler was without doubt, as the title of

this box set asserts, a musical legend, but I’m not sure that

you’d necessarily deduce as much by listening to these newly-reissued

recordings.

Rob Maynard

|

|