|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

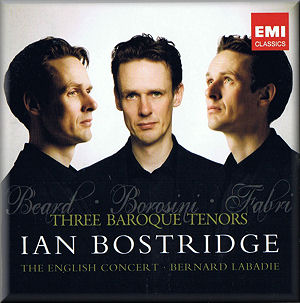

Three Baroque Tenors

Francesco CONTI (1681 – 1732)

Gui sto appeso (Don Chisciotte) [2.03]

George Frideric HANDEL (1685

– 1739)

Where congeal’d the northern streams (Hercules) [2.03]

From celestial seats descending

(Hercules) [5.57]

Antonio VIVALDI (1678 – 1741)

La tranna e avversa sorte (Arsilda) [5.25]

Francesco GASPARINI (1668 – 1727)

Forte e lieto (Il Bajazet) [4.09]

George Frideric HANDEL (1685

– 1739)

Forte e lieto (Tamerlano) [5.09]

Thomas ARNE (1710 – 1778)

Rise, Glory, Rise (Rosamond) [6.28]

Antonio CALDARA (1671 – 1736)

Lo so, lo so: con periglio (Joaz) [5.15]

D’un Barbaro scortese [3.26]

Alessandro SCARLATTI (1660 –

1725)

Se non qual vento [3.06]

George Frideric HANDEL (1685

– 1739)

Scorta siate a passi miei (Giulio Cesare) [4.06]

Antonio VIVALDI (1678 – 1741)

Ti stringo in quest’amplesso (L’Amenaide)

Saziero col morir mio (Ipermestra) [4.11]

William BOYCE (1711 – 1779)

Softly rise, O southern breeze [4.38] (1)

John GALLIARD (1666 – 1747)

With early horn (The Royal Chace) [4.44]

Ian Bostridge (tenor)

Ian Bostridge (tenor)

Sophie Danemen (soprano) (1); Madeleine Shaw (mezzo) (1); Benjamin

Hulett (tenor) (1); Jonathan Gunthorpe (baritone) (1)

The English Concert/Bernard Labadie

rec. 16-19 November 2009, 20-22 February 2010, Church of St. Jude

on the Hill, Hampstead, London

EMI CLASSICS 6268642 [66.39]

EMI CLASSICS 6268642 [66.39]

|

|

|

As a follow-up to his disc of Handel arias, Ian Bostridge has

come up with an anthology of music by Handel and his contemporaries.

It was all written for three star tenors who worked at various

times for Handel.

The trio featured on this disc, John Beard (1717-1791), Francesco

Borosini (1688-1750) Annibale Pio Fabri (1697 – 1760), all had

careers which encompassed the full range of the baroque stage.

We have a tendency nowadays to see them through the prism of

Handel’s operas. All sang for Handel, though Borosini and Fabri

did little more than a season each. But what seasons they were.

Handel wrote the roles of Bajazet in Tamerlano and Grimoaldo

in Rodelinda for Borosini, as well as converting the

role of Sesto in Giulio Cesare to a tenor by writing

new arias. Fabri, who came to London in 1724 some six years

after Borosini, performed Sesto, Goffredo in Rinaldo,

Grimoaldo and the title character in Scipione as well

as having roles written for him in Lotario, Partenope

and Poro.

It was Borosini who persuaded Handel to break the mould and

create such a strongly dramatic part as Bajazet, complete with

its on-stage death scene. Fabri did not inspire quite such revolutionary

roles, but his sheer ubiquity in major characters in the operas

Handel presented was revolutionary in its way. In having Borosini

and Fabri in significant roles in the operas, Handel was laying

the ground for the development of the tenor as main protagonist

instead of the castrato.

Beard was around for far longer; he was a member of the group

of English singers who were, in effect, trained by Handel. They

formed a strong part of his repertory company when he was tackling

oratorio. Though Beard did sing in Handel’s operas, it is for

his oratorio roles that he is known. His powers were such that

Handel again broke the mould and created such parts as Samson

for him. But Beard was a full-time theatre professional and

acted as well as sang. The pieces written for him which Bostridge

performs on this disc include arias by Arne and Boyce.

Beard’s signature tune was the wonderful, With early Horn

from John Galliard’s The Royal Chace, a lovely piece

of musical hunting extravaganza. No less delightful is Rise,

Glory rise from Arne’s Rosamond. But the most memorable

of the non-Handelian roles showcased here is the lovely aria

from Boyce’s serenata Solomon. It has an extremely expressive

independent bassoon part, and a concluding section which includes

a vocal quartet.

Of the many parts Handel wrote for Beard, Bostridge has included

two arias from Hercules, where Beard sang Hylluss. This

offers lovely lyric writing - from earlier in Beard’s career

- rather than the more dramatic Samson.

Whereas Beard was trained by Handel, Fabri had a very conservative

training with a castrato. He was well versed in all of the bel

canto practices for which castrati were famous. It is Fabri’s

arias on this disc which perhaps take the most traditional trajectory.

His talents were early exploited by Vivaldi. The arias from

L’Atenaide and Ipermestra display Vivaldi’s talent

for writing attractive, often toe-tapping music. That said,

you never feel that he gets to the nub of a character the way

Handel could. In the aria from Scarlatti’s Marco Attilio

Regolo, Fabri would have got to show off his agility in

delightful manner, though the music does rather skim over any

characterisation.

Francesco Borosini by contrast had a voice which was positively

baritonal in texture, but covered both the tenor and baritone

ranges. However it was the intensity of his acting, and presumably

the strength of his personality, which persuaded composers to

break with tradition. The opening track on the disc is from

a tragi-comic opera Don Chischiotte by Conti, which features

the Don hanging awkwardly by one arm from a window whilst singing

this aria! It’s a delight and makes me wonder what the rest

of the opera is like. Bostridge features just one role which

Handel wrote for Fabri, Alessandro in Poro. Alessandro

is almost the major character in the opera and the aria, D’un

Barbaro scortese is demanding and must have shown Fabri

off to his best. Note that though Alessandro is the major character,

he is not the love interest.

In 1719 Borosini managed to persuade Gasparini to write a significant

role for him in Il Bajazet. In doing this he created

the first ever major on-stage death scene in baroque opera while

also giving Borosini a chance to shine both histrionically and

musically. When he came to London he brought the score with

him. Handel was sufficiently impressed with Borosini’s talents

to perform a similar task on his unfinished Tamerlano and

thus give us Bajazet’s on-stage death scene. Bostridge has recorded

here the same aria from both Gasparini’s and Handel’s operas,

Forte e lieto. The comparison of the two displays the

difference between talent and genius as it is Handel who manages

fully to articulate the tragic figure of Bajazet.

When Handel decided to re-write Sesto for tenor he added new

arias, rather than simply transposing the existing ones down.

The results emphasise the transposition of the role from youth

to man. Scorta siate a passi miei, with its leaps and

angularities of line, displays this admirably. I remain puzzled

as to why no-one has experimented with performing Giulio

Cesare with Sesto as a tenor; the arias Handel wrote just

cry out to be performed in context.

Perhaps because much of the material is less familiar, I found

that Bostridge was rather less mannered than on his earlier

Handel disc. It is a relief to find him singing material written

for the tenor voice, rather than appropriating arias from other

voice types. You get the feeling that the three baroque tenors

featured here had rather more dramatic voices, in the line of

Thomas Randle, Mark Padmore or John Mark Ainsley. Bostridge

is a lyric tenor and though he sings with great intelligence,

there is no disguising that some of the music is less than ideal

for his voice. That said, he is never less than admirable and

brings his customary intelligence to everything he does.

Labadie and the English Concert provide strong support and there

is some attractive solo playing.

I could wish that the CD booklet had been produced with a little

more care. Nowhere in the track-listings do they tell you which

aria was written for which tenor. To find that out you have

to go through the booklet article with a tooth-comb. Also, when

Bostridge sang in concert at the Barbican as part of the tour

to promote this disc, the programme note reprinted an extremely

informative article by Bostridge himself, which had appeared

in the Guardian. For some reason, this has not been reprinted

here, which is a shame as Bostridge is as articulate in print

as he is when singing.

There is no denying that not everything on this disc is music

of the first water. Sometimes it descends into generic baroque

knitting - something Handel was as capable of as anyone. But

the point of the disc is to explore the range of music written

for these three tenors and as such it works admirably.

Robert Hugill

|

|