|

|

|

alternatively

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

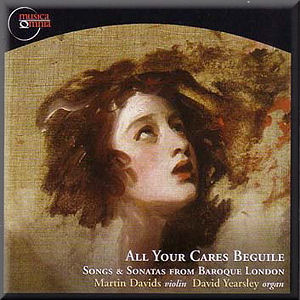

All Your Cares Beguile - Songs & Sonatas from Baroque London

George Frideric HANDEL (1685/1759)

Acis and Galatea (HWV 49): Sinfonia [3:03]

Henry PURCELL (1659-1695)

Music for a while (Z 583/2) [3:34]

Fantasia upon one note (Z 745) [3:06]

The Faery Queen (Z 629): Dance of the Chinese Man and Woman [4:12]

Nicola MATTEIS (?-after 1713)

Passagio rotto [2:43]

Fantasia [2:21]

Johann Christoph PEPUSCH (1667-1752)

Sonata in g minor, op. 2,12 [9:07]

Domenico SCARLATTI (1685-1757)

Sonata in G (K 22) [2:38]

Sonata in a minor (K 3) [3:49]

Sonata in d minor (K 18) [4:19]

Francesco Maria VERACINI (1690-1768)

Sonata in d minor, op. 2,12 [16:05]

Thomas Augustine ARNE (1710-1778)

The Tempest: Where the bee sucks [1:56]

George Frideric HANDEL

Giulio Cesare (HWV 17): V'adoro pupille [5:41]

Sonata in F (HWV 392) [12:44]

Martin Davids (violin), David Yearsley (organ)

Martin Davids (violin), David Yearsley (organ)

rec. 15-17 May 2006, Sage Chapel, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., USA. DDD

MUSICA OMNIA MO0111 [75:26]

MUSICA OMNIA MO0111 [75:26]

|

|

|

From the late 17th century onwards England, and especially London,

developed into one of the main centres of music in Europe. Musicians

from various countries settled there and looked around for employment.

Others just passed through, displaying their skills in public

concerts and then leaving again for another country. This disc

presents music by some composers whose music was performed in

"baroque London".

One of the first immigrants was Nicola Matteis, born in Naples

and entering England around 1670. He astonished audiences by

his virtuosity on the violin and published some books with pieces

for unaccompanied violin. These are expressions of his sometimes

bizarre imagination. Before the turn of the century Matteis's

example was followed by Johann Christoph Pepusch (not ‘Johann

Christian’ as the track-list says) who was from Prussia and

entered England in 1697. Here he developed into a respected

composer. His oeuvre has been overshadowed by his involvement

in the performance of John Gay's The Beggar's Opera in

which the Italian opera was ridiculed.

The success of this opera, first performed in 1728, contributed

to the troubles of George Frideric Handel, who settled in London

in 1712 and became the main composer of Italian operas. Until

the late 1720s he was very successful in this department. The

fact that he was also invited to compose music for royal and

state occasions bears witness to his dominant position in the

English music scene. His popularity also resulted in arrangements

of arias and instrumental pieces from his operas. His chamber

music was also much sought after.

Francesco Maria Veracini was one of those musicians who just

passed through in the 1730s. He was from Italy and travelled

through Europe as a performer on the violin. He wasn't only

known for his virtuosity, but also for his arrogance. Charles

Burney wrote that "Veracini was so foolishly vainglorious

as frequently to boast that there was but one God, and one Veracini".

This judgement didn't hold him back from acknowledging that

he was "the first, or at least one of the first, violinists

of Europe".

Domenico Scarlatti never visited England, but his music was

very popular there. Only one collection of sonatas for keyboard

was published in his lifetime, and it was not by chance that

it was printed in London. The three sonatas on the programme

are from this collection.

In addition to music by foreigners, pieces by two native English

composers are added. Henry Purcell was the most celebrated English

composer before the era of Handel, and his music was held in

high regard even in the early decades of the 18th century. In

some of his works Handel was clearly inspired by him. Thomas

Arne is the best-known English composer of the generation after

Handel. He had the bad luck to be overshadowed by immigrants,

first by Handel, and after his death by two other native Germans,

Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel. Even so, he considerably

contributed to the music for the theatre.

It is not that easy to give a fair judgement of this disc. From

which angle should one look at it? First of all, nearly the

whole programme consists of arrangements of some sort. Only

the two pieces by Matteis are played in the scoring intended

by the composer: violin without accompaniment. The three sonatas

by Scarlatti were written for harpsichord which doesn't exclude

a performance at the organ. The sonatas by Handel, Pepusch and

Veracini one is probably not inclined to call 'arrangements'.

The performance of the basso continuo in chamber music at the

organ is certainly an option, although it seems highly unlikely

that organs were used in public performances. Moreover, the

organ used here is more of the format of a modest church organ

than of an instrument used in private rooms where chamber music

was usually played. As David Yearsley is not afraid to explore

the full powers of the organ the basso continuo part is more

prominent than with a harpsichord or a positive. From that perspective

performances like on this disc can be considered 'arrangements'.

From an historical perspective there is nothing wrong with arrangements.

Handel frequently arranged music by colleagues, and his own

music was also often arranged by others. But if you are looking

for arrangements as they were in the time of the composer performances

of vocal pieces by Purcell, Handel and Arne with organ and violin

are not all that plausible. Whether the interpreters care about

this I don't know. David Yearsley ends his liner-notes thus:

"We make our arrangements of these songs and sonatas in

the tradition of opportunistic adaptation Handel so brilliantly

and unapologetically cultivated".

So let us say that these arrangements are partly unhistorical,

even if they are played with period instruments. The ultimate

question then is: do they work? The three sonatas by Scarlatti

work pretty well, although the second (K3) is not that convincing:

the repeated descending figure doesn't come off very well, and

can only be realised by using a slower tempo than would be ideal.

In the sonatas for violin and bc the organ is often too dominant.

But the performances as such also leave something to be desired.

The fast movements are mostly done well, although the andante

from Handel's ‘Sonata in F’ is played like an adagio. The slow

movements are generally too flat, with far too little dynamic

gradation.

The arrangements of the vocal pieces are quite odd, and I really

didn't like them. An opera aria with full-blown organ and a

violin is very strange. The short figures at the line "till

the snakes drop from her head" from Purcell's Music

for a while are very unnatural. The Fantasia upon one

note is even more curious: the 'one note' is played here

by the violin, with the organ performing the other parts. This

way the subject of this piece is singled out in a way the composer

obviously did not intend. An interesting question is whether

the mean-tone temperament which leads here to severe dissonants,

is in line with Purcell's intentions, even though this temperament

was common in Purcell's time.

Taking all things into consideration, I find this recording

not very helpful in painting a portrait of the multi-coloured

London music scene in the early 18th century. From a historical

perspective the performances are questionable, and musically

they are largely unsatisfying.

Johan van Veen

|

|