|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

|

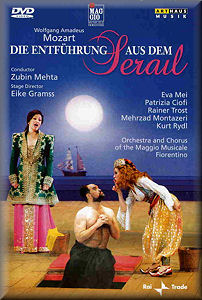

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART

(1756-1791)

Die Entführung aus dem Serail - Singspiel in

three acts K.384 (1782)

Bassa Selim (Pasha) - Markus John (spoken role by an actor)

Bassa Selim (Pasha) - Markus John (spoken role by an actor)

Konstanze, Spanish lady, beloved of Belmonte – Eva Mei (soprano)

Belmonte, Spanish nobleman, beloved of Konstanze – Rainer Trost

(tenor)

Blonde, maid to Konstanze – Patrizia Ciofi (soprano)

Pedrillo, Belmonte’s servant and overseer of Bassa's garden – Mehrzad

Montazeri (tenor)

Osmin, overseer of Bassa's villa – Kurt Rydl (bass)

Chorus and Orchestra of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino/Zubin Mehta

rec. live, Teatro della Pergola, Florence, 2002

Stage Director: Eike Gramss

Set Design: Christoph Wagenknecht Costume Design: Catherine Voeffray

Television Director: George Blume

Picture format: NTSC 16:9

Sound format: PCM Stereo. DTS-5.1. DD 5.1

Subtitles: English, German, French, Spanish, Italian

ARTHAUS MUSIC 107 109

ARTHAUS MUSIC 107 109  [136:00]

[136:00]

|

|

|

This opera is defined as a singspiel, a work of musical numbers

interspersed with spoken dialogue. Mozart had already had significant

success with his youthful Il re pastore and La finta

giardiniera, both presented in 1775. He seems to have got

into singspiel mode in Salzburg in the winter of 1779-1780 with

the revision of La finta giardiniera into Die gärtnerin

aus liebe. This involved the replacement of the sung recitative

by spoken dialogue as well as a change of language. He then

went further and began the composition of another work in this

genre. Perhaps influenced by the contemporary craze in Austria

and Prussia for all things Turkish, and ever-competitive, Mozart

might also have been keen to upstage Gluck’s harem opera La

Rencontre imprévue - a runaway success since its Viennese

premiere 1764. It is not known if he was commissioned to write

the work or the provenance of the libretto. However, after a

while and with no prospect of a staging, Mozart abandoned it.

Left without overture or final dénouement of a second act finale,

the incomplete opera came to be called Zaide.

Whilst Mozart might have been frustrated by the lack of opportunities

to stage his new singspiel, the summer of 1780 brought the commission

for a new opera seria. This became Idomeneo - a significant

success. Meanwhile, Gottlieb Stephanie, Stage Director at the

Burgtheater, the Court Theatre set up by Emperor Joseph II in

an attempt to promote singspiel, had been impressed with what

he had seen of Zaide. He had promised Mozart a new libretto

that would be even more congenial to him whilst also being on

the Turkish theme. This was Die Entführung aus dem Serail.

Mozart was greatly taken by the libretto and composed with

enthusiasm. In the work Mozart does not eschew formal musical

structures in pursuit of simplicity and does not hesitate to

include elaborate arias and complex textures in the orchestra.

Die Entführung aus dem Serail was premiered on

16 July 1782 and became his first truly outstanding

operatic success; its music is full of invention and vitality

as well as having particular vocal challenges for the heroine.

Mozart’s concern for the Turkish theme underlies the whole work

and is also reflected in the many additions he had made to the

original libretto.

At a personal level Mozart, after his split, not without some

rancour, from the Archbishop of Salzburg’s employment, and whilst

composing Die Entführung aus dem Serail, became engaged

to Constance the third of the four Weber girls and, in respect

of his fiancée, moved out of their house. They married on 4

August 1782. Wolfgang maintained the marital home by teaching

pupils of the nobility and as a composer including a number

of piano concertos and solo arias for friends. He appeared as

soloist before the Emperor whilst still thinking of opera and

reading many possible libretti.

I have always enjoyed this opera, which, whilst not the equal

of his later and greatest singspiel, Die Zauberflöte,

has many strengths. In recent years it has been rather neglected,

perhaps out of mistaken political correctness which has also

led to some rather quirky productions including one set on The

Orient Express; yes, a train for a harem - any thing or

gimmick is possible for some directors and designers. I could

not imagine how it could work and it didn’t (see review).

Similarly, Opera North treated the work as slapstick (see review).

I have to go back to the early 1980s when Glyndebourne produced

elegant sets by William Dudley alongside a touring cast that

brought the best out of Mozart’s creation. Those elegant sets

and production were caught on film at the main Festival and,

like this performance, has been issued on DVD (Arthaus 101 091).

This production is similarly true to Mozart in its elegant staging

of flown and moving screens, allowing for swift transition between

scenes, and with lighting effects adding to the colours and

aiding mood and setting. The costumes are in period and are

as opulent as the set. Yes, there is one little gimmick, but

it is inconsequential and I won’t spoil your surprise.

If the production virtues outlined above were not enough to

guarantee a successful and eminently recommendable performance,

the singing and conducting are of like quality. Zubin Mehta

is not a conductor I associate with Mozart. Conducting without

a score, as far as I could see in the occasional shot by the

skilful Video Director, Mehta does Mozart’s creation full justice

drawing scintillating playing of rhythmic brio and character

from his orchestra. Being the considerable opera conductor he

is, Mehta also supports his singers in the demanding arias,

duets and ensembles.

Mozart certainly makes considerable vocal demands on his singers

in this opera, none more so than on the imprisoned heroine Constanze.

Having warmed up in Ach ich liebte (Ch.11) she scaled

the heights in Traurigkeit (Ch. 19) and was well up to

the extended demands, in length and vocal range of Martern

aller Arten (Ch. 22). The tall and elegant Miss Mei is well

versed in the vocal demands of this role. After graduating from

the Conservatory Luigi Cherubini in Florence in 1989

she won the International Mozart Competition in Vienna for her

interpretation of Konstanze, making her debut in the same role

later in the year at the Vienna State Opera. Not only can she

sing the role she can also act the part too. Her demeanour as

the Pasha presses his suit and her expressions of anger at Belmonte’s

doubts are well expressed in body and facial language to match

her excellent singing. In the only slightly less vocally demanding

role of Blonde her compatriot Patricia Ciofi plays a feisty

girl well able to sort out Osmin’s carnal intentions. This Blonde

is in no mood to be influenced by his flexed six-pack after

he climbs from his steam bath (Chs.16-17). Her coloratura is

secure and is allied to a warm and womanly tone and convincing

acting.

The male singing trio is dominated by Kurt Rydl as Osmin. Vocally

he may not erase memories of Gottlieb Frick in the role. He

suffers from the odd moment of loose tone, but his acting of

the role is simply outstanding, conveying every nuance of the

nasty and bossy Osmin; an absolute delight. His bullying of

Pedrillo is well-played and not overdone, whist Mehrzad Montazeri’s

vocal and acted portrayal, particularly when tempting Osmin

to take some alcohol, is also worth mention. No political correctness

about tempting the Muslim Osmin to partake and go into prayer

mode at the name of the Prophet in this production (Chs.25-27).

Montazeri’s tenor is strong and he plays the demanding secondary

tenor role well without being overwhelmed in ensembles. His

final act romanza is well phrased (Ch. 33). As the lover Belmonte,

who comes to rescue Constanze, Rainer Trost’s strong tenor moves

easily between the demanding registers and with a welcome use

of some soft singing. His basic tone has an edge to it that

the microphone accentuates a little; he could be a little more

vocally mellifluous, but his ardent phrasing and involved acting

more than compensate (Chs. 8, 32 and in the act two and three

finales 29-30, 39 and 40). Trost’s vocal expression and acting,

as Belmonte comforts Constanze when they are faced with death,

is particularly notable (CH. 37).

Last but not least of the male contingent is the demanding spoken

role of Bassa Selim. This is a role that is by no means easy

to bring off. The actor has to play a convincing, even threatening,

suitor of Constanze in act one (Chs. 9-10) and then show dignity

after Selim’s magnanimity in freeing the intruders after discovering

one, Belmonte, is the son of his bitter enemy (Ch.38). Markus

John’s acting and spoken inflections fulfilled these varied

demands with conviction and sincerity.

The sound is well balanced and clear with the picture quality

of a similar high standard. Add the video director’s sensitivity

to all the nuances of the work and the imaginative lighting,

particularly in act three (Chs. 31-41) and this is an outstanding

issue.

There is an interesting essay about the background to Mozart’s

composition of this opera and its performance history in Italy.

This is given in English, French and German and adds to the

pleasure.

Robert J Farr

|

|