|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Violin Sonata No.1 in D, Op.12 No.1 (1797-98) [20:19]

Violin Sonata No.2 in A, Op.12 No.2 (1797-98) [16:15]

Violin Sonata No.3 in E flat, Op.12 No.3 (1797-98) [18:21]

Violin Sonata No.4 in A minor, Op.23 (1800) [16:12]

Violin Sonata No.5 in F, Op.24 'Spring' (1800-01) [23:21]

Violin Sonata No.8 in G, Op.30 No.3 (1801-02) [17:08]

Violin Sonata No.9 in A, Op.47 'Kreutzer' (1802-03) [36:47]

Violin Sonata No.6 in A, Op.30 No.1 (1801-02) [20:51]

Violin Sonata No.7 in C minor, Op.30 No.2 (1801-02) [24:16]

Violin Sonata No.10 in G, Op.96 (1812) [27:05]

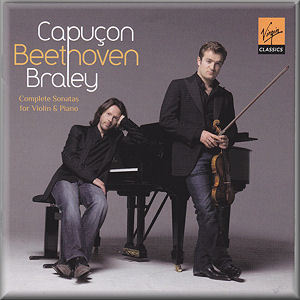

Renaud Capuçon (violin); Frank Braley (piano)

Renaud Capuçon (violin); Frank Braley (piano)

rec. September and October 2009, L’heure bleue, Salle de musique, La-Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland

VIRGIN CLASSICS 6420010 [3 CDs: 71:44 + 77:45 + 73:47]

VIRGIN CLASSICS 6420010 [3 CDs: 71:44 + 77:45 + 73:47]

|

|

|

Why add another set of the complete violin sonatas to your shelves?

If you’re historically minded you have the Kreisler/Rupp and

Heifetz/Emanuel Bay/Brooks Smith on your shelves. Possibly you’ve

dallied with Oistrakh/Oborin, or Schneiderhan/Kempff or Menuhin

and his pianistic partners. If you’re from the late LP era you

have the Perlman/Ashkenazy. If you’re a silver disc fanatic

you’ll certainly have acquired one of the more recent cycles;

it’s possible you even bought the recent Dumay/Pires set on

DG, and good for you if you did; it’s excellent. So what makes

this new cycle so special, and should you be interested?

Firstly, it’s been beautifully recorded, and the balance is

just right between the instruments. Second, the performances

are wonderfully lyrical and full of deft, imaginative and refined

gestures. The Spring Sonata is a most obvious place to start.

Gentle sensitivity is the way in which Capuçon and Braley play

it; bowing is quite light, articulation lacks much of the tensile

muscularity that other pairings bring to the music. The ethos

is a true give and take ensemble, whilst timbral contrasts are

genuinely refined. They characterise all three of the Eighth

sonata’s movements with real acumen, charting its moods and

paragraphs dextrously. There is nothing straight-laced about

the playing, and it’s not too rhythmically strict either. The

finale is notably vibrant and successful.

As for the Kreutzer, we find a consonant sense of the work’s

architecture and quixotic changeability. The opening movement

has plenty of propulsion but is neither over-vibrated by the

fiddle nor over-parted by the pianist. These are listening,

thoughtful performances indeed. A corollary is that certain

moments may be thought to be underplayed – take the opening

statements of the Kreutzer for example and also – despite the

fine sense of élan that comes with the unleashing of the first

variation in the central movement - certain moments subsequently.

This is a relative matter, of course, but I ought to note it.

They certainly do take a very relaxed view of the opening of

the Tenth sonata. It reinforces the intimacy they locate in

the works amidst the sense of dynamism. I happen to find this

movement rather devitalised, but acknowledge the consistency

of approach and can find nothing with which to argue in the

colouristic assurance of the same sonata’s finale. Similarly

there is a pleasurable articulacy in the opening of the Op.12

No.3 sonata – which is well balanced, naturally phrased and

not over-emoted. Braley proves a most able Beethovenian throughout

and an equal partner, and shows in the slow movement of this

E flat major sonata just how richly he can characterise.

So these are splendid, genuinely impressive performances. They’re

not stamped with the heroism of performers such as a number

of those cited above. They’re cut from a far more intimate cloth,

preferring incremental, dextrous playing. If your inclination

is for large scaled readings, then I suggest that these are

not for you. They exude a tenderness, and a relaxation, that

will appeal strongly to those who value chamber intimacies above

concertante vigour.

Jonathan Woolf

See also review by Michael

Cookson

|

|